Reimagining the curriculum as a circular economy

Andy Pitchford

Head of CETI

27 March 2025

One of the more depressing moments of my academic career was on a July Friday, in the midst of a long, hot summer sometime in the late 1990s.

I had just taken the wrong door out of my department office, having had a very nice chat with the people there which had distracted me somewhat from my morning’s journey. I found myself, blinking like an amateur Mr Benn, in a new and slightly disturbing environment – a dark, foreboding extended cupboard which had become known to all those brave enough to enter as ‘The Marking Room’.

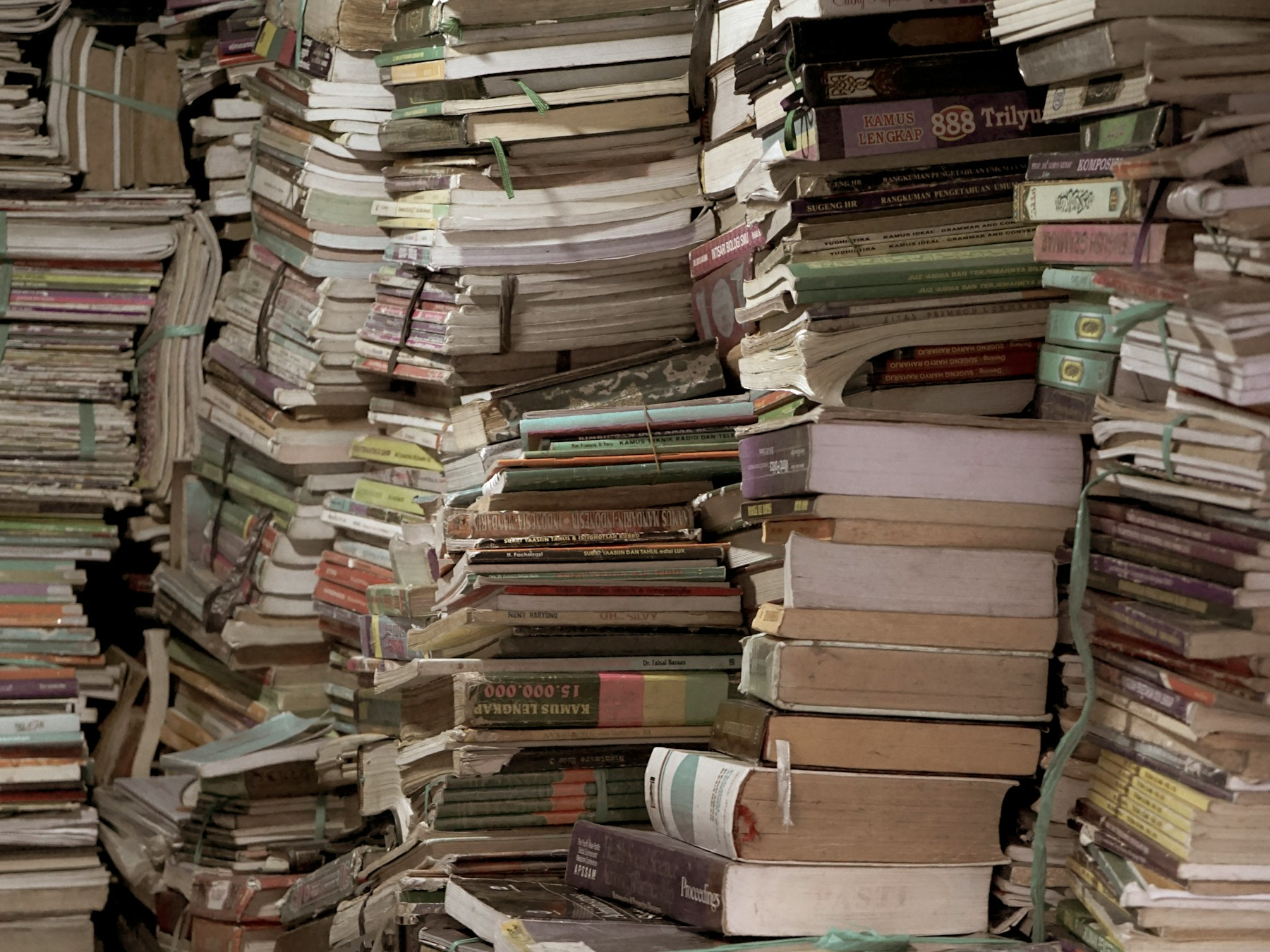

Here were piles and piles of exam scripts, stacked up floor to ceiling, alongside hundreds of assignments slithering around in their plastic sheaths. Battered, bent-eared posters jostling for space with chunky portfolios in squeaky ring binders. Alongside stood the highest pile of all, the imitation-leather heat-bound dissertations with their gold embossed titles. Years and years’ worth of the work of both colleagues and students, crammed into a chamber for the Quality Gods, the gifts of assessment laid ready to appease the highest of authorities. And there, tucked away in the corner, was my contribution to the tribute. A collection of essays, set annually with great care and attention, representing what I considered to be the very best of my field, topics likely to simultaneously challenge and inspire the learners on my course. Attached to the front of each essay was some carefully worded, thoughtful and thorough feedback. I flicked through some examples and there was some great work – sometimes it was the students; sometimes it was me. I congratulated myself on some incisive observations and laconic wit. There were some occasions where both the student and I had performed well, an affirmation of staff student partnership and a celebration of higher learning. Well done to us all, I remember thinking.

Then the horror struck me. Most of the work in this room was actually for return to students, not fodder for the university archive. But there were thousands of pieces here that were simply detritus. Nobody wanted them, they were of no value. Years had passed and their producers had forgotten them. Worse still, the biggest pile of wasted effort was mine. The hours I spent on that feedback – the hours! My frustration wasn’t with the students, but with our system. All of those ideas, those words and sentences, those images. All of the knowledge constructed, and all of it read by a single person, perhaps with a tiny bit of help from a second marker. The physical waste was one thing – the paper and the plastic and the staples – but the waste of all the ideas and imaginative enterprise was much more galling.

Now for the curriculum

I’m often reminded of this moment when we talk about sustainability and the general principles of trying to avoid waste, particularly when I hear others talk about circular economies. It’s easy to sympathise with the aspiration to organise markets and exchange in a way that minimises waste and encourages the continual renewal of materials, but I wonder if some of the same principles could be applied to the way in which we design and deliver assessments – in other words the ways in which students construct knowledge and its artefacts and outputs? Could we rethink the operating system that dominates our education, and unpick some of the linear thinking that is such a feature of our experience? Is there potential to build on the work of other scholars, rather than engage in an annual cycle of producing from scratch? Can we engage in longer term thinking that takes us beyond the confines of a module or a semester? What might a cyclical model of knowledge construction look like in a university, where we imagined the curriculum as an eco-system rather than the boxed-up, stage-by-stage journey with which we are so familiar?

It might be that some colleagues are already directly promoting this kind of thinking through engagement with emerging circular economies. The amazing Cavendish Living Lab and our new partnership with Hazaar being two really obvious examples. But more generally, a feature of authentic learning is the notion that it creates benefits for other stakeholders beyond the classroom, so when learners construct knowledge they are doing so with another recipient in mind. These recipients could be other members of the university, staff or students, or local communities or neighbourhoods, local charities or enterprises or more established corporate partners. Creating these connections will often be motivational for students, giving them a sense of purpose and agency that might be lacking with more abstract exercises. They also carry with them the possibility that their ideas might be adopted or put into practice in some way, with the associated benefits for the confidence and self-efficacy of the learners.

At Westminster we have some long-established examples of these attempts to challenge take-make-and-dispose learning. Students in our Legal Clinic produce reports to guide members of local communities on their interaction with the law; Architecture students design and build actual structures through Live Projects and offer guidance to external stakeholders on a myriad of issues through the Live Practice Studio. Client briefs in the Business School encourage students to imagine solutions to the challenges faced by our alumni or local enterprises; and our Art and Fashion students are continually producing outstanding work for wider consumption.

Yet there is potential for so much more. We could, for example, start to think about the benefits of communicating the knowledge in our discipline to other communities more thoughtfully and deliberately. Educating other university communities about art, history, decolonisation or nutrition might stimulate new interests or debates. Perhaps learners from some fields, such as Human Resources or Enterprise, might play a part in the employability journey of other students? Then there are the vertical possibilities, could students at nominally higher levels create materials or resources or events that help their peers at earlier stages to learn?

More fundamentally, does our engagement with agencies such as Citizens UK, give us the opportunity to do more listening with communities within and beyond the university walls? And could we respond to these listening campaigns with new interventions, products or creations? Rather than impose our understanding on others, we might begin a circular process where we listen to community need and then attempt to address it through the knowledge we create.

Conclusion

We are, of course, living in a different world now to the one I experienced that summer in the Marking Room. There are no longer so many physical rooms with work piled up, now our Rubbish Tip is somewhere in the Cloud. But we are still wasting the work of our students, when so much of it could be put to good use, with our students more obviously seeing the relevance and reward for their endeavours.

Image: Carles Rabada via UnSplash

About the Author

Andy is the Head of the Centre for Education and Teaching Innovation at the University of Westminster. He has led community engagement initiatives in universities for the past 30 years and was awarded an Advance HE National Teaching Fellowship in 2015 in recognition of this work. With David Owen and Ed Stevens, he published the Handbook of Authentic Learning with Routledge in 2021.

- Westminster students reimagine university welcome experience in CETI project - September 26, 2025

- Celebrating Multilingualism at Westminster - September 26, 2025

- Enhancing student group work - April 30, 2025

Leave A Comment