Written by Fan Yang

Throughout the medical response to Covid19 in the People’s Republic of China, over 50% of doctors and 90% of nurses were women. However, across the rhetoric of “soldiers fighting in the national crisis”, representations of medical workers across mainstream media sidelined and even erased femininity in order to serve the masculine cause. There was much publicity around female medical workers having their heads shaved before their departure to Wuhan, the city in China that experienced the highest number of Covid19 infections, and around a nurse coming back to work 10 days after experiencing a miscarriage and claiming the title of “macho-man” for self-encouragement. In this masculinized morale-boosting propaganda that circulated nationwide, the physiology of female medical workers was rendered expendable, thus invisible and unattended. It was not until the hashtag activism # Sisters Fight Against Coronavirus in Comfort that was launched by feminist blogger Liang Yu on Weibo, the most popular social media platform in China, that companies and philanthropic funding began to deliver sanitary goods to hospitals in Hubei province. This hashtag activism not only catered to the real needs of female medical workers, but also brought women’s menstruation to the fore of public discussion. I will argue that during the pandemic, menstruation became a site of power negotiations between the state, hospital managers and feminists. The hashtag activism helped to mainstream the discourse of menstruation and was intended to challenge the culture of period shaming. However, as we will see, the discussion of menstruation did not take place in an inclusive way, failing to take account of women who do not menstruate and people of other genders who do. In this way, the cisgender binary remained unchallenged across these public discussions.

Chinese state media ignored and sidelined the issue of menstruation among female medical workers. On February 17th, a nurse in Wuhan mentioned menstruation during her interview on CCTV13 but this reference was later cut out in the afternoon re-run. On the one hand, non-menstruating female medical workers fit the narrative of the masculine hero across publicity campaigns. ‘Girl talk’ such as menstruation should be confined to the private sphere rather than being made public, it appeared. On the other hand, if the menstruation of female medical workers was not visible, their material need for sanitary goods could thus be neglected. Sanitary goods for women were not included in the governmental supply of anti-pandemic necessities. These necessities prioritized personal protective equipment, which claimed to be gender neutral, yet were actually based on male standards. For instance, the supply of only large sized protective clothes failed to take into consideration small-sized women, which increased their risk of infection given that the poor fitting protective gear allowed in air.

Hospitals functioned as legal recipients for donations of sanitary goods. But the elimination of menstruation from mainstream media representations blinded hospital managers, usually male, to the needs of female medical workers. As pointed out by Liang Yu, hospital managers at first turned down offers of sanitary goods by saying that “these are not necessary” (Pan 2020). It was left to hospital managers to decide whether sanitary goods could be successfully distributed to female medical workers who were in urgent need of them but felt too awkward to bring it up. The power dynamics between male superiors and female inferiors as well as masculine ideals over ‘shameful’ female physiology were intensified across hospital spaces during the crisis. The interference by male hospital managers in the distribution of sanitary goods also included re-distribution of some sanitary goods intended for women to male medical workers. Period diapers were taken away by men for use during long working hours, despite the fact that they were not intended to be used in that way. Female medical workers had to ask Liang to request donations of sanitary pads instead of period diapers, as the latter would only end up going to male colleagues, causing a scarcity of sanitary resources for women. From rejecting to dividing up donations of sanitary goods, hospital managers inherited the logic from the state, that is, of ignoring women’s physiology. The masculinization strategy from the state to hospitals during the Covid19 crisis neglected the particular needs of female medical workers.

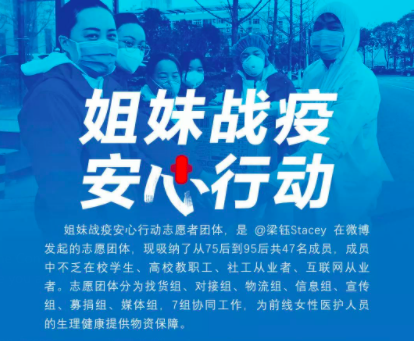

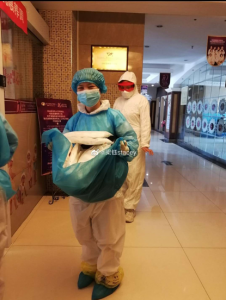

The hashtag activism # Sisters Fight Against Coronavirus in Comfort was launched by Liang Yu, a feminist blogger on Weibo, on February 6th. After the case of the Feminist Five in 2015, in which five feminist activists were arrested because of their public campaign against sexual harassment, feminist activism in China shifted from offline to online. Weibo became the major social media platform for hundreds of thousands of grassroot feminist bloggers, with different scales of followers discussing and debating women issues. As of March 22nd, the hashtag mobilization of donating sanitary goods succeeded in collecting 2,532,044.88 RMB, benefiting over 84,500 women (@梁钰stacey). The volunteers involved in fundraising the purchase and delivery of sanitary goods were mostly women. This female alliance was formed under the slogan “sisters save themselves”, which emphasized the marginalized status of female voices and the absence of governmental support for female medical workers during the pandemic. The highly efficient hashtag activism was credited by China Women’s Development Foundation, the official charity organization for poverty-alleviation and women’s development under All-China Women’s Federation (ACWF), in its post on Weibo. The dialogue between the grassroots and the state could also be seen in ACWF’s announcement of its agenda to include sanitary goods in the list of official emergency provisions (Huang 2020). The resistance against this instance of feminist activism was not from the state, but from anti-feminism networks on Weibo. These male bloggers attacked Liang and female volunteers for their high-profile campaign highlighting women’s rights, which, to them, equated with man-hating. Although their verbal attacks bothered women involved in the hashtag activism, they were not discouraged, as they received discursive and emotional support from numerous feminist bloggers fighting back against misogyny on Weibo.

Since the wide circulation of the hashtag, feminist activism on social media has put menstruation, or “the trifle under women’s pants” (a comment on Liang’s Weibo from a male blogger), on the table, and the donation of sanitary goods has even extended into a new campaign against menstruation-shaming. Various hashtag campaigns were launched on Weibo, such as # I’m a Woman and I Menstruate and # Menstruation Not Hidden to normalize the visibility of menstruation. Corporate powers, such as Libresses, also participated in and helped mainstream the campaign by exhibiting new commercials about sanitary pads under the slogan of “menstruation not hidden”. The blue water used in previous commercials, exposed by feminists as a symbol of menstrual blood taboo, was replaced with red.

The visibility of menstruation is significant because, for many, it represents the visibility of femaleness, thus the visibility of women. In the publicity surrounding medical workers fighting like macho soldiers in a battle against the virus, female medical workers could only be seen when wearing masculine masquerade. The power negotiations around women’s menstruation rested on the legitimacy of femininity in the masculine cause of fighting coronavirus. The related erasure of femininity led directly to the erasure of the contributions made by female medical workers, as shown in the all-male publicity of “anti-pandemic heroes” and state nominations of anti-pandemic heroes in which 20% male medical workers seized over 50% of awards. To restore femaleness, feminist bloggers on Weibo launched hashtag activism. They not only successfully collected donations for sanitary goods, but also disseminated feminist discourses to resist the period shaming of patriarchal culture. These numerous sporadic grassroot feminist activities were the pivotal power to reframe the gender dynamics in China during the Covid19. The binary categorization of gender that dominated both state and feminist discourse, however, should also prompt reflection in order to further feminist critique of gender essentialism in patriarchal society.

Fan Yang is a PhD candidate at the department of Media Studies at University of Amsterdam. Her research project focused on Chinese women’s cinema in the 21st century. Her current research interests include discursive trajectories of various feminisms in the People’s Republic of China, women’s cinema and discursive feminism on Chinese social media. Her most recent publication is “Post-feminism and Chick Flicks in China –Subjects, Discursive Origin and New Gender Norms” in Feminist Media Studies. Image credit: @梁钰stacey

- TV Drama Discourse on Stay-at-home Fathers in China: Super Dad & Super Kids - January 28, 2022

- Freud and China - January 20, 2022

- “Cultural China 2020″—A Different Take on China - January 7, 2022