Is London losing its Palimpsest Character?

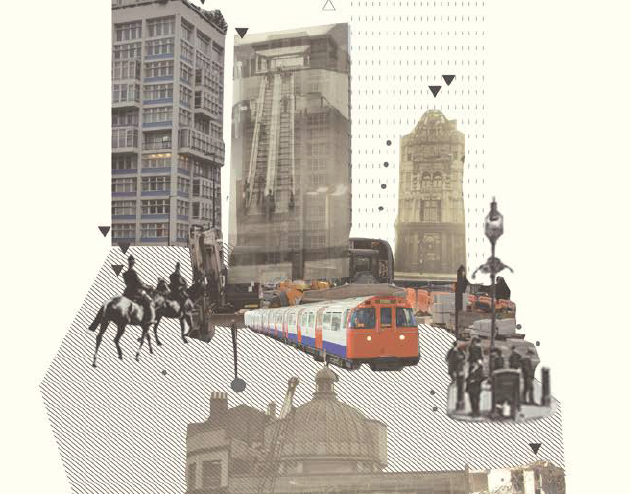

London is a living organism [Fig.1] constantly changing. By the mid-twentieth century the city started facing dramatic transitions. Firstly, The Second War World burst into the social fabric, deteriorating collective networks, thus affecting the conception of urbanity itself (Porter, 2000). Economic, social and cultural problems from that time are still visible nowadays, particularly in South London, where social and spatial fragmentations contribute to the appearance of new social boundaries within the inner city; one of them is the aggressive urban transformation that does not allow the community to digest the changes and push them far away from the city centre (Hayden, 1995). Secondly, in 1947 the British Empire started to fade out principally due to the Indian independence. And thirdly, to reinforce that shifting cycle “The death of the Docks” (Porter,2000. p425) took place in 1970’s, when many of the factories around Docklands [East London] were closed. However, London was not going to become a loser, so the ‘London Dockland Development Corporation‘ was created in order to revitalize the area.

That process is partly responsible for all the dynamics of redevelopment that are taking place in London, it detonated and spread out all over the city the non-stoppable impetus for regeneration,transforming “derelict and no desirable spaces” into clean places where the “Urban Renaissance” validates London -and its government- as a Millenial and global city (Campkin, 2013). As a consequence, inner London communities started facing the polarization of certain areas “huge estates of poorer working-class and immigrant council tenants and, on the other hand, affluent owner-occupier” (Porter, 2000. p429). Consequently, the whole process of urban regeneration is indeed a process of displacement and economic interests. Furthermore after 1980, within Thatcher’s government1 economic policies on regenerative power “created Nouveau Riches in the city and in certain fields of enterprise. Yuppies helped to generate a property boom in gentrifying districts, employment grew in boutiques, restaurants, car showrooms and other forms of domestic and conspicuous consumption” (Ibid, p463).

Furthermore after 1980, within Thatcher’s government1 economic policies on regenerative power “created Nouveau Riches in the city and in certain fields of enterprise. Yuppies helped to generate a property boom in gentrifying districts, employment grew in boutiques, restaurants, car showrooms and other forms of domestic and conspicuous consumption” (Ibid, p463).

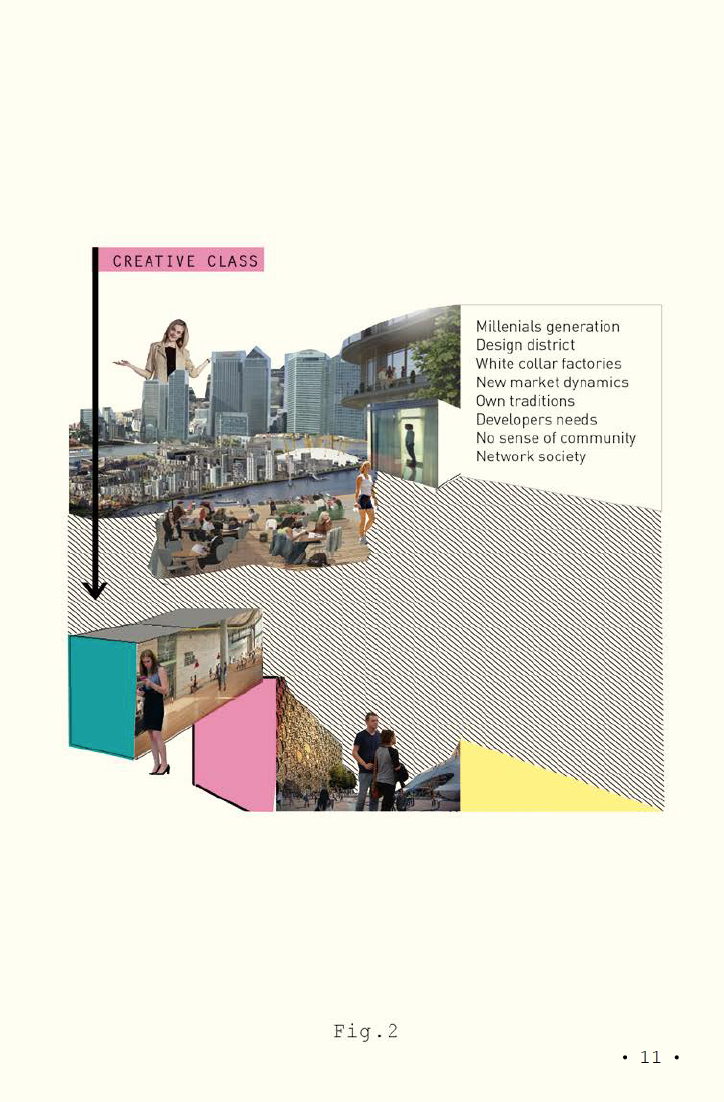

By the turn of Twenty-First century, the new generation of so-called Millenials appeared [Fig.2]2 demanding a place in the city. Consequently, fragmentation inside local traditions and social practices increased community displacements and gentrification (Minton, 2006). The big social issues of the Century. In cities such as London and New York the forces of redevelopment have been absorbing the identity of small and local services that gives its character to city’s neighbourhoods, particularly those with Ethnic Minority populations (Zukin, 2010).

Evidently, these regeneration processes are taking place in derelict and non-desirable spaces in the city; where ethnic minority groups meet (Román, 2016), that is to say inhabitants that have a shared origin background. An example3 of this is Elephant and Castle [E&C], where the feeling of ethnicity is frequently fixed in association with Latin America (McIlwaine, 2011). Moreover, the relationship between ethnic groups and urban spaces overlaps almost every sphere of the city’s definition. “Founded by immigrants, London has had a ceaseless history of immigration” (Porter 2000, p435). This is the city of no-one and everyone, as the majority of the forces -political, economic and social- that runs the city are out of the rich of the population itself, the experience of the city is shifting the urban place into a soulless space where people are not able to own and identify their selfs with the site as it is always changing in regards to the economic forces that stands upon the identity of social groups that inhabits the urban village, as Zukin mentioned “the physical fabric of the city is constantly changing around them -residents-” (Zukin,2010. p21) in that order the city is losing its authenticity in terms of the loss of cultural rights for the long time inhabitants, a lost of the dynamics of communities that live and work in the same social frame. Gentrification is the sickness of the global city because it disturbs the desire of remain and retains cultural differences, instead, it promotes “ dense crowds where no-one knows your name, high prices for inferior living conditions, and intense competition to be in style” (Ibid). That is what the author called “Manhattanization”, which is no far from what is happening in London, where the immigrants and ethnic minority background communities that were rooted in traditional neighbourhoods and are disappearing or being displaced, due to the lack of awareness of government and the new inhabitants of the neighborhoods, in regards to the local atmosphere and the lack of connection with the space itself, which affects the conception of city culture. A sense of community is getting lost in the habits of London as a universal city.

The British capital sells itself as a welcoming place where everyone is invited, although since 1960’s new migrant’s laws had been introduced in order to control and regulate who enter the country, configuring how the city itself is experience and transform into a place (Cock, 2010). For all the reasons explain above this essay will consider the discourse of social diverse groups as the tool to analyze communities and the urban realm, focusing in the Latin American community of South London.

London as a Palimpsest

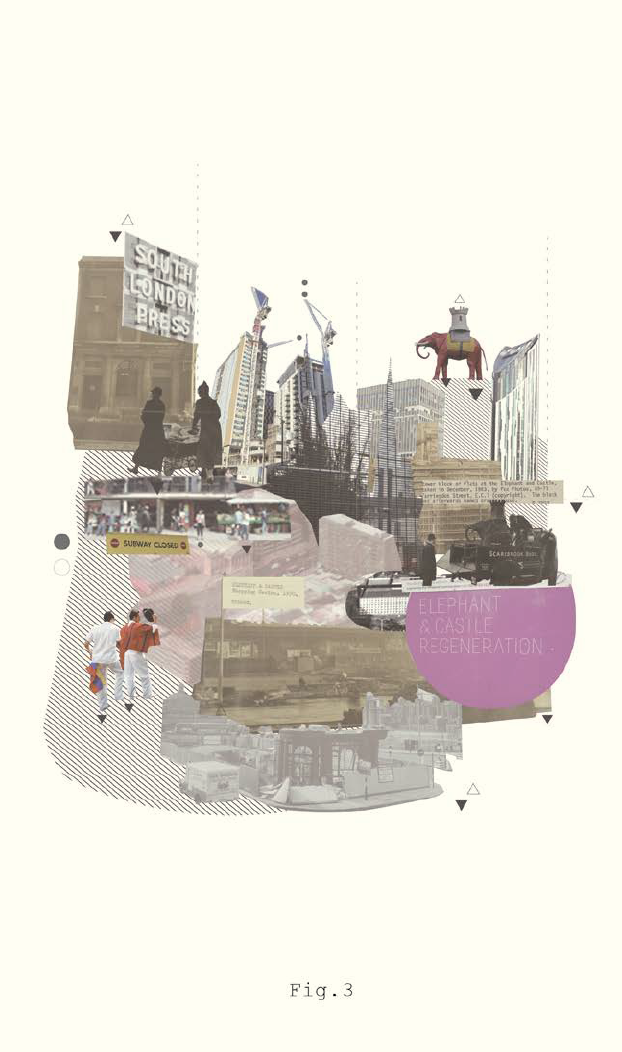

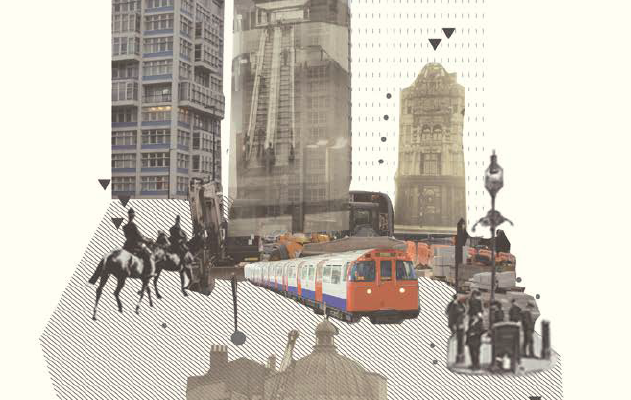

Evidently London has many layers of history circumscribed4, which can be related to the Linguist concept of palimpsest [Fig.3] in social and urban spheres, allowing one to reinforce the idea of intertwined meaning. As Andreas Huyssen describes the concept5, “Palimpsest implies voids, illegibility, and erasures, but it also offers a richness of traces and memories, restorations and new constructions that will mark the city as lived space” (2003, p84). Although Huyssen’s use of the concept is more related to the urban space as place that contains layers of memory, it can be argued that communities also nourish those memory-spaces and its social character is as well intrinsic in the layers, building the whole concept of urban the palimpsest.

The sociologist Godfried Engbersen uses the palimpsest metaphor to develop the concept of urban marginality in terms of the official and the unofficial citizens -legality and illegality- in the contemporary construction of the urban fabric. As the author stands “ the palimpsest metaphor is applicable.

There exists an ‘overworld’ of formal rules and objectives and an ‘underworld’ of informal rules and adjusted objectives, and sometimes even of illegal practices. The forms and processes of urban marginality and policy described here reveal border crossings, connections, and linkages between a formal overworld and an informal underworld. This interwovenness can find expression in a person, but also in a company, branch of industry, household, a public institution, community or limited urban space”. (Engbersen, 2011. p8). Therefore the concept is fundamental in order to understand the dualism of cities, such as London, that divides its citizens between immigrants and non-migrants, leading to whole discourse and analysis of different diasporas that localize themselves together geographically within the urban realm.

This argument is also related with the work of the artist Edgar GuzmanRuiz, who has been working with the Palimpsest concept as a way to explain the myth of Germania and the Holocaust horror in Berlin and how it affects many generations after that in the way they conceive the city and the public space. As well as Huyssen, GuzmanRuiz uses the metaphor to create a reflection about memory and the urban fabric. Whereas Engbersen recognises the importance of the geographical and social realms its development of the concept is based on a description of contemporary society in terms of urban marginality, that is to say, discrimination of the jobless and immigrants. Bearing these definitions in mind I will address how a community (Latin Americans) that is recognized for being foreigners and outsiders developed and create a space that has its own roots and social dynamics between the legality and illegality. Additionally, I will address how the process of London city development scheme is trying vanish or change their cultural practices within the British environment, in that sense the urban palimpsest character that identifies transcultural societies (Asante2001), such as London, is in risk of being homogenised into just one layer.

In this work, I will be examining the situation that has been taking place in Elephant and Castle. Under this scope, the essay will be addressing the notions of London as a City that overlaps layers of meaning tending to ignore some of them in order to give more voice to a desire for profit within the contemporary economic system (Minton, 2006). By doing so, I will be looking at a brief description of the historical re-development processes in the area in order to do a critical analysis of the process nowadays. A key point is the definition of urban landscape by Dolores Hayden as an “urban design that recognizes a social diversity of the city as well as the communal uses of space, very different from urban design as monumental architecture governed by form or driven by real estate speculation”(1995,p12). I will be criticizing the undergoing desire of the developers6 and Southwark Council for a new South London, based on Richard Sennett complexity definition within the urban realm as the way to create permeable spaces allowing inhabitants and visitors to “engage more with their surroundings” (2009, p225). In addition, illustrations and photographs will be depicting the concepts, within the notion of Fading Layers, addressing the question about whether London is losing its palimpsest character and erasing traces from places that are facing a metamorphosis. Finally, some of the contemporary process for Latin American community ‘inclusion’ will be shown in the light of Anna Minton’s analysis of the privatization of public space (2006) as a conclusion to tackle the revitalisation allowing questions to emerge about what will happen in E&C with the community.

Contextualisation

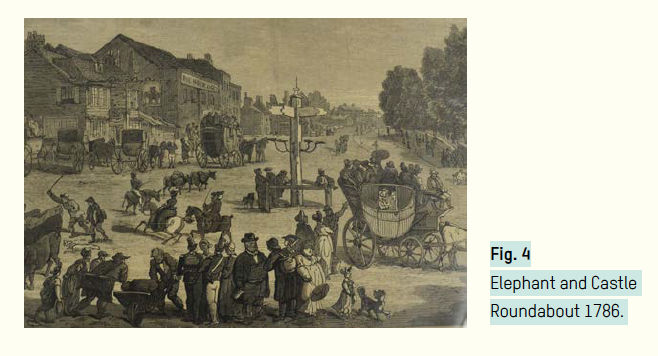

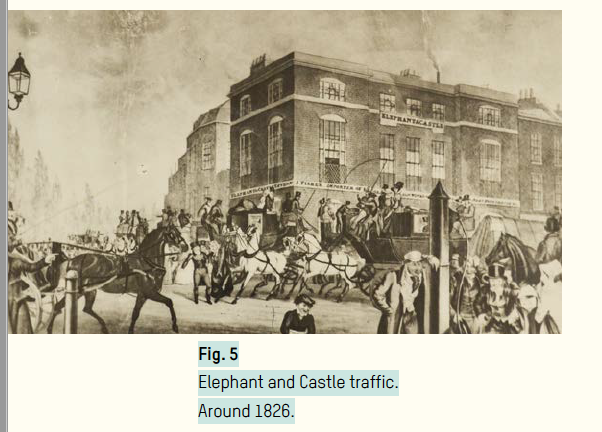

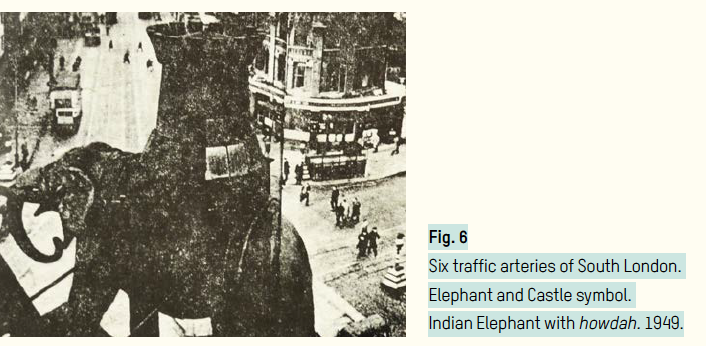

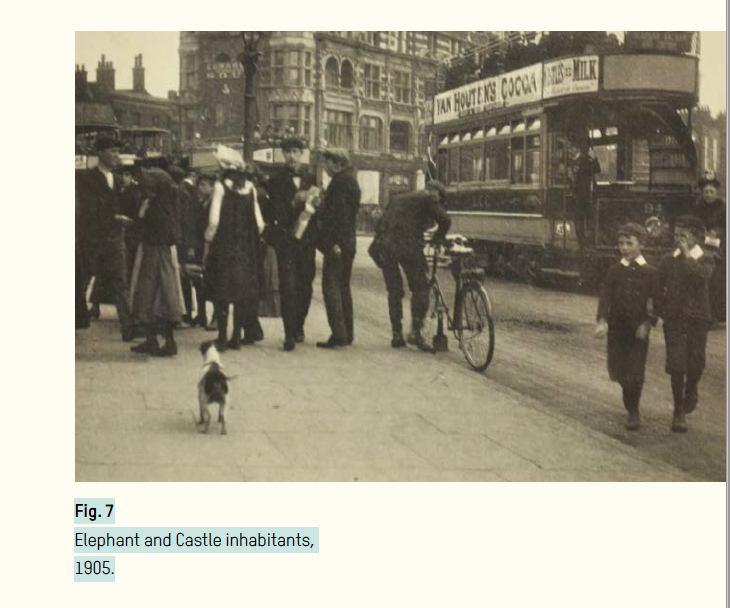

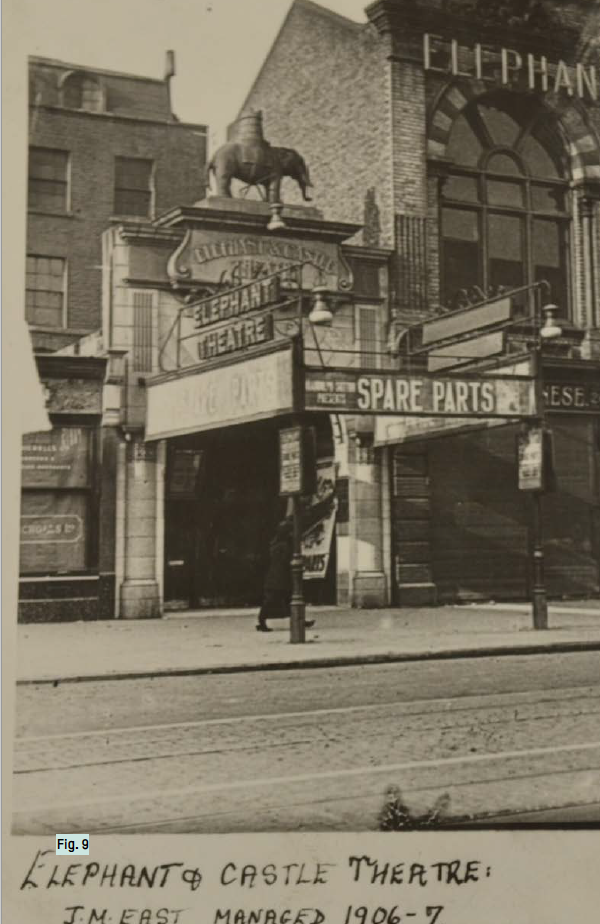

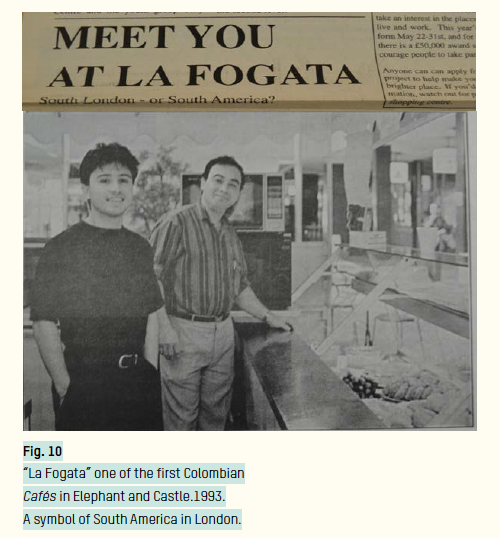

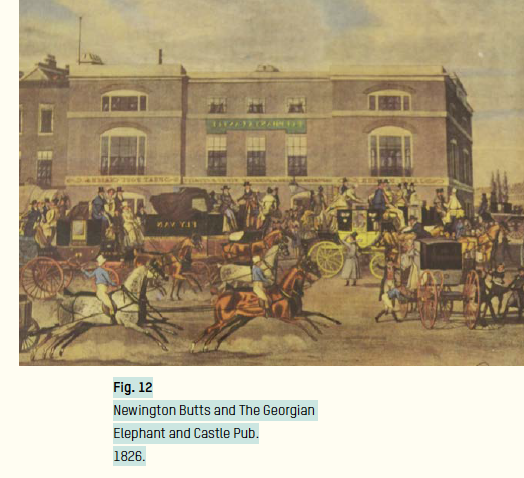

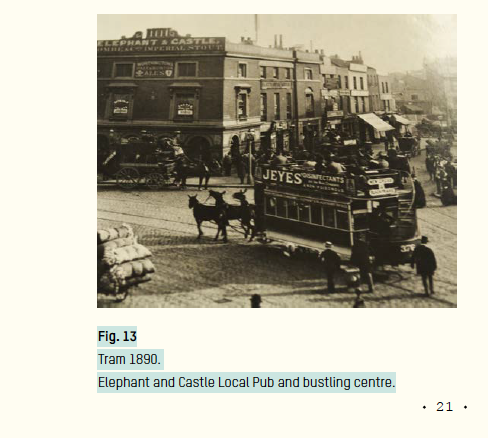

The Elephant and castle area was known as the “Picadilly Circus of South London” (Humphrey, 2013, p5). The area took its name from a public house, around 1765. Elephant and Castle was a hub for social interactions, a busy roundabout full of horses,[Fig.4 and 5] cars, buses [Fig.6 and 7], shops founded by local entrepreneurs [Fig.8] and leisure centers [Fig.9]. However, the essence of the place was and still is its people and the social environment [Fig.10].

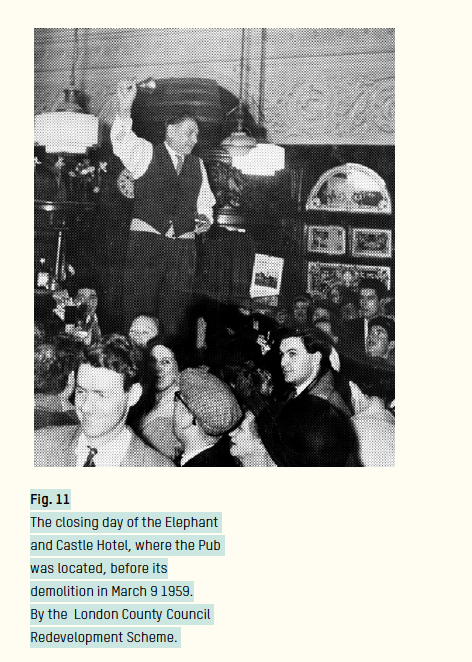

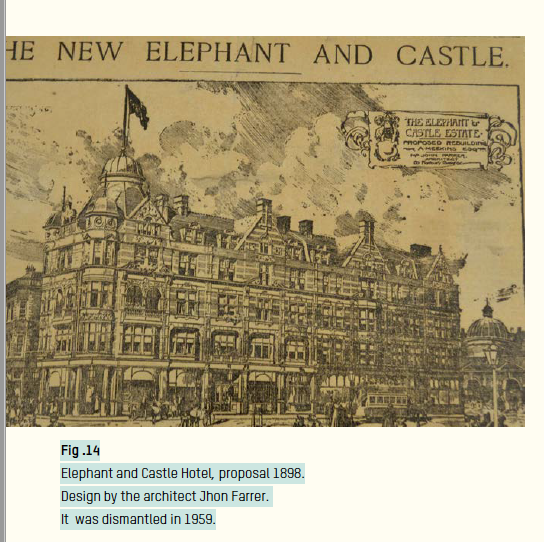

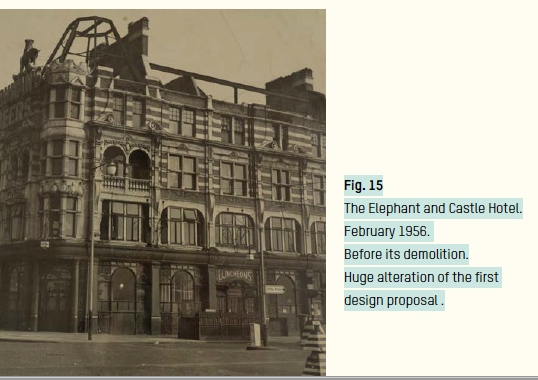

The Palimpsest character of E&C is represented by the restructuring process that has been circulating the area over the last 200 years, as an example the local pub7 that was reconstructed in more than one occasion [Fig.11, 12,13, 14 and 15]8 .

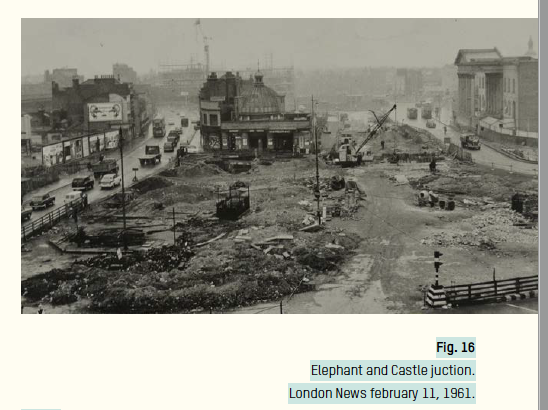

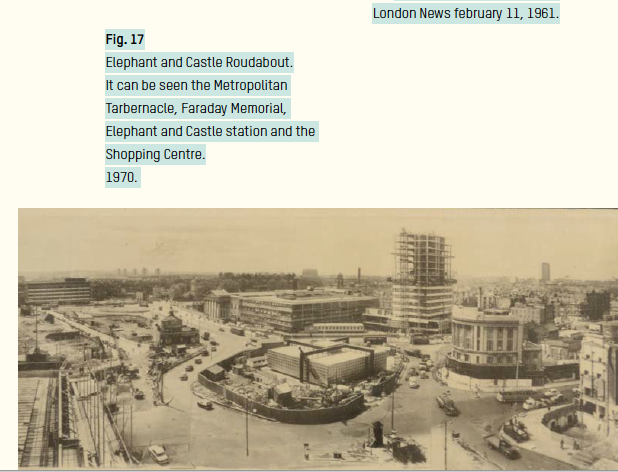

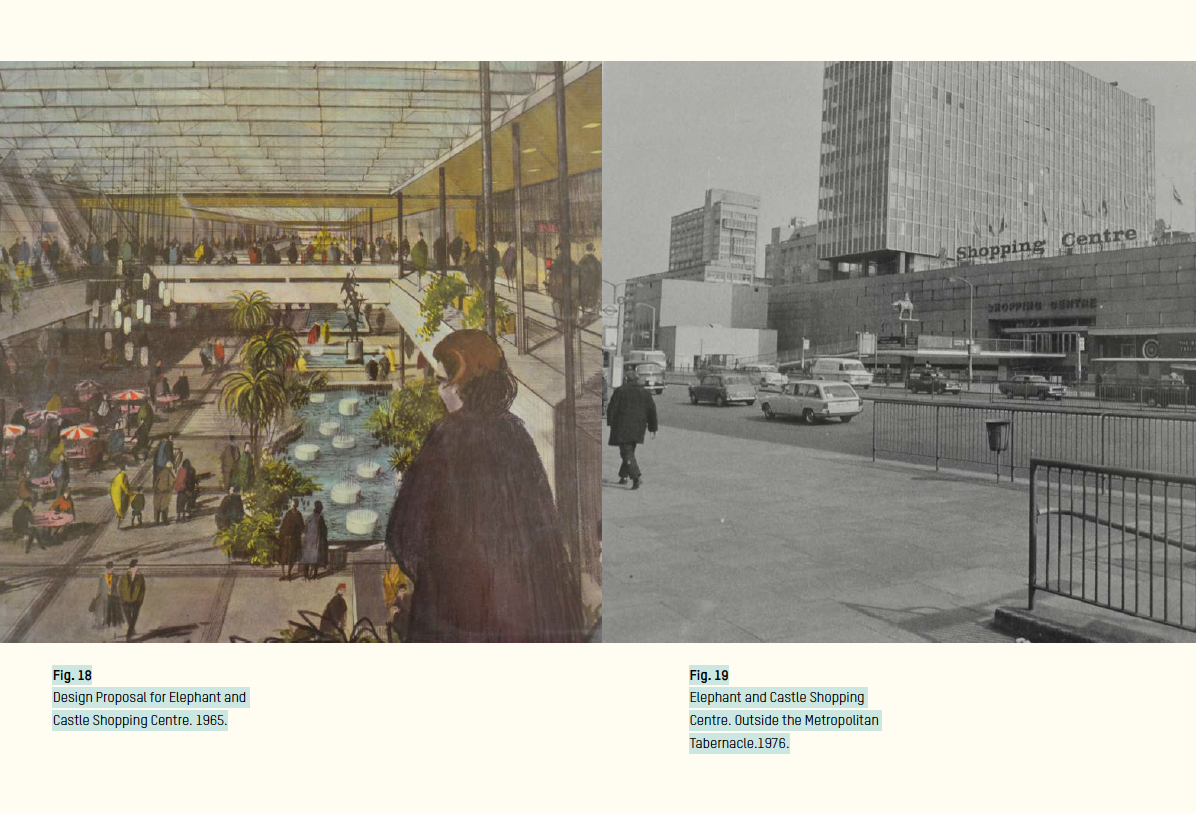

The blitz left south London full of rubble and wreckage [Fig.16 and 17]9. So that, in 1960’s the construction of the Elephant and Castle Shopping Centre aimed to revitalise the area and give South Londoners a new space for social interactions [Fig. 18 and 19].

The shopping Centre and the Latin American Community

From the 1960’s until 1990’s, Latin America was struggling with social political and economic problems10 which left the continent with a massive number of disappearances, kidnapping and forced displacement. During Thatcher’s first government the UK welcomed Chilean and Argentinian exiles, from that time many Latin Americans started to migrate to the UK as a way to start new life. In the 1990’s Colombian, Ecuadorian and Venezuelan’s communities started to grow in the capital and by the turn of the Twenty First century there were already large communities of Latin Americans established in London (Mcllwaine and Cock, 2011, p13).

From the 1980’s onwards the selling of London to the “international super-rich” (Porter, 2000, p467) increased the development of touristic spots in the city, which brought new jobs for migrants and second-generation migrants, hence developed many polarized areas11.

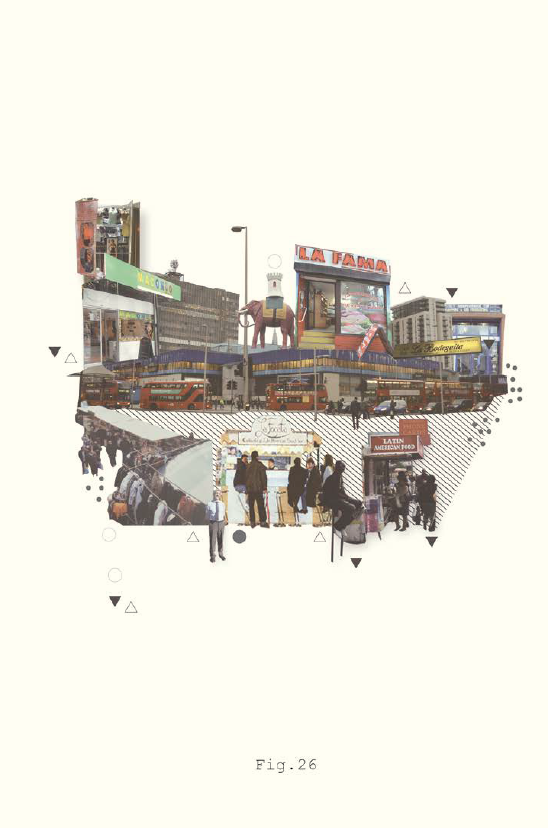

One of those polarized spots is the Elephant and Castle Shopping Centre and its surroundings12. Although this place is a commercial space it is really particular how it has shifted into a social place. It is a meeting point inhabited by the Latin entrepreneurs that arrived in London from 1970’s until now. ”What marks them13 as ‘Latin Americans’ is the agglomeration of commercial spaces owned by and aimed at Latin American migrants as well as the recurrent use of local public and community spaces for gathering and faith meetings” (Cock,2011, p180). The place is a faithful representation of Transculturality, “It intends a culture and society whose pragmatic feats exist not in delimitation, but in the ability to link and undergo transition. In meeting with other life-forms there are always not only divergences but opportunities to link up…” (Welsch, 1999, p6). The concept of transculturality was first define by the Cuban Sociologist Fernando Ortiz back in the 1940´s to describe the mix of the African slaves, spanish and native people from Cuba. Ortiz mentioned how important is to merge and mix in order to allow new cultural dynamics to appear in the new space that diasporic communities inhabit. (1940). Elephant and Castle shopping centre is a space where diverse social groups crossed cultural boundaries and becoming part of London’s urban culture.

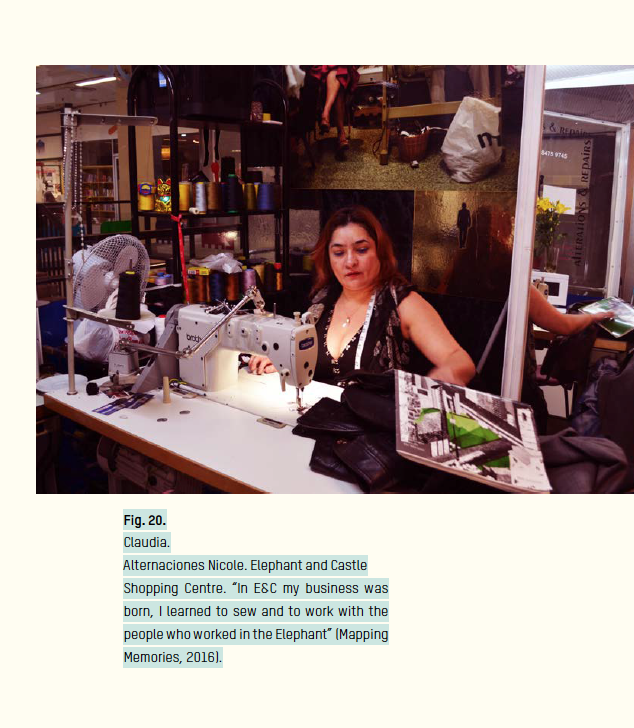

Claudia, [Fig.20] one of the retailers, that has been working in the E&C shopping Centre since she arrived in London, 22 years ago, pointed out that “You come to Elephant and it is as being in Colombia” (Mapping Memories, 2016). The area is enhancing social constellations of immigrants allowing them to feel comfortable and peaceful in the global city. In addition, this commercial space “facilitates transnational practices that keep them [Latin Americans] in contact with their families (…) the Shopping Centre advertises itself, as a second home for people who are far from their families” (Cock,2011, p184).

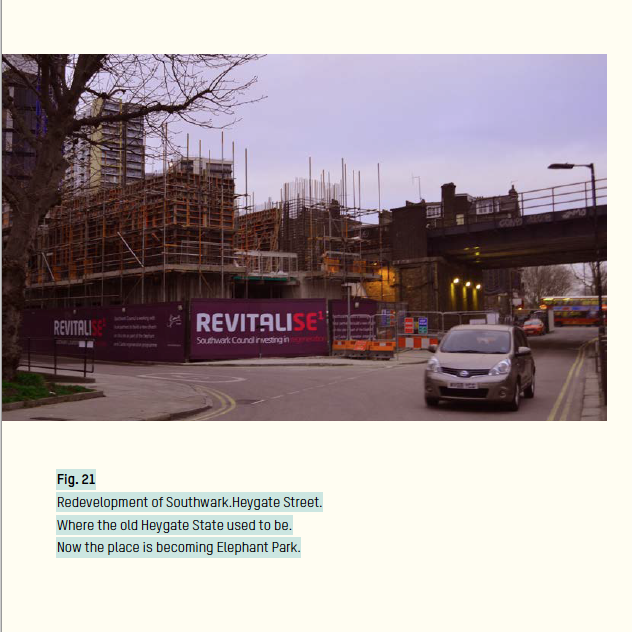

Sadly all of these practices are at risk due to the Southwark borough regeneration plan14, [Fig.21]. In that order many questions arise to the surface about how this process is affecting the community there? Is this place at risk of becoming an example of homogenization due to the redevelopment process? Who is going to be there? Who is able to afford new development prices? The idea of the place of community is in the atmosphere, is it going to survive the displacement? Is it important or not for London as a cosmopolitan and multicultural city to keep immigrants expressions and spaces? Is Elephant and Castle losing its traces as an immigrant spot? Can those traces be enhanced and give to the place a sense of cultural and visual identity?

Due to the reach of this work, all these questions are not going to be answered, but at least are going to denounce the situation in theoretical and academic terms in order to visualize the urban change and call for social awareness in regards to the Latin American community in London.

Simplicity Vs. Complexity

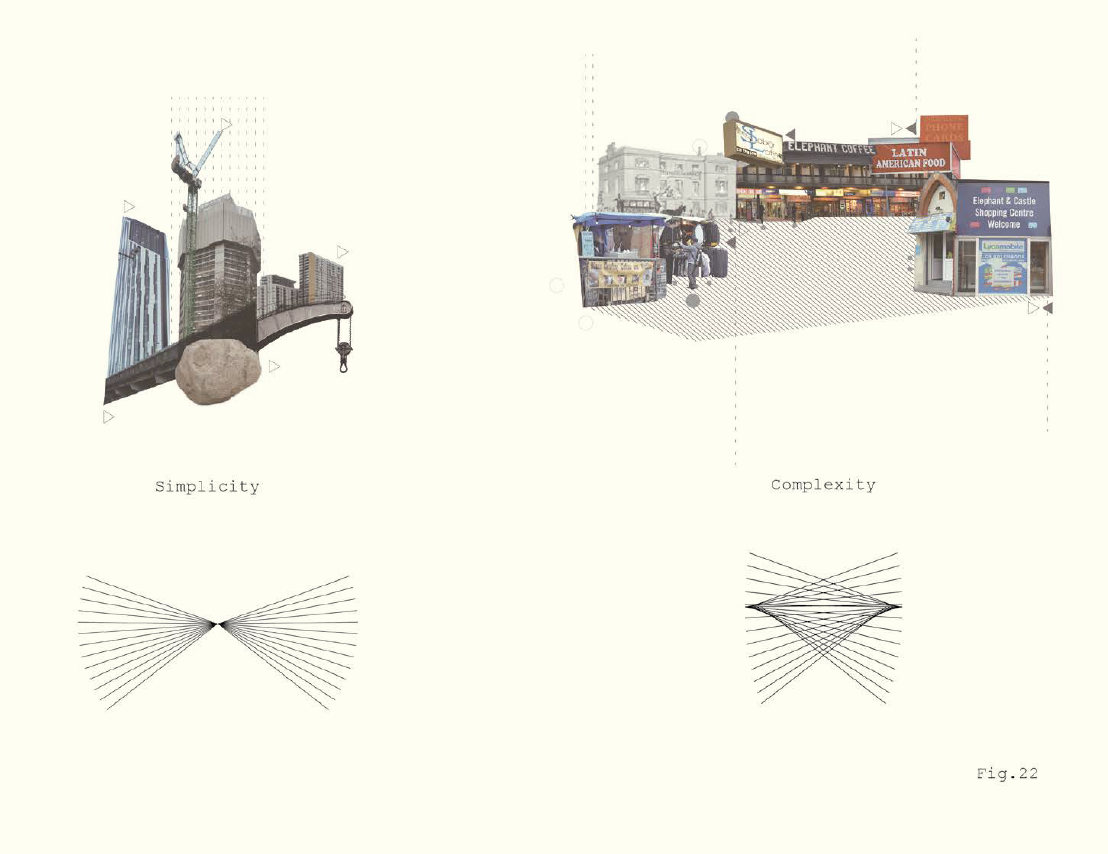

As Richard Sennett argues in the book The Craftsman: “Urban planning, like other technical practices, often zeroes in on needless complexity, trying to strip away tangles in a street or in public space. Functional simplicity carries a price; urbanites tend to react neutrally to stripped-down spaces, not caring much about where they are. “ (2009,p225) [Fig.22].

In relation to Elephant and Castle, Delancey and Lendlease, the developers15, projected the construction in terms of profit and no social approaches were made before starting the project. Although a couple of meetings with the community have happened, it was after calls from social leaders. Their necessities are not taken into account yet. Developers are just announcing that new thing that is going to happen. There is uncertainty in the atmosphere and the retailers are not sure about was is actually going to happen and what are their possibilities, this is due as well as the mind-set of the condition of an immigrant. As The report of the case of London Latin’s Quarter stands out “policy frameworks, local business environments and profiles of people and place to be fully inclusive of MEBs (Minority Ethnic Business). Only then will regeneration schemes fully utilise the role they can play in the transformation of local places and economies and help London to achieve its aspirations and vision of becoming a leading global city” (Román and Hill, 2016). Only if developers and government take into account migrant spots as opportunity places to enhance the transculturality aspect of the city, the whole problematic of belonging or not belonging will be considered in order to give a place in the city to the Latin American community.

In that sense, one can argue that it is possible to change places in fruitful manners constructing policies with communities and turning those ideas into realistic proposals. For example, many Latin American cities had have to deal with very problematic social issues such as: drug dealers, violence, forced displacements. Albeit, almost all of Latin America countries experiment enormously problematic social and cultural boundaries some cases have been studied by the academic Justin McGuirk in the book Radical Cities, in which the author refers to successful projects in Latin America that engage the community with the space, as a consequence the permeability between people from outside with the particular social group of the area is strengthened, resulting in new transcultural practices (Bond and Rapson, 2014) that nourish the social dynamics of each city. As a particular case the author refers to Medellin’s Social Urbanism as “the power that a community possesses to effect radical change when it engages in the political process” (McGuirk, 2014, p235). This acknowledgment is linked to Sennett’s complexity in two ways. Firstly, the social aspect of urbanism, that refers to Medellin treated as a laboratory conducting ‘social workshops’ in order to develop the Urban Land Usage Plan16. Secondly, if Sennett’s definition of urban design as a complexity processes are transported into social and cultural procedures within new development of E&C, one can argue that complexity is a proper way to describe the importance of taking into account needs instead of developing under simplicity parameters17, such as demolition and construction of something completely new that just leads to profit and a way to sell the project to the new Londoners18. The importance here is to keep the Latin American atmosphere, in that order London will be keeping its Palimpsest character, its layers of cultural diversity.

Community places vs. private and public spaces

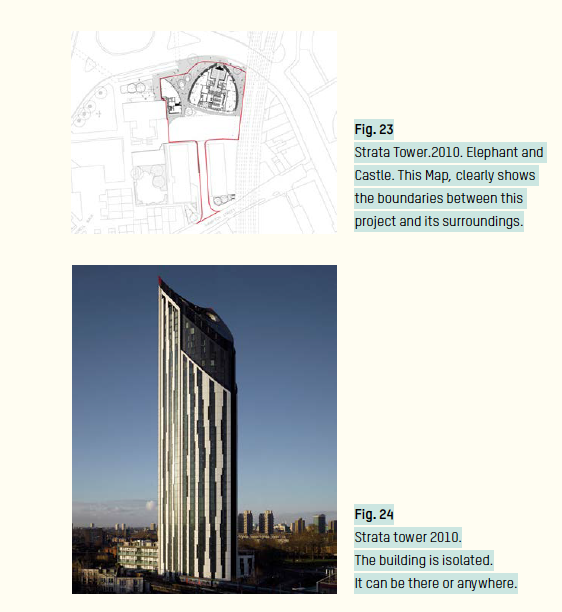

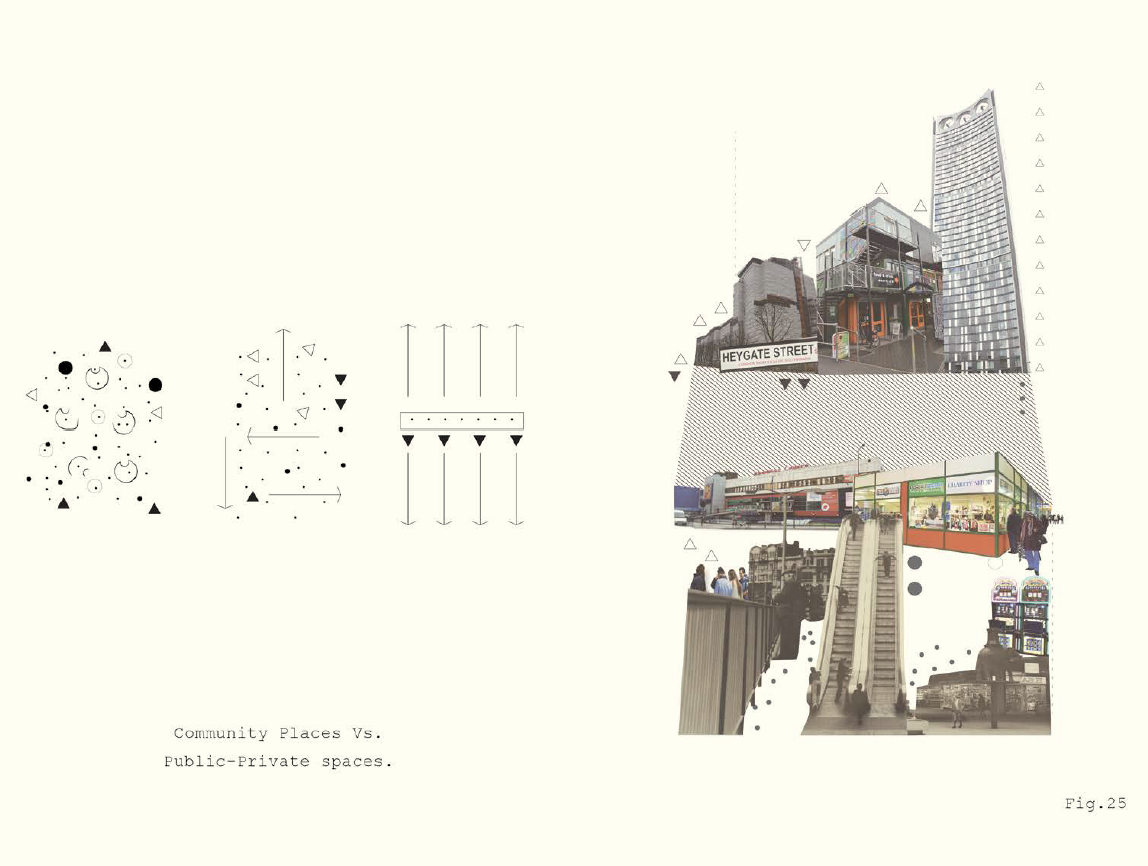

It is not a secret that London nowadays is facing a massive restructuring pattern, that is pushing minor ethnic communities apart. As a result places that used to be visited and frequented by particular communities are becoming touristic spots, shifting into what Augé has called non-places (2008). As an example the Strata Tower and Square [Fig.23 and 24] is a space of anonymity, where the identity of the surroundings is not recognised, on the other hand the case of the Shopping Centre presents ambivalence, between the place and the non-place character of that space. The sense of place there is enhanced by the Latin American community and retailers, who live and work around, yet the visitor can experience both types of space, depending on its mind-set and on who is influencing him. In this case the developers here are addressing the definition of non-place as a space that has no identity, a place of sameness that does not allow the contruction of community (Ibid), is a space where everything looks like a pattern of contemporary urbanism, where the corporate city is erasing the traces of the urban neighborhood (Zukin, 2010). Evidently is the social diversity not the architecture and big developments the aspects that gives a soul to London. Elephant and Castle area does need more cohesion and can be more permeable with London. However, denying its identity will not solve the problem, the idea of shifting it into a public-private space is not coherent with the discourse of London as a welcoming city. Is it just welcoming for people with economic power?

The biggest problem of converting E&C into a non-place is the loss of cohesion. Redevelopment and revitalisation process in London are taking for granted the factor of working with communities of the area, like gathering information from their traditions and diversity. Ann Minton argues that “turning places into consumer products tends to suck the original life out of them in all its diversity and unpredictability- with the consequence that places seem to become unreal, characterized by soullessness and sterility rather than organic activity” (2006, p26) [Fig 25]. If attachment to the place and the sense belonging are lost, the level of trust between people will disappear, blocking the permeability of the place (Sennett, 2009,p227).

Elephant and Castle is a community hub, where immigrants help each other, for example with visa documents GPS, National Insurance, and daily life situations as ‘unofficial’ citizens, if this place disappears this is not only going to affect Southwark, it will affect the whole Latin American community that lives and works in London19 (Mcllwaine, 2010, p7). The constant shift of a community place due to its privatization causes a fragmentation of society that in one way or another breaks the layers of historical London and vanishes the existence of communities in specific places.

As a conclusion: London’s Latin Quarter

Overall, this analysis looked at the character of London as a Palimpsest city that is risking its layers in order to become a homogenized spot, with great desire for economic profit. Furthermore, to illustrate that point the ideas of complexity considered in the light of Richard Sennett, questions the necessity of intervening places with the community as a process that involves delving into the space and understanding its dynamics from inside the social realm, the layers of the city could be enhanced rather than fragmented if the developers of new projects reinforce cultural-space networks. In addition the references to Ann Minton create inquiries around the privatization of the Shopping Centre area in Elephant and Castle, and the impact that action might have within the community. Also, this work provides evidence of the sensation of the inhabitants and retailers, like: fear, uncertainty and hope which are woven in the atmosphere and there is not a concrete answer in order to tackle these emotions and sensations. Still there are some possibilities, which I will come back to in the next paragraphs. Finally, it considered Justin McGuirk’s analysis on Latin American cities (2014) as a positive and accurate way to manage social disruptions within the urban fabric, such as the lost sense of belonging transforming places into sameness spots (Minton, 2006).

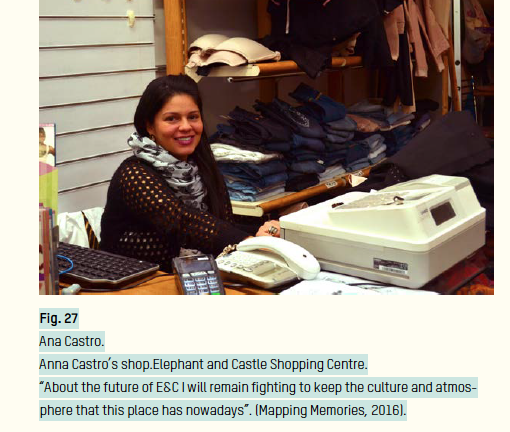

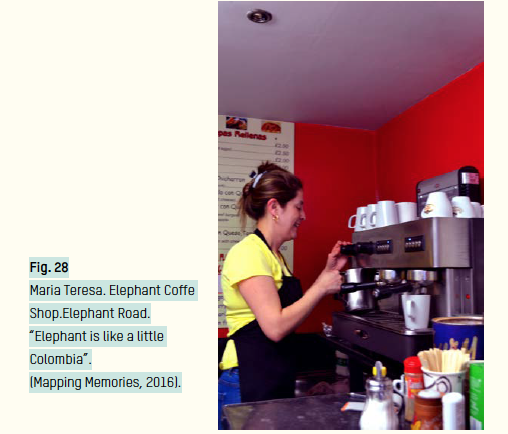

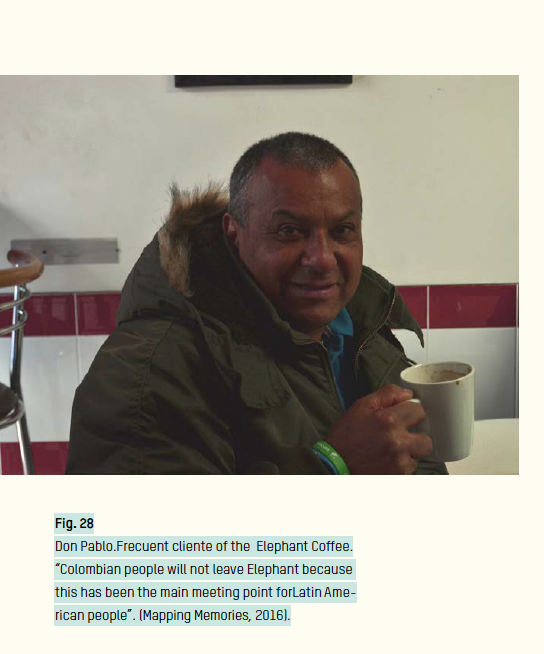

As recommendation one might suggest that for successful intervention on the part of Southwark council it would need to consider the Latin American sentiments and desires. In doing so, the work of Latin Elephant20, is an effective strategy for maintaining cohesion in the area, to tackle the negative effects of the urban change. There is fear and uncertainty in the atmosphere as Claudia, points out “I am sad because I feel that I have to leave the Shopping Centre, I don’t know if I will be re-located and that is stressful. I feel that I will lose the meeting points with Latin Americans”. (“Mapping Memories E&C,” 2016). [Fig.27,28 and 29].

Going back to McGuirk studies on Latin American sites, when the author quoted Sergio Fajardo’s statement22 “where there is fear there will be a fragmented society” (2014, p241), this approach can be interpreted in the E&C as fear from the unknown about what will happen, and the lack of communication on the part of the Council, it can be clearly seen a position where the one who leads the battle is the one with economic power, and the people who give the place its sense, its atmosphere, recover it from a derelict postwar area are in an uncertain terrain where nobody knows exactly what is going to happen. Indeed renovations on the space and public realm are great for the area, which is in need for a more integrative public space. Yet, the London plan must recognize the people who were there before and act in a conscientious way, that is to say, recognize the community in the first stage of the intervention proposal and acknowledge its needs, talking to them, inviting them to participate, creating spaces for dialogue and recognizing that they are the people that know the area as a whole.

Evidently, the uncertainty is the biggest problem within urban change, as the scholar and politician, Antanas Mockus claimed, “Without a sense of collective ownership, everything that should be public is inevitably annexed by private, commercial or authoritarian interests” (Cited in McGuirk, 2014, p213). In order that the proposal for an ‘official’ London’s Latin Quarter initiative of Dr. Patria Román [Director of Latin Elephant] which is seeking to agree on guarantees for the Latin American community and retailers with the Southwark Council to improve, expand, enable and cultivate social cohesion with new employment opportunities that will contribute to reinforce the levels of truth within Latin Americans, as well as create a more permeable membrane that allows social dynamics to follow from the Latin Quarter to the rest of the city (Román, 2016).

Finally, one might say that there is hope as well as doubt and fear. At the end nobody knows what will happen next, certainly the Southwark Council has the tools to tackle this problem in the manner they consider more accurate within their interests and most certainly Latin Elephant and the Latin American population will be claiming their place in the city, so it will be a long process. After all, “viewing the city intermittently is a process of unbearable and inexplicable anticipation, since any movement of the city in any direction is potentially possible” (Barber, 1995, p47).

Footnotes:

1 City experiment the closure of GLC [Greater London Council] which leads to the independent Borough Administration enhancing cold and warm spots, this political decision lead to the social division in terms of racial [ethnic] facts.

2 The Illustration Millenials-Creative Class was part of an analysis of Greenwich Peninsula. Created with Renata Guerra for the Module Interpreting Space at the University of Westminster.

3 Other areas facing similar process are: Stratford, Shoreditch, Whitechapel, Bentham Green, Greenwich and Seven Sisters.

4 As a matter of fact, looking at its architecture sets an example: from medieval architecture to Victorian houses, and then to new already made buildings using containers as the basis of contemporary architecture.

5 Regarding to the process that Berlin past through in order to overcome the Second World War damages.

6 See [www.elephantandcastle-lendlease.com] and [www.delancey.com/elephant-&-castle-redevelopment.html]

7 Where the Elephant with the howdah was first located before being installed at the Shopping Centre.

8 Which was rebuilt in 1818, later in 1898.

9 The pub was damage during the Second World War, so that the building was demolished and the public house was moved to another place close to the roundabout.

10 Inherited from the Soviet Union and the Nazi Diaspora to the continent. Dictatorships and Communist Governments.

11Evidently the wealthy ones in the North and the Working Class in the outskirts and South of London.

12 Elephant Road, Newington Butts, Eagle Yard Arches, and Old Kent Road.

13The author was refering to referring to Seven Sisters and E&C areas as meeting points particularly for Colombian people.

14 It started with the Heygate State, a housing state, close to the E&C shopping Centre, constructed in 1974 and demolished between 2010 and 2014 . Many people were evicted from the area, and now a new complex of buildings is under construction (2016 ).

15 See [ http://www.elephantpark.co.uk/local-area/elephant-and-castle] In the Elephant Park proposal, it can be seen how the space is going to be redevelop in total without taking into account the history of the place. It will be something completely new.

16 Urban Land Use Plan [Plan de Ordenamiento territorial] was the result of a collective effort made by politicians, entrepreneurs, students and local communities. Some of the projects that changed Medellín are: Parques Bilioteca [Library Parks], UVA [Unit of articulated urban life] and The Metro Cable [Cable Car as public transport] in order to satisfy population needs and desires to be included. Medellín is a city that faced massive immigration from the rural areas of Colombia in the 1990’s. Leading to unofficial settlements in the outskirts [Mountains]. The displaced people were an enormously isolated social group. Nevertheless with the social urbanism development the situation has been improving ever since. Nowadays the city is more inclusive with the majority of the inhabitants. Yet, there is still a lot of work to be done. For more information about Medellin’s process See [www.reddebibliotecas.org.co/grupos/sbpm], [http://lasuvadelavida.com] and [http://gondolaproject.com/medellin]

17 Such as: big public and green spaces, without any allusion to the local area, or global material that transform the space into a homogenized spot.

18See, for example, Strata Tower Project.

19 Which by 2008 were 113,500 and has continued to grow leading to strengthened retail and economic flows between Latin American and the UK.

20 A charity that is helping the community to overcome the redevelopment process, highlighting the Latin aspect of the locality in order to promote the Latin Quarter hub.

21 See [www.google.com/maps/d/viewer?mid=1aT5DrgYSVr0fGtl6xNzfByyTjpA]

22 Fajardo was the major of Medellín from 2003-2007 and is currently the governor of Antioquia department.

References:

Asante, M.K., 2001. Transcultural Realities and Different Ways of Knowing, in: Transcultural Realities: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Cross-Cultural Relations. SAGE Publications, Inc., 2455 Teller Road, Thousand Oaks California 91320 United States, pp. 71–82.

Augé,M., Non-Places, 2nd English language ed. (London; New York: Ver- so, 2008).

Barber, S., 1995. Fragments of the European city, Topographics. Reaktion Books, London.

Bond, L., editor of compilation, Rapson,J., editor of compilation, 2014. The transcultural turn : interrogating memory between and beyond borders, First Edition. ed, Media and cultural memory/ Medien und kulturelle Erinnerung ; v. 15. De Gruyter, Boston.

Campkin, B., 2013. Remaking London. IB Tauris & Co Ltd.

Cock, J,C., 2010. Migrant Capital a perspective on contemporary migration in London. City parochial Foundation. the Migrants’ rights network (Mrn), London.

Engbersen, G., 2001 .Focaal – European Journal of Anthropology no. 38, 2001: pp. 125-138

Guzmán-Ruiz, E., 2009. Artistic research scholarship: Urban palimpsest in Berlin after the fall of Berlin’s wall. DAAD, Berlín, Alemania

Hayden, D., 1995. The power of place: urban landscapes as public history. MIT, Cambridge, Mass; London.

Humphrey, S.C., author, 2013. Elephant and Castle: a history. Amberley Publishing, Stroud, Glos.

Huyssen, A., 2003. Present pasts: urban palimpsests and the politics of memory, Cultural memory in the present. Stanford University Press, Stanford, Calif.

Mesa, C., 2010. Superficies de contacto. Mesa Editores.

Medellín

McGuirk, J., 2014. Radical cities: across Latin America in search of a new architecture. Verso, London.

McIlwaine, C., 2010.No longer Invisible.The Latin American community in London. Queen Mary University of London.

McIlwaine, C. (Ed.), 2011. Cross-Border Migration among Latin Americans. Palgrave Macmillan.

Minton, A., 2006. The privatisation of public space: what kind of world are we building? Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors.

Ortiz, F., 1940. El Contrapunteo Cubano del Tábaco y el Azúcar. Pensamiento Cubano,

editorial de ciencias sociales. La Habana, 1983.

Porter,R., 2000. London: a social history, [2nd ed.]. ed. Penguin, London.

Roman-Velazquez, P & N. Hill (May 2016). The case for London’s Latin Quarter: Retention, Growth, Sustainability. A report for Latin Elephant & Southwark Council.

Sennett, R., 2009. The craftsman. Penguin, London.

Welsch, W., 1999. Transculturality: The Puzzling form of Cultures Today, in: Spaces of Culture: City, Nation, World. SAGE Publications Ltd, 1 Oliver’s Yard, 55 City Road, London EC1Y 1SP United Kingdom, pp. 195–213.

Zukin, S., 2009. Naked City: The Death and Life of Autentic Urban Places. Oxford University Press. London.

Image References:

Fig. 1- Posada, V., (2016). London: Living Organism [Digital image]

Fig. 2- Posada, V., and Guerra, R., (2016). Millenials Creative Class [Digital image]

Fig. 3- Posada, V., (2016). London as an Urban Palimpsest [Digital image]

Fig. 4- Rowlandson, T., for the “Illustrated London News” (1879). Elephant and Castle 1786 [Photographic copy of a print]. Available from Southwark Local History Library and Archives. Original Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Fig. 5- White, B., (n.d). Elephant and Castle [Photographic copy of a print]. Available from Southwark Local History Library and Archives.

Fig. 6- No author identified (1949). A view of the meeting place of six traffic arteries of London… where the emblem of the Cockney world looks down on London liveliest domain. [Copy of a photograph]. Available from Southwark Local History Library and Archives.

Fig. 7- H.T., Rolaui (1905).Elephant and Castle. [Copy of a photograph]. Available from Southwark Local History Library and Archives.

Fig. 8- No author identified (1898).Elephant and Castle (From Walworth Road)[Copy of a photograph]. Available from Southwark Local History Library and Archives, Donated by: Hawes, M.H.

Fig. 9- No author identified (1907).Elephant and Castle Theatre. [Copy of a photograph]. Available from Southwark Local History Library and Archives, Donated by: Mr. East, J.

Fig. 10- No author identified (1993). Meet you at La Fogata. [Southwark Newspaper]. Available from Southwark Local History Library and Archives.

Fig. 11- Daily Express (1959). Elephant and Castle Hotel. [Copy of a photograph]. Available from Southwark Local History Library and Archives.

Fig. 12- Pollard,J., (1826). View of the Elephant and Castle Pub. [Copy of a print]. Available from Southwark Local History Library and Archives.

Fig. 13- No author identified, Transport for London C. (1885). Elephant and Castle. [Copy of a photograph]. Available from Southwark Local History Library and Archives.

Fig. 14- Farrer, J., (1898). Elephant and Castle Hotel as proposed to be rebuilt. [Copy of a print]. Available from Southwark Local History Library and Archives.

Fig. 15- Prettejhons, L.G., (1956). Elephant and Castle Hotel (from Newigton Causeway). [Copy of a photograph]. Available from Southwark Local History Library and Archives.

Fig. 16- No author identified (1970). Elephant and Castle Shopping Centre design proposal. [Photograph]. Available from Southwark Local History Library and Archives.

Fig. 17- Burrow, J. &Co., (1963). Elephant and Castle redevelopment scheme [Photograph]. Available from Southwark Local History Library and Archives.

Fig. 18- No author identified (1965). Elephant and Castle Shopping Centre [Drawing]. Available from Southwark Local History Library and Archives.

Fig. 19- Brooke, R., (1976). Elephant and Castle Shopping Centre [Photograph]. Available from Southwark Local History Library and Archives.

Fig. 20- Posada, V. and Raigoso, L. (2016). Claudia. [Digital Photograph: Mapping Memories Project]

Fig. 21- Posada, V. (2016). Revitalisation.[Digital Photograph]

Fig. 22- Posada, V., (2016). Simplicity vs. Complexit. [Digital image]

Fig. 23- Townshend Landscape Architects (2010). Strata Tower. [Digital image]

Fig. 24- Townshend Landscape Architects (2010). Strata Tower. [Digital Photograph]

Fig. 25- Posada, V., (2016). Community places vs. private-places spaces.[Digital image]

Fig. 26- Posada, V., (2016). London’s Latin Quarter.[Digital image]

Fig. 27- Posada, V. and Raigoso, L. (2016). Anna Castro. [Digital Photograph: Mapping Memories Project]

Fig. 28- Posada, V. and Raigoso, L. (2016). Maria Teresa. [Digital Photograph: Mapping Memories Project]

Fig. 29- Posada, V. and Raigoso, L. (2016). Don Pablo. [Digital Photograph: Mapping Memories Project]

This work was developed as a text and image exercise for the module Interpreting Space. Arts and Visual Culture MA. Professor Steven Smith

- Fading Layers in London. The case of the Latin American community. - September 2, 2016

- What London offers for Brazil lovers - September 1, 2016

- Family Journey. Colombia into British Culture. - April 15, 2016

Wow, really must have missed this in school. The effort you have put into this article does not go unrecognized. Thank you for your hard work!

Mental Health Blog