By Ozge Suvari

At the end of 2024, our team—Esra, Kelsea, Fatima, Jennifer, Kyra, and I—attended the SRHE International Conference in Nottingham, UK. Organised by the Society for Research into Higher Education (SRHE), this three-day annual event brings together researchers and educators to advance understanding of higher education through insightful discussions, knowledge exchange, and presentations. This year’s theme, “Higher Education: A Place for Activism and Resistance?” set the stage for a vibrant exchange of ideas, and we were excited to contribute by presenting our research.

Professor Jan McArthur delivered the opening plenary, focusing on the challenges of navigating a shrinking world of higher education and the balance between hope, resistance, and pessimism in this context. She highlighted an important point: a degree of pessimism is an inherent part of pursuing social justice in higher education. In this shrinking world, budget cuts and deficits are not the only challenges; the politics of citation also play a critical role for researchers engaging in resistance through their work. She presented co-citation analysis diagrams in higher education research, illustrating how consistently citing “seminal authors” can inadvertently perpetuate the very injustices we aim to challenge. The fact that most first authors are based in the Global North was a striking example of how our knowledge production is Western-centric.

The parallel sessions following the plenary made this topic even more interesting. Mark Skopec, presenting on behalf of his team at Imperial College London, shared a striking map illustrating the global imbalance in research consumption. His presentation focused on an automated reading list analysis tool that visualises the countries of authors cited in reading lists, aiming to support discussions on representation in curricula. It was fascinating to see how decolonisation efforts in STEMM institutions take diverse forms and how data-driven methodologies, such as theirs, can be applied.

On the second day of the conference, one of the plenary speakers, Dr Laila Kadiwal from UCL, delivered a thought-provoking talk on navigating academic freedom, neocolonialism, and Islamophobia in UK higher education. She shared her lived experience of encountering academics who dismissed the significance of madrasahs as educational institutions. In an interactive moment, she asked if anyone was familiar with Ibn Sina (known in the West as Avicenna), and only a few attendees recognised the name. Her talk deeply resonated with me; as someone educated in non-Western institutions, I often find myself assuming that my prior degrees and knowledge of the non-Western world hold less value or relevance in this context. However, she stressed that becoming anti-racist in higher education requires addressing these struggles, challenging our own biases, and recognising that history is not fixed but open to reinterpretation. Her emphasis on examining the colonial foundations of our institutions was both powerful and necessary.

Acknowledging diverse centres of knowledge production was another key theme, particularly in a symposium on doctoral education on the third day. Presentations on decentring, decolonising, and relational doctoral pedagogies, mainly focusing on international students, were particularly engaging. Professor David Hyatt’s presentation stood out to me. He emphasised the importance of recognising the first academies in China, Buddhist monasteries in Northern India, the Academy of Athens, and the scholarly madrasahs of the Islamic Golden Age alongside medieval European universities. He asserted that decolonising doctoral education and knowledge production requires re-narrating both institutional histories and presents, reflecting the insights shared by Dr Laila Kadiwal during the plenary session on the conference’s second day.

In the same symposium, Dr. Kay Guccione presented her research from The Lab for Academic Culture at the University of Glasgow, focusing on expanded doctoral pedagogies and the often-overlooked informal and accidental learning that shapes academic experiences. Her emphasis on the agents of the hidden curriculum, such as English language specialists and research librarians, showed the diverse environments and individuals that contribute to meaningful learning. Another notable presentation I listened to at the conference explored the Close the Gap project, which aims to reduce the Offer Gap for UK-domiciled applicants from underrepresented ethnic groups at Oxford and Cambridge. Due to my own positionality as a PhD student, I deliberately choose sessions on doctoral education and pedagogy, but I have also seen that decolonising knowledge production and research is closely tied to doctoral education. These discussions reinforced my understanding of how decolonial theory can inform education at all levels.

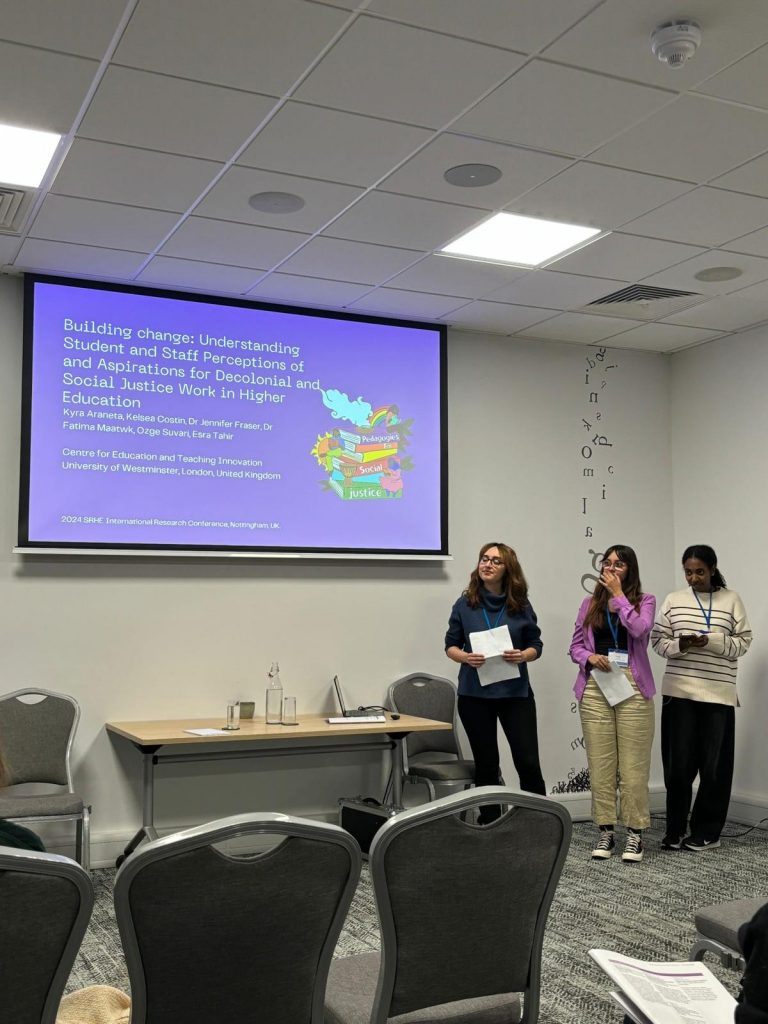

As part of the conference, Kelsea, Esra, and I presented our collective research with Kyra, Fatima, and Jennifer titled “Building Change: Understanding Student and Staff Perceptions of and Aspirations for Decolonial and Social Justice Work in Higher Education.” The presentation was about the survey results on decolonising the curriculum and the importance of decolonial relationality and relationships. We had amazing reactions from the audience; people responded to our questions as well as asked us questions. Rather than criticising our ideas, they expressed curiosity about learning more about the Student Partnership and Pedagogies for Social Justice (PSJ) project. I felt that students taking up space and talking on their behalf had significant power and impact.

This year’s theme aims to explore how students and staff are involved in various forms of activism, yet I noticed a surprising lack of student representation, at least in the sessions I attended. Many presentations acknowledged that contributors from the Global South could not participate due to funding or visa barriers. This draws attention to accessibility issues and barriers to participation, which feels particularly ironic given the conference’s focus on decolonisation and academic freedom. Conferences often feature the most cited senior academics from prestigious institutions while providing limited opportunities for other academics and students to share their perspectives. This raises important questions: are conferences safe and equitable spaces for students in the first place? If not, how can we ensure they become so? When we talk about academic freedom, for example, whose freedom do we prioritise over others, or do we only want freedom for ourselves? I believe these questions are strong reminders that there is still much to change and dream about university.

Ultimately, this conference left me with many questions, which are essential for grappling with the pessimism often inherent in social justice work. But I also left very hopeful and uplifted, probably because of the privilege of spending time with our team and connecting with other researchers with similar concerns. Witnessing the diversity of research projects and teams broadened my perspective on the complexity of social justice work in higher education, from attainment gaps, doctoral education, and research to histories and geographic centres of knowledge. I left the conference believing that creating spaces to discuss social justice, decolonisation, and activism is self-transforming. But most importantly, I left thinking that being anti-racist and anti-colonial is becoming ever more necessary for higher education.

- Reflections on Pedagogy of the Oppressed (Chapter 1) - 17 February 2025

- Education As a Site of Creative Liberation - 17 February 2025

- Reflection on Pedagogy of the Oppressed and Westminster’s Student Partnership Framework - 17 February 2025