Author: Dr Brad Elliott, Senior Lecturer in Physiology, School of Life Sciences, University of Westminster

According to the United Nations, the world’s population crossed the 8 billion people line on the 15th November, 2022; a lot has been written about this event, and will continue to be, with regards to sustainable populations, constant growth, and economic implications.

But while people have become used to the world’s population continuously growing, what happens when it doesn’t? In some countries the populations growth (simply put, births minus deaths) are shrinking. In the United Kingdom, this is currently being offset by inwards migration, but in countries such as Japan, we’re seeing ‘negative growth’, or the country’s population decreasing overall. This has resulted in a rapidly ageing population; the average age of society is shifting upwards. Over the next decades, this trend is expected to occur globally, and we’ll become an ‘ageing world’.

My research focuses on the biology of ageing, trying to explain the how and why musculoskeletal function changes with age. Many people assume that the frailty of ageing is inescapable, as you grow older, your bones will get weaker and your muscles will decay away. Much of the work we’re currently doing is showing that to only be partly true, and that it’s quite possible to maintain ‘young-like’ muscle function into your 60’s and 70’s.

The UK is Growing Older

In the UK, 1 in 5 people are currently over the age of 65, and by 2050 this is predicted to be 1 in 4. This has significant implications for the nation’s healthcare, taxable income if you’re a government providing services such as the NHS, and how your society operates overall. As we recently identified in Understanding ‘Early Exiters’; The Case for a Healthy Ageing Workforce Strategy, the UK’s ageing population is unique. Unlike peer states in Western Europe, since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic the UK has experienced a significant rise in 50–64-year-olds who have involuntarily left the workforce. Currently in the UK 1 in 7 people between the ages of 50-64 are not in the workforce.

“No other high-income country has seen a comparable sustained rise in over 50s remaining economically inactive since the start of the pandemic. The phenomenon of ‘Early Exiters’ is a very British one.”

– From Understanding Early Exiters

The reasons why the UK specifically had significant numbers of middle-aged-to-older people exiting the workforce is undeniably complicated. A major conclusion of the research conducted for this report was that chronic long term health conditions resulted in people being unable to work, but unexpectedly that Long Covid specifically was rarely one of them. ‘The Pandemic’ caused people to exit the workplace, but not Covid per se. However, it’s important to note that age and disease do not have to go hand in hand. Indeed, poor health and chronic health conditions are better predictors of absence from the workforce, not age.

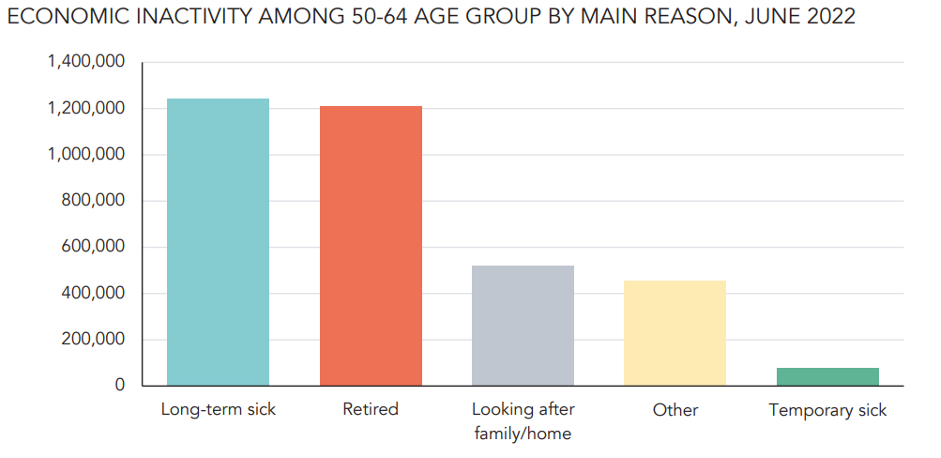

ONS data suggests that the two major reasons why over 50’s leave the workforce are either long-term sickness or voluntary retirement (graph above). Our focus group data revealed that many people would state ‘retired’ as their main reason for leaving work, however their underlying choice to retire was long-term health reasons, either their own or of a close family member who required care. It appears that ‘retired’ as a category for leaving work was also capturing a significant number of long-term sickness cases. In June of 2022, 2.2 million people aged 50-64 were outside the workforce either due to being retired or having a long-term health condition.

“Most ‘Early Exiters’ we spoke to felt like they had no choice but to leave work early, despite the financial risks of doing so”

– From Understanding Early Exiters

What Solutions Are There?

Having identified many people in the UK were involuntarily outside the workforce, and that this number was only expected to grow in the short-to-medium term, we wanted to provide a range of policy based cross-party recommendations that could address this issue. These recommendations spanned short, medium, and long term changes and can be briefly synthesized as:

- Support older people with health conditions to continue working

- Help older people with health conditions to return to work

- Medium-term prevention by improving the quality and design of work and the workplace so that they support older workers’ health

- Long-term prevention by improving public health over the course of people’s lives, and by advancing scientific research, including physiological research, on ageing.

The ‘Levelling Up’ strategy by the current government included a statement that the UK should aspire to increase healthy life expectancy by 5 years, but this is currently not being met. As our society continues to age, both the effect of long-term health conditions must be addressed in the short-term, and in the longer-term adequate research needs to be undertaken to understand how and why we age, and what can be prevented with age to help maintain a healthy older population who can both work and live as independently as possible. As the wider worlds society ‘catches up’ and experiences ageing populations, what lessons the UK learns over the next few decades on supporting an ageing population will need to be transferred globally.

More information about the Ageing Workforce report launch and highlights by The Physiological Society can be found here.

Featured image credit: Center for Ageing Better Image Library

Author: Dr Bradley Elliott is a Senior Lecturer in Physiology at the University of Westminster, where his research examples the physiology of human ageing. He also has a science communication role, writing for several publications and regularly appearing on documentaries on ageing, as well as participating in policy discussions on human ageing. Besides his academic role, he is also a Trustee of the British Society of Research on Ageing.

- Obesity as a genotoxic environment - April 28, 2023

- Dalit History Month and its significance - April 20, 2023

- A professor is going to live in an underwater hotel for 100 days – here’s what it might do to his body - April 13, 2023