Written by Caterina Bellinetti

On February 14th, the death of Liang Jun was reported by international media. Liang, a woman born from a peasant family in Heilongjiang in 1930, became a Chinese national hero thanks to her work as a tractor driver. During her life, Liang was glorified by state propaganda as a model worker and, in 1962, she became the face of the one yuan banknote where she is portrayed while driving her tractor. The glorification of working women was systematically employed by the CCP in its propaganda strategies in order to promote the Socialist cause and bring more women into the workforce. The story of Liang Jun, her popularity, and the use of her image prompts us to wonder what it means to look at the representation of women in Chinese propaganda posters on International Women’s Day.

Liang Jun on one yuan banknote. Image credit: Creative Commons

Women have been a central part of modern Chinese political discourse since the May 4th Movement between 1910 and 1920. Right from its birth in 1921 in Shanghai, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) welcomed the feminist ideology of the Movement and included in its political agenda the promotion of women’s rights. In 1922, the Party embraced the celebrations for International Women’s Day and with it the call for gender equality and the right for women to vote. A few years before, in 1919, a young Mao Zedong, also influenced by the May 4th Movement, had criticised the ways in which traditional Chinese society treated women. In his famous essay Miss Zhao’s Suicide, Mao argued that Miss Zhao, a young girl promised in marriage to an old widower, did not actually commit suicide but was murdered by society. The three circumstances in which Miss Zhao found herself caged were Chinese society, her family, and the family of the man she did not want to marry. “Within these triangular iron nets, however much Miss Zhao sought life, there was no way for her to go on living.” noted Mao, “The opposite of life is death, and so Miss Zhao was obliged to die.”

Despite the proclaimed good intentions and the attempts, some successful, to include and ameliorate women’s living conditions, the Party fell short. Women’s issues were frequently dismissed in favour of the Socialist Revolution or the freedom of the country—especially during the war against Japan—and this contributed to the prolonged, hard-to-overcome existence of patriarchy. Propaganda posters, just like other forms of visual representation such as woodcuts and photographs, were not an exception. Created by a Party and an ideology that were male-oriented, the posters presented a view on the world of women that did not correspond to and eventually failed to alter the status quo of Chinese society. Women’s representation in posters was constructed through a male-gaze: when women were represented as leaders, they were in charge of other women, not men; when they were learning how to read and write, they were usually taught by their sons. Even if the Party was advocating for women’s equality, the visual representation of women remained stuck in the old narrative that presented them through their primary roles as mothers, sisters, and wives.

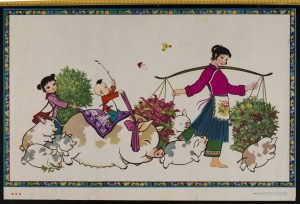

Hard working sister-in-law (1960). Image credit: University of Westminster’s China Visual Arts Project

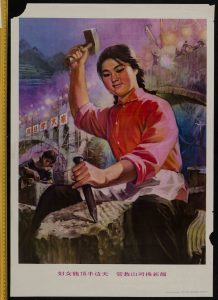

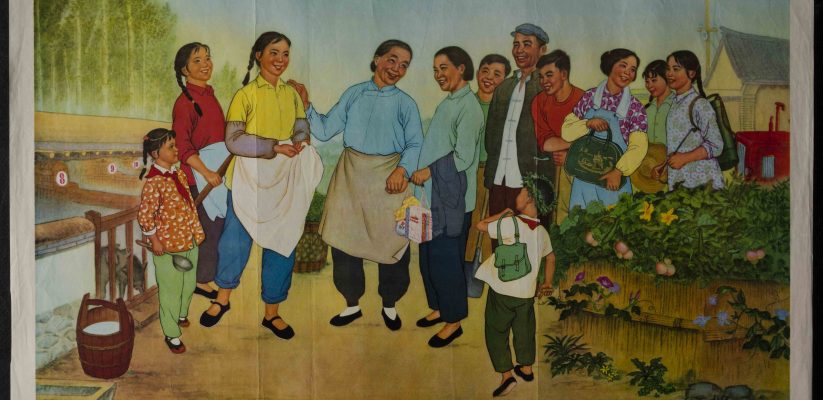

In the posters, women were predominantly young and beautiful, and their work efforts were directed to the family or the State. More interestingly though, they were always happy. When working in the fields or chiselling stone blocks with perfectly combed hair and red cheeks, a happy and determined smile appeared on their faces. Similarly, when women were portrayed while taking care of the family and performing their duties as wives, mothers, and daughters, they looked happy and gracious. In Communist visual propaganda, happiness lost its private connotation and became a public, national affair. Women were happy because, and thanks to, their work for the country and the Party. Being happy, therefore, became a duty.

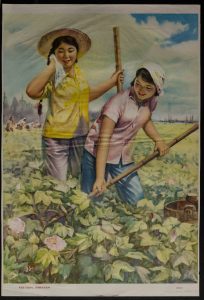

If you want blossoms full of folliage, study good management techniques (1964). Image credit: University of Westminster’s China Visual Arts Project

The duty of happiness reads like an oxymoron, but, according to Gerda Wielander, it was and still is a central part of the Chinese propaganda system. While, as Wielander argues, in the 1950s the focus of the Party was on “building a happy society,” in more recent years “social stability and regime maintenance have become the main goal.” The importance of happiness can be seen as part of the emotion work that characterised the CCP’s propaganda efforts since the Anti-Japanese War (1937-45). Defined by Arlie R. Hochschild as “the act of trying to change in degree or quality an emotion or feeling,” emotion work was frequently used by the Party to create a sense of unity in the people and the hope for a bright, happy future under the guidance of the CCP. In her essay Moving the Masses: Emotion Work in the Chinese Revolution, Elizabeth J. Perry noted that Mao Zedong believed that “mass ecstasy […] was efficacious not only for revolutionary struggle, but for dramatic economic breakthroughs as well.”

Women can hold up half the sky; surely the face of nature can be transformed (1975). Image credit: University of Westminster’s China Visual Arts Project.

Along the decades, women like Liang Jun were glorified by the Party for their work and family achievements and portrayed accordingly. Based on the awareness that a positive attitude and contagious enthusiasm were strong psychological weapons to mobilise the people in political and economic campaigns, the Party systematically exploited happiness throughout its visual propaganda. Women’s reality was not as joyous as modern Chinese propaganda depicted in the posters. Behind the smiles, the perfectly combed hair, and the rosy cheeks, Chinese women fought, struggled, and suffered as many of them have narrated in their memoirs. If in propaganda posters women’s happiness became a duty, in the real world it was too frequently an unreachable state or at last a very arduous journey.

Dr Maria Caterina Bellinetti is a writer and art historian. She received her PhD in History of Art from the University of Glasgow. Her thesis “Building a Nation: The Construction of Modern China Through CCP’s Propaganda Images” looked at how the Chinese Communist Party created and exploited photographic propaganda during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-45). She contributed with an essay to the forthcoming book—”Watering My Horse by a Spring at the Foot of the Long Wall”—by the Chinese-Dutch photographer Xiaoxiao Xu. You can follow Dr Bellinetti on Twitter @ducky_cat. Featured image credit: University of Westminster’s China Visual Arts Project.

Latest posts by kehoes (see all)

- TV Drama Discourse on Stay-at-home Fathers in China: Super Dad & Super Kids - January 28, 2022

- Freud and China - January 20, 2022

- “Cultural China 2020″—A Different Take on China - January 7, 2022

[…] un très intéressant post publié pour la journée internationale du droit des femmes, « Women Model Workers and The Duty of Happiness in Chinese Propaganda Posters », Caterina Bellineti revient également sur cette question : « La représentation des femmes dans […]