Author: Dr Beth Parkin

When we think about climate change, we may not immediately realise the impact our diets are having on the planet. The meat and dairy industries are surprisingly large polluters that account for approximately 25% of global greenhouse gas emissions, and the impact of these industries alone will prevent us from reaching internationally agreed climate change targets. Animal-based foods in particular require large amounts of land and energy. In fact, twice as much greenhouse gases are emitted in their production compared with plant-based food.

Reducing meat intake at a population level is one area where small changes in everyone’s behaviour can accumulate to have sizeable impact. For example, if every person in the UK were to switch just one beef or lamb-based meal a week to a plant-based option, the nation would benefit from an 8% reduction in domestic greenhouse gas emissions. With this in mind, our current study examined how we can best promote plant-based food in those who routinely eat meat.

As we routinely make decisions around food, many of these choices become habits. This habitual thinking relies on our fast, intuitive mode of decision-making that is largely unconscious. Importantly, this type of thought is triggered automatically by cues from the environment. Because of this we explored how changing these cues or the context in which the decisions are made in might be effective in promoting plant-based food.

We examined the impact that availability of plant-based food on a menu has on choice behaviour, by comparing menus that had different proportions of meat to vegetarian food. While it may seem intuitive that increasing the availability of plant-based food will make us eat more of it, little is known about whether this actually works in practice. In addition, while there has been a recent large growth in the plant-based food sector, with higher quality, more visible meat alternatives now on offer, our consumption behaviours show that we are currently eating more poultry than ever before.

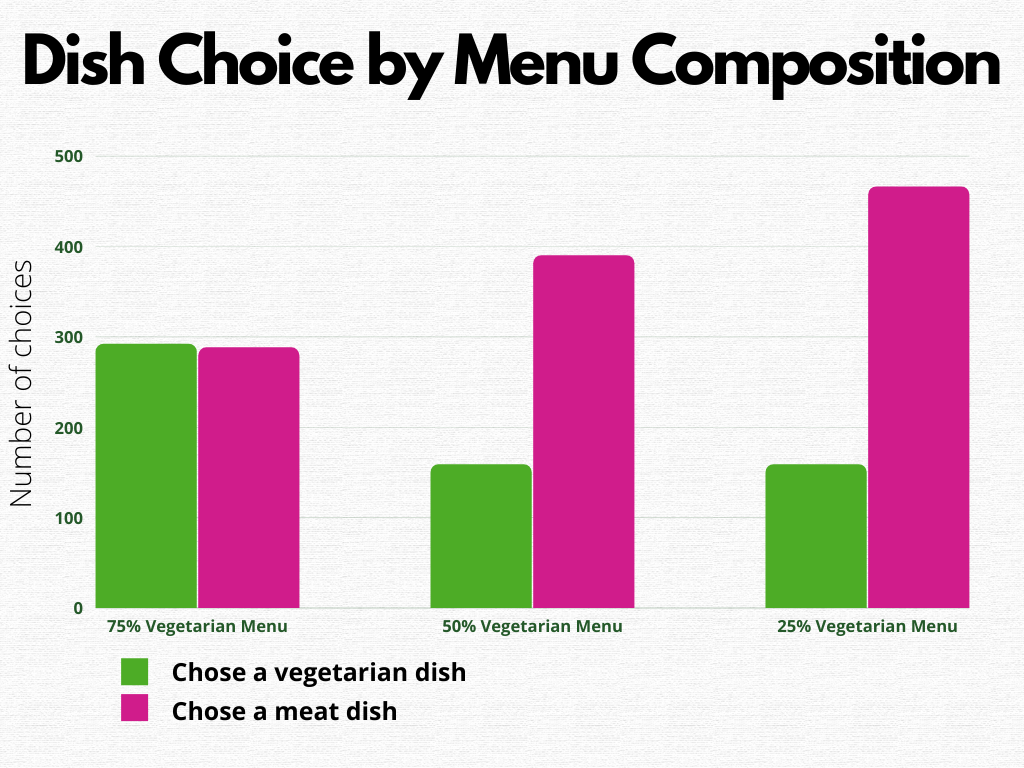

By comparing the choices of meat eaters when presented with menus which were composed of either 25%, 50% or 75% vegetarian dishes we could determine exactly how far meat availability needs to decrease to affect meat eaters’ food choices. In this study participants made hypothetical food choices about what dishes they would most likely order from the menu.

Our results showed that making vegetarian food more available does significantly encourage sustainable food choices. However, routine meat eaters only shifted their choices to vegetarian food when these items made up 75% of the menu, but not when menus were half meat and half vegetarian, or when menus were 75% meat. In fact, the likelihood of a participant choosing a vegetarian meal was almost three times greater when the menu was 75% vegetarian compared to when the menu was 50% vegetarian.

While the reason for this effect is unknown, we think that increasing the availability of vegetarian food may unconsciously suggest socially acceptable norms. Alternatively, they could be providing customers with a wider range of options that they might not have previously considered.

The study is important in highlighting the power that the food service sector has in creating large scale shifts in reducing the global emissions around food. It provides practical advice on what percentage of food offerings should be vegetarian if we are to succeed in encouraging sustainable eating behaviours at scale. The UK food service currently offer menus with a ratio of 30% vegetarian and 70% meat. Our findings show that this ratio needs to be flipped, with plant-based food items making up the majority of the menu to promote significant shifts in vegetarian food consumption.

Author’s biography:

Dr Beth Parkin is Senior Lecturer in Psychology at the University of Westminster, School of Social Sciences. She holds a PhD from the Applied Cognitive Neuroscience Laboratory at UCL and studies the psychology and neuroscience of goal directed behaviour.