Between now and the summer we are going to be showcasing the best of our original research by students in the School of Humanities at the University of Westminster. If you are a Humanities student at Westminster and would like to publish your research on our blog, please do get in touch! In the first of our commentaries, Eleanor critically analyzes the representations of autistic individuals in Sia’s 2021 film release Music. Eleanor is a BA English Literature and Creative Writing student in her final year. She likes animation, gaming, and poetry, and is hoping to become a screenwriter

The cinematic release of Music in 2021, directed by Australian singer and songwriter Sia Folger, might have marked an important attempt to better represent autistic individuals on film and so contribute to the wider and ongoing inclusion of marginalized people across the arts. It was, however, subject to intense criticism throughout its production, primarily in relation to the casting of an actor not on the autistic spectrum to play the lead role, and this may even have contributed to its failure at the box office (grossing $645,949 against its $16 million budget).

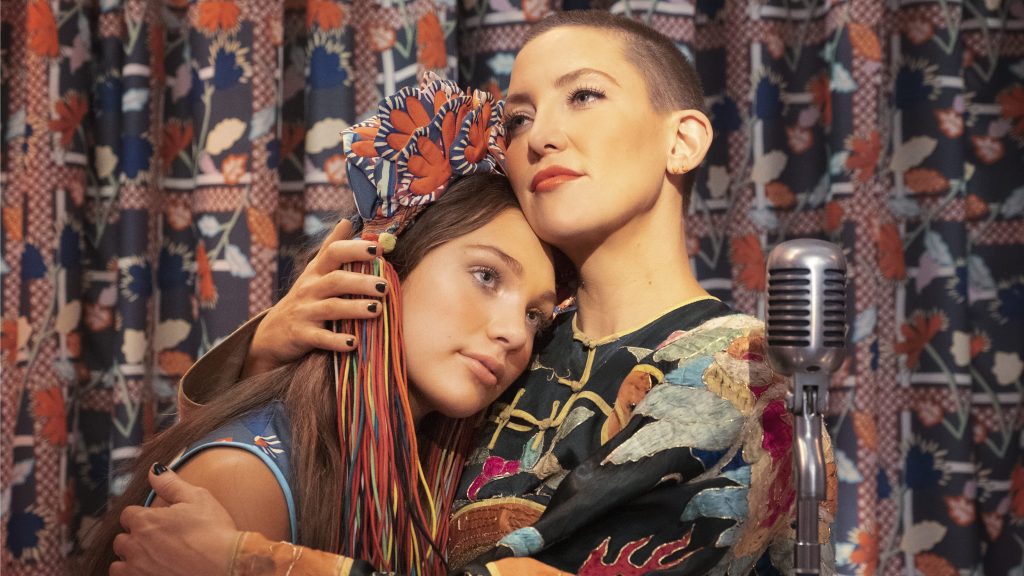

There has long been a debate over whether able-bodied or neurotypical people should play disabled or neurodivergent characters. Whilst non-disabled actors have been consistently awarded for such portrayals, only two disabled people have won acting Oscars. As a result, there have been increasing demands for disabled or neuro-divergent actors, who are significantly under-represented in Hollywood, to play these roles. It was therefore unsurprising when critics took to social media over the controversial casting of the dancer and actress Maddie Ziegler to play the lead role, a girl with autism named Music. What was perhaps more surprising was Sia’s justification of her decision, which was made, she said, because she had previously worked with a nonverbal autistic girl who found the experience of being on set “unpleasant and stressful” (Romano, 2020). Whilst the details of this situation are not known, some have argued that Sia did not make enough of an effort to accommodate this actress, and other autistic actors who reached out to Sia via social media were rejected. Ziegler had previously performed as a dancer in the music videos for Sia’s Chandelier and, alongside the actor Shia LaBeouf, Elastic Heart, and the director later claimed, “It’s actually nepotism because I can’t do a project without her” (Ntim, 2021).

Casting controversies aside, the film raises deeper questions around the representation of disability in ways that are inclusive of and resist the exploitation of the disabled people represented. The film uses strobe effects, which given roughly 12.1% of autistic people have epilepsy has the potential to cause seizures (Autistica, 2017), and multiple instances of bright colours and loud sounds, which have the potential to overstimulate any autistic person in the audience. Indeed, the film represents Music herself having a meltdown as a result of becoming overstimulated, in response to which one of her caregivers forcibly restrains her, saying that he is “crushing her with my love”. Yet this practice is traumatizing and can be dangerous, as the individual’s face and frontal part of their body are forced towards the ground, reducing their ability to breathe and in some instances resulting in death (Bastow, 2021). Although Sia later apologized and promised to either add a warning or remove this scene entirely, as of writing Amazon Prime still has the full film including this scene with no warning or acknowledgment of the issue.

Inaccessibility and poor research aside, many people felt that the film’s portrayal of autism itself was problematic, reducing Music to a stereotypical, infantilizing caricature. Music is effectively silenced in her own story. She is shown using an augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) device, a speech-generating tablet with buttons connected to different words and pictures. These are designed to help nonverbal individuals communicate for themselves but Music only ever uses it to say basic phrases such as, “I’m happy”, “I’m sad”, “I’m scared”, “yes” and “no”. AAC devices are usually programmed with thousands of different words, and having it shown in such a limited way undermines the intellectual capabilities of nonverbal autistic people.

This also contributes to the film’s creative inability to communicate Music’s perspectives or inner life, as a result of which she is a poorly written and one-dimensional character, who does not develop in any way over the course of the film. The audience learns almost nothing about her aside from her autistic traits, and her perspective on the events in her life is unclear. For example, at the beginning of the film Music witnesses the death of her grandmother; she is clearly agitated after finding the body and clearly aware that something is wrong yet depicted as perfectly content in the next scene, and the emotional grief that she would be feeling is never addressed. Whilst she is shown in some distress at certain points, these are only ever depicted through the perspective of the people around her. The film’s main plot primarily deals with the relationship between her caregivers and Music functions more like a plot device than a subject in her own right. This once again underestimates the intellectual capacity of autistic people whilst suggesting the misconception that autistic people do not feel emotions and lack the experience of empathy.

When the film does, occasional, make more creative attempts to represent the interior life of Music, these largely fall flat. There are innovative musical segments where creative set design is combined with interpretive dance sequences that have the potential to explore more psychological aspects of the plot. These remain, however, overly childish and simplistic, and contribute to the way Music’s character is largely stereotyped. One of her caregivers states that Music is “taking a snapshot” every time she looks at someone, which alludes to a belief that autistic people have a photographic memory, which although sometimes true is rare according to studies that have examined visual memory in autistic people (Semino, Zanobini, Usai, 2019). Together, however, these various characteristics play into the archetype of Savant syndrome, “a rare condition wherein a person of less than normal intelligence or severely limited emotional range has prodigious intellectual gifts in a specific area” (Nolen, 2009). Although a real syndrome, it is estimated to effect approximately 10% of autistic people and so, although a popular trope within the representation of autistic people, one that is in reality uncommon. As a consequence, the multiple and diverse ways that autism manifests itself in real individual becomes reduced a problematic and cliched archetype. The film is so poorly researched and inauthentic that it cannot accurately represent the nuanced experience of autism. Whilst disabled people deserve to see their lives and stories represented accurately in the stories they consume, the stereotypes created and reinforced by popular culture and the media have an effect on the way already-marginalised people are treated in real life. Disabled people report being denied adult treatment and a say in their own care, while autistic people who do not fit the stereotype of their condition may be denied a diagnosis by medical professionals and so support in educational settings.

This poses the question of who the film is really for. Sia states that the film was a “love letter to caregivers and to the autism community” (BBC, 2021) and, since the story and character development largely centres around Music’s caregivers, it could be argued that Music was intended primarily for the loved ones of autistic people. Nonetheless, parents and carers of autistic people have spoken out against the harm it caused, with Jennifer Litton Tidd, the mother of two autistic children, writing that certain parts of the film were “viscerally painful for me to hear” (Tidd, 2021). I would therefore argue that Music is primarily intended to provoke an emotional response from an audience that is otherwise unfamiliar with its subject matter, a phenomenon known in the sphere of disability activism as “inspiration porn”: the tendency for able -bodied or -minded people to portray those with disabilities as “inspiring” for the sake of invoking an emotional reaction (Boren, 2022). In this sense, Music is oriented towards the ‘neurotypical gaze’.

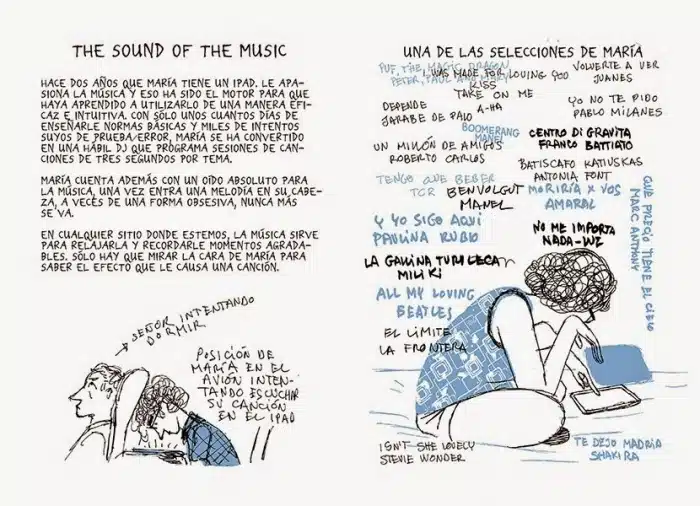

This neurotypical gaze may be avoided by involving autistic people in the film-making process. Sia admitted to conducting most of her research with the charity Autism Speaks, an organisation that has been widely condemned by the autistic community for spreading misinformation and villainizing autistic people, but there are plenty of resources created by neurodivergent individuals and multiple people reached out to Sia via social media to offer criticism in good faith. Benjamin Fraser (2018) has also shown how autism can be positively represented in art and culture, discussing how the Spanish graphic novel María cumple 20 años (Maria Turns 20) was produced as a collaboration between the co-authors Miguel Gallardo and his autistic daughter María, and featuring her drawings. The graphic novel successfully depicts autism as a shared experience between two people, focusing on their connection, similarities, and daily life. Importantly, “the text does not take a clinical or medical approach to autism, but it still attempts to deliver a message about autism to readers who may be less likely to acknowledge similarities between themselves and María” (Fraser, 2018, pp. 122). This practice of collaboration and inclusion avoids reducing the character’s personality to aspects of her autism, representing her aversion to unfamiliar situations as something she shares with her father and her habit of pinching people as a form of communication, and in doing so captures her own uniqueness and individuality more effectively. Writing can be an effective way to broaden our minds and understand other people and is always a collaborative experience, whether consciously or otherwise, so engaging with accounts from the people you are trying to represent is absolutely necessary in order to portray their experiences accurately; not only are marginalised people under-represented in the arts, but they are the experts on their own experience.

Bibliography

Autistica (2017). ‘Epilepsy – Autism’. Available at: https://www.autistica.org.uk/what-is-autism/signs-and-symptoms/epilepsy-and-autism (Accessed: 25 November 2023).

Bastow, C. (2021) ‘Sia’s film Music misrepresents autistic people. It could also do us damage’, the Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2021/jan/27/sias-film-music-misrepresents-autistic-people-it-could-also-do-us-damage(Accessed: 24 November 2023)

BBC (2023) ‘Sia reveals autism diagnosis, two years after film backlash’. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-65764285 (Accessed: 24 November 2023).

Boren, R. (September 7 2022) Stimpunks Foundation. Available at: https://stimpunks.org/glossary/inspiration-exploitation/ (Accessed: January 11 2024).

Fraser, B. (2018) Cognitive Disability Aesthetics : Visual Culture, Disability Representations, and the (In)Visibility of Cognitive Difference. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3138/9781487515119.

Furler, S. (dir.) (2021).Music. Vertical Entertainment, 2021.

Nolen, J.L. (2009) ‘savant syndrome | Definition & Facts’, Encyclopedia Britannica. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/science/savant-syndrome (Accessed: 28 November 2023).

Ntim, Z. (2021) Sia says casting Maddie Ziegler over an autistic actor in her new film was ‘nepotism’. Available at: https://www.businessinsider.com/sia-defends-casting-maddie-ziegler-over-autistic-actor-nepotism-2021-1?r=US&IR=T#:~:text=The%2045%2Dyear%2Dold%20singer,I%20don’t%20want%20to. (Accessed: January 9 2024).

Romano, N. (2020) ‘Sia responds to backlash after casting Maddie Ziegler as autistic teen in film ‘Music’’, Entertainment Weekly. Available at: https://ew.com/movies/sia-music-movie-autism-controversy/ (Accessed: 25 November 2023).

Semino, S., Zanobini, M. and Usai, M.C. (2019) ‘Visual memory profile in children with high functioning autism’, Applied Neuropsychology: Child, pp. 1–11. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/21622965.2019.1594231 (Accessed: 24 November 2023).

Tidd, J.L. (2021) Alliance Against Seclusion and Restraint. Available at: https://endseclusion.org/2021/02/16/i-watched-music/ (Accessed: January 10 2024).

- A Marseille Journal (Part 5) - 17 May 2024

- A Marseille Journal (Part 4) - 17 May 2024

- A Marseille Journal (Part 3) - 16 May 2024