Written by Marc Matten

For many decades, the visual arts have been a topic in research on modern Chinese history. Propaganda posters, Mao badges, and even material objects have received widespread attention among historians, thereby highlighting that an understanding of Mao-era China includes more than deciphering texts and comprehending their abstract rhetoric of exploitation, class struggle, and revolution. Propaganda posters, in particular, have been an object of desire, a desire that is sometimes shaped by a certain sense of orientalism, an identification with alternative models of society among activists during the Cold War, and sometimes by a morbid fascination with relics from the Cultural Revolution. Tourists in China acquire reprints as souvenirs, collectors produce colourful catalogues, exhibitions are organized inside and outside of China, and iconic parts of posters are reproduced for merchandise articles, ranging from T-shirts to cups, from tote bags to fancy accessories.

Thanks to the long-term efforts of institutions such as the International Institute of Social History (Amsterdam, see here) and the University of Westminster’s China Visual Arts Project Archive (see here), thousands of posters have also been made available for academic research in historical science and visual arts, allowing in-depth research on the history of propaganda in twentieth-century China.

During the Mao era and especially in the Cultural Revolution propaganda posters were a central medium for political communication and could be seen virtually everywhere (to be sure, they were more present in cities than in the countryside). Following the guidelines for literature and art laid down in Mao Zedong’s well-known Talks at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art (Zai Yan’an wenyi zuotanhui shang de jianghua 在延安文艺座谈会上的讲话) dating from 1942, literature and art had to serve the masses of the people and reflect the ‘correct’ class standpoint. Art and literature were instrumental in the dissemination of the ‘right’ political consciousness, which also explains the unbroken continuity of propaganda from the 1940s until today.

Propaganda posters were, I argue, only one of many media that were at the disposal of the communist party-state. Next to newspapers, comics, films, and magazines that to various degrees relied on visual elements in disseminating political ideas, books played an important role. They were available in all sizes and paper qualities, printed in traditional or simplified characters, covering everything from belletristic literature and school textbooks to handbooks and manuals in science and technologies. The state promoted reading as access to knowledge in Mao-era China, and soon after 1949 reading in state-owned bookstores, in private spaces, and in libraries became a regular phenomenon, particularly among the urban population.

Books had, to be sure, a significant impact on the formation of political consciousness, yet this was not only achieved by their textual message. Publisher and readers paid particular attention to book covers whose graphic design and aesthetics changed after the founding of the PRC in 1949 when their visual language recombined the folk-art traditions that had been established during the Yan’an years with the graphic style from the Soviet Union and other countries of the Eastern bloc that were entering China by the rapidly growing number of translations.

The following book covers differ accordingly.

The 1951 booklet Invasion by Hollywood (Haolaiwu de qinlüe 好莱坞的侵略) – a collection of articles denouncing movies and American influence on movies — is a compilation of translated newspaper articles by David Piatt, an American communist film critic, and texts by Chinese authors pointing to what they described as the brutal and savage, as well as anti-social and anti-human character of Hollywood movies. The motive and design of the book cover imitate earlier ones from the Republican era.

Invasion by Hollywood (1951). Image from the author.

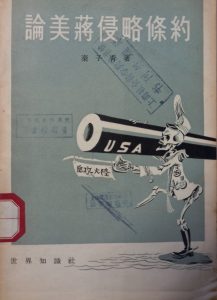

The 1955 book Discussing the Invasion Pact of the United States and Chiang Kai-shek (Lun Mei-Jiang qinlüe tiaoyue 论美蒋侵略条约) is a short, yet dense booklet of 48 pages written by Qin Ziqing 秦子青. Across six chapters, it describes how Chiang Kai-shek and John Foster Dulles concluded the Sino-American Mutual Defense Treaty (considered by the author as illegal), and how the Chinese people would reject it due to their unshaken will to liberate Taiwan. The cover shows a caricature of a skeleton whose insignias show that it is Chiang who declares an attack on the mainland. The style of the caricature is a continuation from the satirical journal World Knowledge (Shije zhishi 世界知识) that the same company had been publishing in the Republican era.

Discussing the Invasion Pact of the United States and Chiang Kai-shek (1955). Image from the author.

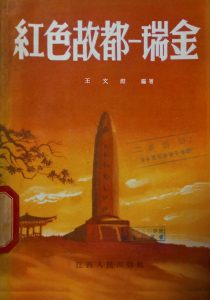

The book The Red Former Capital—Ruijin (Hongse gudu—Ruijin 红色故都-瑞金, 1958) by Wang Wenyuan 王文渊 describes the establishment of the first Soviet on Chinese soil in Ruijin. The narrative is supplemented with photos and maps. The cover itself reproduces the iconic stele commemorating the martyrs of the Red Army (Hongjun lishi jinianta 红军烈士纪念塔), choosing red as the primary colour, thereby conforming to the colourful style of socialist realism.

The Red Former Capital—Ruijin (1958). Image from the author.

The publication entitled Doing Everything to Strengthen the Dictatorship of the Proletariat (Yiqie weile gonggu wuchan jieji zhuanzheng 一切为了巩固无产阶级专政)—printed at the end of the Cultural Revolution (1966-76)—praises two traffic policemen who had made great sacrifices in their work, even at their own risk of injury, to serve the people and apprehend the criminal class enemy. Though mono-coloured and drawn in a simple fashion, it underlines the assertiveness of the policemen on their speedy motorbike.

Doing Everything to Strengthen the Dictatorship of the Proletariat (1975). Image from the author.

The book covers presented above stem from one of the largest book collections of the Mao era in Germany, a donation of the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences (SASS) to the Friedrich-Alexander University of Erlangen-Nuremberg (FAU). In the early 2000s, the Academy had to sort out its duplicates, amounting to close to 100,000 monographs and roughly 10,000 bounded volumes of periodicals, all published from the late 1940s to the 1980s.

The openly accessible SASS collection features an assortment of publications ranging from translated Marxist classics to medical textbooks, from philosophical and literary works to agriculture handbooks and propaganda pamphlets, from popular youth magazines to academic journals. It also includes numerous ‘internal publications’ (neibu 内部) across all book categories. The largest categories are science and technology (19,000 volumes), economics, industry, agriculture, and commerce (15,000 volumes), history and historical science (11,000 volumes), as well as literature and arts (14,000 volumes).

The collection houses a large number of books on engineering (with blueprints of machines), geology, medicine, astronomy, veterinary medicine, etc. Researchers of history may trace the anti-Japanese sentiment in current China back to the publications on the Anti-Japanese War (1937-45) in the 1950s and the 1960s. They can also feel the political climate of the early PRC by looking at publications demanding the liberation of Taiwan in the mid-1950s or the preceding Korean War. Internal publications highlight the ‘anti-Chinese expressions’ of the Soviet Communist Party and of Eastern European countries (e.g. Czechoslovakia), as well as detailed studies on criminal forensics and overviews on the status of nuclear physics research in the United States and Europe in the 1950-60s.

For researchers in the field of cultural studies, the collection offers materials in Chinese and foreign literature, theatre, film, and music. The materials on the perennial campaign of ‘Learning from Lei Feng’ display an impressive variety as oral performance (music/lyric, traditional opera scripts, bamboo clapper talk), textual narrative (his diary, poems on Lei Feng, children’s story, movie script) as well as picture albums. The abundance of scripts of drama and opera in the 1950s and 1960s can be used for investigating the modernizing/propagandizing process of these genres as well as their role in promoting the ideas of patriotism, class struggle, revolutionary spirit, and socialist construction in the first decades of the PRC, which offers new insights in the cultural life, especially for the 1960s and 1970s.

Complete sets of journals such as World Knowledge (Shijie zhishi 世界知识, Knowledge is Power (Zhishi jiu shi liliang 知识就是力量), People’s Liberation Army Pictorial (jiefangjun huabao解放军画报), Chinese Agricultural Science (Zhongguo nongye kexue 中国农业科学), Soviet Agricultural Science (Sulian nongye kexue 苏联农业科学), or Artefacts of the Revolution (Geming wenwu 革命文物), to name just a few, offer information on a whole array of topics.

The collection is accessible to researchers and Ph.D. candidates. Due to its size, a catalogue is not available (yet), but a first impression of what is available can be gained by having a look at the bookshelves. Inquiries can be sent to Marc Matten, marc.matten[at]fau.de.

Marc Matten is a professor for contemporary Chinese history at Friedrich-Alexander University of Erlangen-Nuremberg (FAU) in Germany. He is working on the legacy of the Maoist past in contemporary Chinese society, as well as recent developments of global historiography at Chinese universities.

- TV Drama Discourse on Stay-at-home Fathers in China: Super Dad & Super Kids - January 28, 2022

- Freud and China - January 20, 2022

- “Cultural China 2020″—A Different Take on China - January 7, 2022

Super