Report By Harry Eagles (MA English Language and Linguistics)

On Thursday 27th February, 2020 – in what can now feel like a strangely simpler time, before the lockdown in which we all find ourselves began – I and five other MA students on Dr Sylvia Shaw’s ‘Language and Gender’ module took a trip to the Houses of Parliament. The aim of the visit was to see the Hansard report in action – and to examine from a linguistic perspective how this ostensibly ‘verbatim’ report of parliamentary discourse is created, and what kinds of ‘representation practices’ (Slembrouck 1992: 101) are at work in this process.

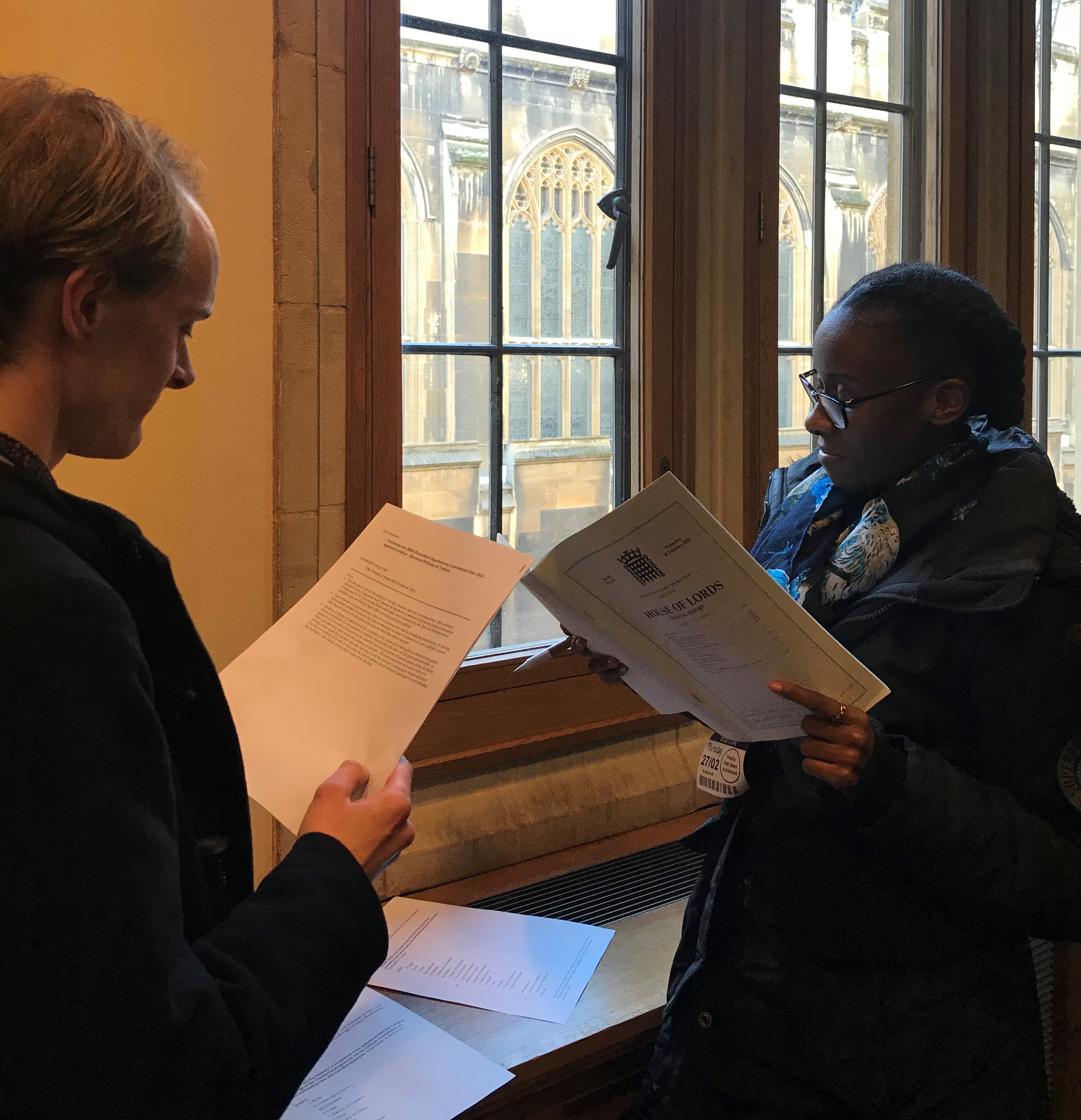

Our trip began with a visit to the House of Commons, where we were faced with several stages of strict security (and airport-style bag and coat checks) on entering. Eventually, we made it up to the public gallery in the Commons, where we spent twenty minutes watching a rather sparsely attended sitting of ‘Business of the House’, during which MPs from all parties posed questions on a number of issues to the Leader of the House (Conservative MP Jacob Rees-Mogg). After this, and a quick lunch in the public Jubilee Café, we moved on to a meeting room where we were met by John Vice, the Editor of Debates at House of Lords Hansard, and Gráinne McGinley, one of its Managing Editors, who between them gave us an introduction to Hansard and prepared us for the main event of the day – shadowing a Hansard reporter at work.

‘Substantially Verbatim’: What Hansard Does

Hansard’s official website describes it as ‘a “substantially verbatim” report of what is said in Parliament’. Published every day in print and online, and dating in its official form back to 1909 (and to the early 19th century as an unofficial report), it offers a record of everything that is said in both parliamentary chambers. Hansard reporters – whose ranks have included Charles Dickens, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and William Hazlitt (Vice and Farrell 2017: 15) – spend fifteen minutes at a time in the chamber, listening to what is being said and taking notes. Historically, this note-taking process – often done in shorthand – was presumably much more arduous than it is nowadays, as all proceedings are now recorded so that the reporter can listen back to them later. After their shift, a reporter has a short window of time to get the text of what was said down on paper and edit it into publishable form, after which it is sent on to a subeditor for finetuning, and the reporter returns to the chamber for their next shift. All in all, we were told, there is a gap of only three hours between something being said in the chamber and it appearing on Hansard Online.

Each of us shadowed a reporter for one shift in the chamber itself – during which we had the opportunity to ogle the extraordinarily ornate gold throne at one end, with awe or distaste depending on the ogler’s political leanings – before going up to the Hansard office to watch the ‘substantially verbatim’ report being created. And this is where things get interesting linguistically. Hansard Online further defines ‘substantially verbatim’ as follows: ‘Members’ words are recorded, and then edited to remove repetitions and obvious mistakes, albeit without taking away from the meaning of what is said’. In reality, the editing process is rather more transformative.

In a 1992 article, the linguist Stef Slembrouck looked at the Hansard report from a discourse-analysis perspective, and demonstrated some of the ways in which the actually spoken ‘anterior discourse’ is transformed into a represented ‘reported discourse’. Features of this ‘reported discourse’ include the fact that it is essentially ‘translated’ from spoken language to formal, written language: colloquialisms, regionally marked forms, and other features of spoken language such as false starts and repetition are removed, and the text is edited to add ‘explicitness’ and ‘well-formedness’ if these qualities are deemed missing. Hansard also privileges ideational utterances, i.e. those that are concerned with the transfer of factual information; more interpersonal meanings, such as hedges and expressions of a speaker’s stance towards what is being said, are frequently deleted. Making a section of speech conform to the above conditions can involve fairly significant changes – well beyond the ‘substantially verbatim’ – as Slembrouck demonstrates with numerous examples. Indeed, one thing said by the editors we spoke to on the day – that the impression Hansard wants to create is ‘not that one person said it, but that one person wrote it’ – seems to demonstrate a recognition of this more transformative role.

Nor do MPs and peers seem unaware of the extent of the changes to what they have said. Emma Crewe, an anthropologist who has written on the House of Lords, quotes a peer who describes Hansard’s work as making parliamentary discourse ‘homogenous. It works against the spirit of independence. The ragged edges get smoothed over…’ (Crewe 2010: 319).

The reporter I worked with exemplified some of the levels at which spoken language is transformed in the process of editing, although it must be said that none of his interventions were as drastic as some of those detailed by Slembrouck. To give just one example, in a discussion of ‘early-years interventions to support children and families’, one speaker had said the following:

As someone who did not relish school holidays, she has in me someone who is going to take this matter seriously.

This was rewritten on the grounds of improving its ‘well-formedness’ (since it was the speaker who did not relish school holidays, not her interlocutor) as follows:

She has, in me, someone who did not relish school holidays and who is therefore going to take seriously these matters.

Here, the intervention is fairly innocuous: it would be hard to argue that the ideational meaning is changed, but the tone has clearly been elevated, by the reordering above as well as the addition of the connective ‘therefore’ and the formulation ‘to take seriously these matters’, both of which are characteristic of written rather than spoken language. It is clear from the extent of these changes that in general, such interventions carry the possibility of at least altering the interpersonal meanings of utterances (as one might argue the increase in formality in the above example does), and that a very careful hand would be required to guard against this tendency. Indeed, Slembrouck provides a number of examples in which Hansard’s editorial preferences come together to significantly change both interpersonal and ideational meanings. At another point, the reporter I was shadowing mentioned removing ‘unnecessary’ words as being part of his remit; but clearly, determining what is ‘necessary’ is a difficult and subjective task, and one which cannot be sure of leaving ‘meaning’ intact.

Admittedly – and as indicated by these rather modest examples – my brief experience of Hansard suggested that things may have changed somewhat since Slembrouck’s 1992 study. A subeditor I shadowed implied that practices have become more liberal regarding the elimination of colloquialisms and informal language; while there was a time when nearly all contractions would have been removed in the editing process, for instance, this is no longer the case. However, my experience suggested that there is still a sizeable gulf between Hansard’s stated aim of a ‘substantially verbatim’ report and its actual editorial practices. It should also be noted that another aspect of the Hansard report’s aim is to create a record of parliamentary discourse which is easy to read; as any linguist knows, a more accurate transcript can be anything but. However, we might still reasonably wonder whether the kinds of interventions discussed above are necessary to create a readable account.

It would also be interesting, especially for scholars of language and gender, to examine gendered aspects of representation in the report: unfortunately, our short visit did not allow for insights of this kind, but a sustained study might be able to investigate whether there are any differences in how speech is represented relative to the gender of the speaker. Given the prevalence of what Deborah Cameron and Sylvia Shaw (2020: 145, among other works) call the ‘different voice ideology’, or the belief that women ‘do politics’ (and more widely, communication) differently to men, it would be worthwhile to examine whether any ‘different voice’, real or imagined, is present in the Hansard report.

Works Cited:

Cameron, Deborah, and Sylvia Shaw. 2020. ‘Constructing Women’s “Different Voice”: Gendered Mediation in the 2015 UK General Election’. Journal of Language and Politics, 19:1, 144–59.

Crewe, Emma. 2010. ‘An Anthropology of the House of Lords: Socialisation, Relationships and Rituals’. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 16:3, 313–24.

Slembrouck, Stef. 1992. ‘The Parliamentary Hansard “Verbatim” Report: The Written Construction of Spoken Discourse’. Language and Literature, 1(2), 101–20.

Vice, John, and Stephen Farrell. 2017. The History of Hansard. London: House of Lords Hansard and House of Lords Library.

- English Language and Linguistics Research Seminars 2020/2021 – University of Westminster - October 6, 2020

- ‘Not That One Person Said It, but That One Person Wrote It’: Language and the House of Lords Hansard - May 1, 2020

- Conference: French Creoles, Contact Languages: Homage to the Late Professor Philip Baker - February 3, 2020