Author: Dr Brad Elliott

Cycling into work in a chilly -1ºC morning in London got me thinking about this year’s Winter Olympics in Beijing. You see, this Olympics has been cold. This may sound like a silly statement, but stick with me. Yes, it’s winter, there’s snow on the ground, etc. But at the Alpine Zhangjiakou venue for skiing and snowboarding events, it’s been colder than a lot of athletes are used too. Windy, cold, dry races on the Zhangjiakou Zones have been causing skiers some problems.

Human beings are remarkably successful species in a number of ways, and our ability to regulate temperature in the wide variety of global environments is one example of this. Physiologically, we regulate our internal body temperature very carefully despite what’s going on outside, keeping our cells pretty close to their optimal 37ºC. Heat production is primarily a by-product of mitochondrial metabolism: little tiny sub-cellular factories burn oxygen and nutrients to produce energy for our cells to function. Heat loss from our bodies occurs via a number of different mechanisms. Radiation is the most obvious. When our body is warmer than outside (a pretty typical situation), we radiate heat into the environment like a heater. Conduction is another obvious one, and works throughdirect contact. If we touch something that’s warmer, we gain heat from it, and if we touch something colder, we lose heat. Convection is similar, the flow of air over our body makes us gain heat if the air is warmer, and lose heat if the air is colder. I like to think of these two as cooking: conduction is like cooking in a pan, convection like cooking in an oven. Finally, evaporation, or loss of heat when fluids evaporate off our skin. Does this sound familiar? This is why we sweat, small amounts of water on our skin evaporate, making this a much more effective way of losing heat than other methods.

Evaporation is why getting wet, either in cold water or in rain near zero degrees, can become dangerous quickly. As long as we stay relatively dry and it’s not too windy, exercising in cold isn’t physiologically that hazardous. In fact, as we approach zero degrees, some types of endurance exercise can become more physiologically efficient. Marathon runners make their record attempts early in the morning, partly because that’s when the air is cool, and a typical guideline for endurance sports is to start your day feeling like you’re one layer under-dressed for the current temperature, because you’ll soon warm up. Between zero and -20ºC with no wind or rain, one or two layers of clothing will keep the air close to your skin warm and minimise convective heat loss, keeping most people comfortable for extended periods of time exercising. Layers are important; depending on exercise intensity, you may even overheat during exercise in cold environments and want to de-layer, but when you stop moving/skiing/running, you’ll cool down rapidly and want to layer back up and move into a warm environment if you can.

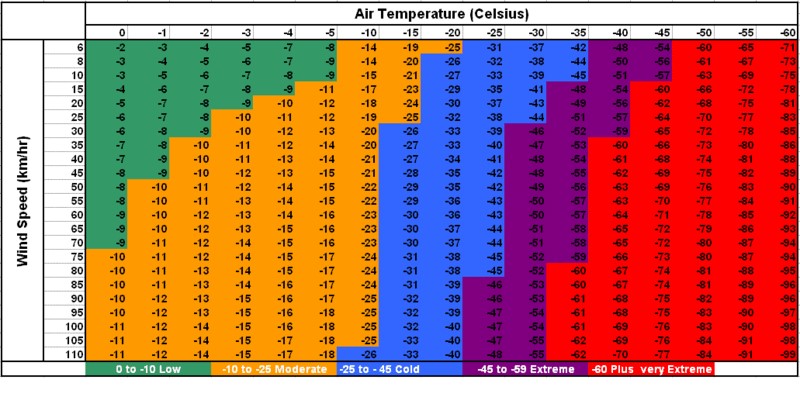

When it’s windy, however, you get increased convective heat loss. This is known as wind chill, which is why cold weather climates often report two temperatures (e.g., “-12ºC today plus a mild breeze, so it feels like -18ºC”). When considering events in cold weather, we need to consider both the ‘absolute’ temperature and the windchill-induced ‘feels like’ temperature. This is what the athletes in the alpine venue of Zhangjiakou are struggling with, temperatures that don’t seem too cold at first – “only” -10 to -20ºC or so – but with the addition of wind speed and the speed that racing athletes are moving, serious risks of frost bite on exposed skin occur within minutes.

So, it’s cold. What can we do about this? Biathletes in particular have been struggling. Outdoors for extended periods, moving quickly and exposed to the wind. Remember, if there’s a 20km/h wind that you’re skiing at 20km/h into, you’re experiencing 40 km/h of wind speed on your face and suddenly -20ºC feels more like -35ºC. Some strikingly non-streamlined scarfs, fluffy neck gaiters and gloves have been cropping up in practices and even races. Rumours have it heated socks and gloves are also being used to help warm vulnerable extremities. Athletes have even been seen with tape on their cheeks and noses to try and stop windchill causing frostbite on this remaining exposed skin.

Frostbite is a particularly awful experience, trust me. As the water in the cells of your body freezes, it forms crystals that rupture and kill the cells. If it’s “just” superficial skin layers, it’s painful but not so serious, but deep tissue frostbite leads to lost fingers, toes and ears through a delightfully named process known as ‘auto-amputation’. The tissue dies, turns black and falls off. I’ll refrain from linking any pictures here.

The message here isn’t avoid exercising when it’s cold. Far from it. Be smart, know how cold, wet and windy it’s going to be and plan to manage it. Have a warm ‘out’ option in case temperatures change quickly. Going back to my case this morning, as I reached campus on my bike, I was plenty warm enough, very pleased it wasn’t raining, and as it was only -1ºC no face tape for me today.

Author’s biography

Dr Bradley Elliott is Senior Lecturer in Physiology at the University of Westminster, where his research focuses on the translation of basic science into human clinical practice. He specialises in understanding and minimising the effects of ageing.