Entry by Lauren Nader

Definition:

Howard University School of Law explains the term ‘womanism’ in the sense that as ‘Black women have a higher likelihood of experiencing violence, receiving lower pay, and seeing fewer media and political representations of women who look like them. Because the mainstream feminist movement does not begin to cover this one-two punch of racism and sexism, a paralleling womanist movement formed to acknowledge black women’s specific struggle for equality’ (Capatosto, 2021).

You might be wondering what the difference between womanism, and feminism is? In essence, the terms ‘womanism’ and ‘feminism’ are closely related in the sense of fighting for equal rights of women however, ‘womanism’ focuses on specifically black women and women of colour. The distinction between the two key words should be clearly emphasised because it should be made clear that white women benefit from an advantage when referring to the terms ‘feminism’ or a ‘feminist.’ Womanism allows an area of focus for underrepresented women of society, those originating from ethnic minorities. They experience the struggles of sexist comments and challenges such as a lack of senior positions and the gender pay-gap nevertheless, they experience this through much more of an unfair lens. Furthermore, they face prejudices in the image of racism and segregation. They are made to feel different not only because of their gender but because of their skin colour and ethnic background. Therefore, although all females should be treated equal to their male counterparts, it is important to acknowledge the nuanced experiences of Black and women of colour (BIPOC), which includes black and indigenous women such as Aboriginal Australian women and Native American women. As well as women of colour (POC) in terms of different skin tones.

Historical context:

Author and activist Alice Walker first coined the term ‘womanism’ within her 1982 novel, In Search of Our Mothers’ Garden: Womanist Prose, in which she defines a womanist as,

‘A Black Feminist or feminist of colour, a woman who loves other women sexually or non-sexually and sometimes individual men sexually or non-sexually. She is committed to the survival and wholeness of all people. Male and Female. She isn’t a separatist except periodically for her own health. She loves: music, dance, the moon, the Spirit, and loves love and food and roundness. She loves struggle, people and loves herself’ (Blaque, 2019).

Walker further states that a ‘womanist is to feminist as purple is to lavender’ in The Colour Purple (1982) and it is through this powerful statement, she attempts to show the distinction between ‘feminism’ and ‘womanism.’ Womanism derives from the term feminism and is essentially a type of feminism. Similar to lavender being a shade or a ‘type’ of purple, this comparison seeks to show that they are related however unrelated at the same time. Perhaps it could be looked at in the sense that on the surface, the colour purple seems to be one shade, however when it is really analysed it can be seen in many different shades. For example, a blackcurrant’s purple is quite darker than a violet’s purple but extremely darker than a lavender’s purple. These three objects are naturally different shades of purple yet they may be categorised as one colour: purple. In relation to the skin tones of individuals, white (usually middle-class) women can be classified as ‘purple’ however, black women and other women of colour can be classified as ‘lavender.’ They are all women however different through their skin colour. Walker wanted to establish a clear distinction among feminists in the hope to show the increasing oppression that black women and women of colour face in comparison to white women.

An important moment in British feminist history was in 1903 when Emmeline Pankhurst, her daughters Christabel, Sylvia and Adela Pankhurst, and a small group of women founded the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) in Manchester. The Suffragettes were part of the ‘Votes for Women’ campaign that had long fought for the right of women to vote in the UK. They used art, debate, propaganda, and attack on property including window smashing and arson to fight for female suffrage. Suffrage means the right to vote in parliamentary and general elections’ (The Museum of London, n.d.). When individuals think of the Suffragette movement, they may typically refer to the white middle-class women who sought to earn equal status to men, however this was not always the case. The movement also consisted of other races such as Black and Asian women from upper-class societies as well as women from lower classes such as working-classes from all types of ethnic backgrounds (Crawford, 2018). They believed that they should also have the right to vote and make decisions that would impact the future of the country. Acts as such should not be made purely by men of society at the time e.g. their husbands but instead should allow for both sexes to provide an input. It took a large amount of bravery for these women to fight for what they believed in and they positively impacted a lot of women during this time and up until now. Moreover, their actions resulted in great achievements by women eventually earning the right to vote in UK elections.

Nonetheless, this achievement also suggests that the achievement of white middle-class society at the time may have been more superior to those from other ethnicities and social classes. These women may not have had to work because their husbands worked and thus they would be more concerned with looking after their children (when their nanny did not). They most probably had maids to take care of the cooking and cleaning. Fundamentally, they did not face the challenges that a lot of women at time would have faced that were from lower classes of society or from different parts of the world. These women faced sexism but solely sexism; whereas other women faced much more than sexism. Other women did not have the luxury to leave their children in care for the day and create signs and banners and walk around protesting for their rights to vote. Firstly, they did not have the time for this. Secondly, even if they tried, they would not be acknowledged. No one would listen to them or even give them a second of their time to regard the importance of their proposal. This is because they did not have white privilege. No matter how underrepresented they were, they were not white and therefore seen as less important within society at the time.

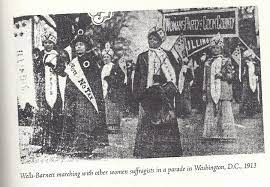

When exploring the historical context of ‘womanism’, it is important to explore the role of women of colour in the early feminist movement. It should be recognised that it was not until the 1965 Voting Rights Act that all African Americans were given the right to vote (California Commission On The Status of Women and Girls, n.d.). Initially, the ‘fight began in the 1800s alongside the women’s suffrage movement’, however it was a difficult proposal (California Commission On The Status of Women and Girls, n.d.). Ida B. Wells founded the Alpha Suffrage Club and was one of the founders of the National Association of Black Women. Their motto was lifting as we climb (Seattle Channel, 2020). This symbolises their accomplishments as they continue to be challenged yet elevate at the same time. When Michelle Merriweather, Commissioner of the Washington State Women’s Commission, was interviewed by Seattle Channel, she enlightened on the point that the founders of Delta Sigmatatis Sorority Incorporated, 22 female college students, their first act of public service when they became an organisation was marching in a women’s suffrage march. She went on to mention that even though they had to march in the back, they were women, they were present and as a result of this, they led the way for thousands of women (Seattle Channel, 2020). This demonstrates how much this meant for Black women because although they continued to be segregated within society, they did not let this discourage them from standing up or their beliefs. It is important to understand that Wells did not agree with the decision for Black women to stand at the back and thus, she ran to the front once the parade began. She was outspoken regarding her beliefs as a Black female activist, which led to much public disapproval (National Park Service, n.d.). The fact that Wells ignored the rules highlights her strength as an activist, she was not afraid of the consequences as she believed that her rights were more important.

Figure 1: An image of Ida B. Wells protesting during the 1913 National Suffrage Parade in Washington D.C., USA (Truth-Telling: Frances Willard and Ida B. Wells, n.d.).

Womanism in relation to pedagogy and higher education within the UK:

Representation of females that are underrepresented within society is now becoming more evident throughout higher education within the UK. More universities are creating BAME student networks where students from Black, Asian and other ethnic minorities can ‘come together, discuss the issues affecting them, and campaign to improve their student experience’ (University of Westminster Students’ Union, n.d.). As well as this, student unions offer cultural societies such as the African and Caribbean Society and the Bangladesh Society. It should be argued that places of contact and support such as networks and societies are really important because it allows students to feel understood. It creates a much more inclusive atmosphere in a university setting by encouraging diversity and cultural acceptance among students.

Moreover, contemporary degrees like “Women Studies” and gender-related modules taught within the social and political sciences provide an education that seeks to offer a comprehensive understanding of the experiences of those that identify as female and/or queer, and often encourages their empowerment. During the 1970s, the ‘women studies’ degree was established and led to a massive turning point for women as they could be further represented within the university system. It should be acknowledged that ‘multiple women’s studies programmes were launched and feminist content and pedagogies developed (David, 2016), despite frequent sidelining (Weiner, 2006). Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, ontological tensions and boundary debates emerged in the shift from women’s studies to gender studies’ (Coate, 2018; Henderson, 2018; Morris et al, 2021, p3). It could be said that with this degree came mostly women who wanted to study as men may have felt that they did not know how they could contribute to studying a degree as such. As a result, as part of a renewal of the degree, it became renamed ‘Gender Studies’ in order for students to perceive the degree as a study of equality within the sexes rather than purely looking at sexism. It could be argued that ‘traces’ of the feminist history of Women’s Studies that lurk in today’s Gender Studies classrooms can be somewhat baffling for contemporary students’ (Coate, 2018, p485). It could prove difficult to move past the previous curriculum of the degree and focus on new and improved solutions to learning about gender empowerment. This change should be seen as positive because there has been a lot of work that has been achieved since the days of the suffragettes and thus the curriculum should acknowledge these. Lecturers should now base their lessons on the continuation of work that needs to be performed. A large part of this focuses on the foundation of womanism as students should learn about the differences between Black and other women of colour and White women. The distinction between the treatment of women based on their races should be key topics of discussion.

It is often quite rare to notice events related specifically towards black women. Womanism should be more acknowledged. The Black Lives Matter Movement, particularly during the Spring 2020 protests, became more acknowledged by the world after George Floyd’s death. In terms of the UK and higher education, students, staff members and universities supported the movement by creating social media posts, sharing posts, reading books by black authors, purchasing from black-owned businesses, signing petitions, donating and protesting. This shows the vast range of actions that individuals are capable of if they want to make a difference to the world. All those that were involved in standing up against the racism and violence of black people and continue to fight for this should be regarded. The fact that racism continues to exist today is extremely concerning. This is exactly why feminists should acknowledge womanists and regard the term as its own because this gives a sense of power to black women (and other ethnic minority groups). They should have their own term which is purely for these women in order for society to recognise them in the way they deserve.

It is important to note that ‘the UK is now second in the international rankings for women’s representation on boards at FTSE 100 level, with nearly 40% of positions held by women, compared with 12.5% 10 years ago’ (Timmins, 2022). This is a great achievement for women and is proof that the work of feminists and womanists is being considered. However, there are a couple of problems that continue to exist. Firstly, it does not clearly state the ethnicities of these women. Secondly, although this 40% figure is a massive improvement, females should at least equate for 50% of these roles in comparison to males. As well as this, a pay-gap continues to exist between men and women with male employees earning on average 10.4% more compared to their female colleagues (Timmins, 2021). Again, this does not provide a breakdown of the salary differences for different ethnicities. Although women suffer in the working world, black women suffer the most. In fact, ‘only 21% of C-suite leaders are women, only 4% are women of color, and only 1% are Black women’ (Lean In, n.d.). Thus, universities should stand with these students and ensure that they provide the most effective support that they can in order to prepare these students for their professional careers. They must be prepared for the discrimiantion that they could potentially face, and universities should work with employers to reduce the impact of this on students.

References:

Americans Who Tell The Truth (2013). Alice Walker | Americans Who Tell The Truth. [online] Available at: https://www.americanswhotellthetruth.org/portraits/alice-walker

California Commission On The Status of Women and Girls (n.d.). Women of Color and the Fight for Women’s Suffrage | CCSWG. [online] Available at: https://women.ca.gov/women-of-color-and-the-fight-for-womens-suffrage/

Capatosto, V. (2021). A Brief History of Civil Rights in the United States. [online] library.law.howard.edu. Available at: https://library.law.howard.edu/civilrightshistory/womanist

Coate, K. (2018). Teaching gender: an inter-generational discussion. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 26(3), 485

Crawford, E. (2018). The black and Asian women who fought for a vote. BBC News. [online] Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/in-pictures-42837451

Investopedia. (n.d.). Who’s in the C-Suite? [online] Available at: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/c-suite.asp#:~:text=%22C%2Dsuite%22%20refers%20to

Kat Blaque. (2019). What Is: Womanism. YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xWgOpOkSCOI

Lean In. (n.d.). What Black women are up against. [online] Available at: https://leanin.org/black-women-racism-discrimination-at-work

Morris, C., Hinton-Smith, T., Marvell, R. and Brayson, K. (2021). Gender back on the agenda in higher education: perspectives of academic staff in a contemporary UK case study. Journal of Gender Studies, 3.

Museum of London. (n.d.). Who were the Suffragettes? [online] Museum of London. Available at: https://www.museumoflondon.org.uk/museum-london/explore/who-were-suffragettes

National Park Service (n.d.). Teaching Justice: Ida B. Wells in the Suffrage Procession (U.S. National Park Service). [online] Available at: https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/teaching-justice-ida-wells-suffrage-procession.htm

Seattle Channel (2020). Untold Stories of Black Women in the Suffrage Movement. [online] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Br6b9sIuIDU&t=400s

Timmins, B. (2022). Almost 40% of UK FTSE 100 board roles now held by women. BBC News. [online] 22 Feb. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-60430198

Timmins, B. (2021). Pay gap between men and women fails to improve. BBC News. [online] 6 Oct. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-58786739

Truth-Telling: Frances Willard and Ida B. Wells. (n.d.). Truth-Telling: Frances Willard and Ida B. Wells: Postscript: Ida B. Wells [image]. Available at: https://scalar.usc.edu/works/willard-and-wells/postscript-ida-b-wells

University of Westminster Students’ Union. (n.d.). BAME Students’ Network @ University of Westminster Students’ Union. [online] Available at: https://www.uwsu.com/groups/bame-students-network

What is white privilege? (2021). BBC News. [online] 22 Jun. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/newsbeat-57567647

Suggested Readings:

Science Encyclopedia (n.d.). Womanism – Bibliography. [online] Available at: https://science.jrank.org/pages/8159/Womanism.html (a 5-minute read that explains the concept of womanism)

Trueman (2015). Feminism and Education. [online] History Learning Site. Available at: https://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/sociology/education-and-sociology/feminism-and-education (definitions for the multiple types of feminism)

Voices of Youth. (2016). Lavender and Purple: Feminism and Womanism. [online] Available at: https://www.voicesofyouth.org/blog/lavender-and-purple-feminism-and-womanism (a human rights (feminism related) post by two young writers as part of UNICEF’s digital youth community)

Questions to ask:

- Are you a feminist or a womanist?

- Have you ever experienced any form of racial discrimination?

- If you are a woman that is part of BIPOC/POC, do you feel supported in your community, whether this be at university, work or in your everyday life?

- What could you do today to help black women and other women of colour in the fight for equality?

- White Guilt - October 20, 2022

- Colourism - October 5, 2022

- Microaggression - September 28, 2022