By Caroline Fielder

China has enjoyed a long and rich history of religious charity and philanthropy with some of the earliest forms of Chinese charity inspired by Confucian, Buddhist and Daoist teachings promoting the values of benevolence and compassion and focused on mutual assistance and charitable giving between kinship lines. Since the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, however, both religion and charity became viewed with suspicion and over time events and practices waned until the mid-late 1980s when it became possible once again for religiously inspired organisations to become involved in social welfare and development work. A decade later, following deliberate efforts by the state to rehabilitate the concept of charity within wider society, religiously inspired charitable organisations (RICOs) began to re-emerge in earnest.

Today, after a period of marginalisation, we can see that religious charities from a number of traditions are once again on the rise. This year’s annual charity fundraising event held by Chinese internet giant Tencent (the ‘Tencent 99 Giving Day’) saw the Nanjing-based RICO, the Amity Foundation, become it’s 10th biggest beneficiary. Given that religion and charity have been sensitive spheres of influence in China’s recent history and have therefore been tightly managed, the exposure given by the event was doubtless extremely meaningful in bringing Amity’s work, its vision and mission to the fore of the general public’s imagination. The 435 projects that Amity put forward for support must have resonated with a lot of individual donors as they managed to raise a total of almost 66,520,000 RMB (approximately £7.3 million) over the course of three days.

For any organisation this would be considered a major success, but as one considers Amity’s religious heritage it is worth spending a moment asking what the rise of Amity, and the emergence of the wider RICO sector, can teach us about contemporary Chinese society. Scholars like Durkheim and Troeltsch have long-since argued that religion can mirror wider society and I would suggest that RICOs such as Amity present us with a particularly interesting lens through which to explore developments in wider Chinese society.

Church in rural Guizhou. Image credit: author

Firstly, as organisations created at a specific time and for a specific purpose, their very existence, organisational values and ideals can help us appreciate changes in Chinese society, including shifts in rhetoric, modifications in social behaviour, and changes in political focus. The growing presence of RICOs in wider society reflects a much-changed social and political reality compared to that of the 1950s to early 1980s, when both charity and religion were viewed with suspicion. Charity, once seen as a marker of a feudal society and a means of keeping the poor in their place is now no longer seen as a challenge to the Party or a critique on its ability to provide for its citizens. Similarly, although differing voices can still be heard, religion has morphed from being viewed as a ‘drug’ which should be eradicated, to a ‘medicine’ with the potential to bring about social stability and provide healing for the nation. Christianity, previously viewed with disdain, as summed up in the old adage ‘One more Christian, one less Chinese’ (duole yige jidutu, shaole yige zhongguo ren), has seen a considerable change in fortunes since the period of reform and opening up. A renewed openness in both policy circles and society has allowed for Christianity to now be seen by some as a potentially progressive force with a distinctive and growing Chinese voice.

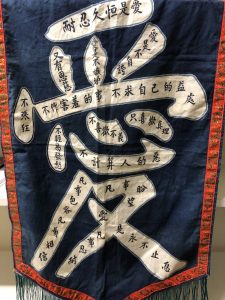

From the outset Amity has taken a lead in challenging stereotypes and initiating positive forms of dialogue between religious groups and wider society, including those outside China. In Chinese its name is made from two characters ‘Ai de’ meaning love and virtue (or virtuous deeds). In 1984 one of the founding fathers of the organisation, Bishop KH Ting, wrote a letter to international friends where he laid out his vision for Amity to be an organisation which promoted love and virtuous deeds, emphasising the positive contribution of Chinese Christians to society. No longer should they be seen as foreign lackeys or traitors, instead Amity would be a vehicle for Chinese Christians to come together to do their part ‘as citizens in nation-building’ in order to ‘make the fact of Christian presence and participation better known to our people, without in any way weakening the work of the church proper’ (see Amity Foundation).

The Beatitudes written within the character for ‘ai’, meaning love. Image credit: author

Established formally in 1985, the Amity Foundation has grown from a three-man organisation with limited resources to a multi-million-pound foundation, headed by a woman and which now serves as an incubator to aspiring young charities within the wider sector. Since its inception Amity’s work priorities have echoed and reinforced patterns from wider Chinese society. These include a mirroring of the reform and opening process through the re-establishment of links with international ‘friends’ in the 1980s (including the establishment of a new model for overseas relationships which focused on people-to-people sharing based on mutual respect, comprising an understanding of the changing realities of local church life rooted in new China and led by Chinese); a focus on social changes and the need to mitigate against growing inequality within Chinese society through the rehabilitation of charity within Chinese society in the 1990s (taking up the call to ‘Go West’; facilitating technical knowledge exchange and the sharing of best practice with grassroots communities within impoverished sectors of Chinese society; building trust across social divides and channelling funds and help to where they were most needed); building social resilience in the 2000s, including the rebuilding of communities following a number of natural disasters, and recognising the need to develop a Chinese funding base so as to become more self-sufficient (the financial crisis had a big impact as 98% of project funding still came from overseas in 2008); and undertaking a process of internationalisation in the 2010s (acting as a conduit for Chinese volunteers going overseas, and the transmission of Chinese ideas of development and charity to the world through the opening of Amity offices in Ethiopia in 2015, in Geneva in 2017, and in Kenya in 2019).

Alongside this mirroring of social changes, RICOs such as Amity have also acted in the cognitive sense of allowing society to see itself, and in that process to become more self-conscious and open to change. As such it has more subtly served as a catalyst of socio-cultural change. In a society which has sought to privatise religious thought and confine religious activities to within the physical walls of religious institutions, such as churches, temples and mosques, RICOs have sought to extend religion’s scope by taking it’s work firmly into the public sphere and working with faith communities and those with no religious belief. The process of taking religion into the public sphere has not only been a challenge to forces in support of secularisation but also questions more conservative elements from within the church who see charity, social welfare and development as the work of the state, and criticise RICOs for diverting important resources away from what they see as ‘real’ religious work. Such challenges enhance the fluid and dynamic cultural role of religion, extending it beyond the confines of its more traditional institutional embodiment.

Free clinic for the elderly. Image credit: author

In many ways the appeal of the Amity Foundation is simple and lies in its ability to connect people and to build trust across communities, religious and ethnic divides. It is also in its ability to present a form of religion which echoes Bellah’s notion of a civic religion – drawing inspiration from a particular religious tradition, in Amity’s case working alongside Protestant churches both inside China and globally, and yet at the same time being independent of those same churches or indeed any other recognised religious institution. As such Amity draws on particular teachings and yet remains religiously ‘distinctive’, and as such is able to develop its own character and sense of integrity. Not being rooted in the church structures and hierarchies frees it from many political and doctrinal constraints and broadens its appeal to wider sectors of society.

This more nebulous, non-doctrinal approach does not necessarily align with organized religion but should not be seen as a weakening or a rejection of religious values. As its popularity in recent fundraising events also shows, this form of religious expression arguably has an appeal to wider sectors of society who themselves are more fluid and questioning in their approach to religious and other issues of concern. RICOs such as Amity are increasingly becoming a more active and vocal sector of society, not just within China but now also internationally. As such these organisations, which have historically had relatively little attention paid to them, deserve to be much better understood and scrutinised.

Caroline Fielder is a lecturer in Chinese Studies within the School of Languages, Cultures and Societies at the University of Leeds. Her current research explores the changing role of religion in Chinese society, focusing on the increasingly visible role of Chinese religiously inspired charitable organisations. She is currently working on a monograph ‘Taking giving seriously: understanding the re-emergence of religiously inspired charity in contemporary China’. Image credit: 风之清扬.

- TV Drama Discourse on Stay-at-home Fathers in China: Super Dad & Super Kids - January 28, 2022

- Freud and China - January 20, 2022

- “Cultural China 2020″—A Different Take on China - January 7, 2022