Written by Anne Witchard

The artist and writer Chiang Yee is best remembered for his Silent Traveller books, a series of illustrated travelogues that presented Anglophone readers with a Chinese perspective on familiar destinations. Informative, thought provoking and humorous, they found a wide readership and are still enjoyed today. Chiang Yee’s contribution to the art of ballet however is quite overlooked, perhaps because – as it turned out – it was a one off. But it is an episode that has much to tell us about his artistic versatility and about his wider significance to British cultural life.

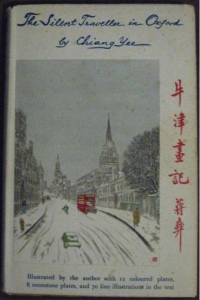

After his Hampstead home was destroyed in the Blitz, Chiang Yee relocated to Southmoor Road, Oxford (Blue Plaque) where he would reside for the next fifteen years. In the penultimate chapter of The Silent Traveller in Oxford, titled ‘Friday the Thirteenth, he describes the woes of the London commute and bewails the inadequacies of the train system, erratic no doubt due to the exigencies of wartime rather than because on this particular day, as an old lady points out to him, it is Friday the Thirteenth.

Chiang Yee had become something of a regular commuter because he had been commissioned to design a new ballet, The Birds. And, as he explains: ‘There seemed perpetually to be some detail or other for which my attendance was required – some costumes had been finished and were to be fitted, or certain materials that I had chosen had proved unobtainable and others must be selected. And always the matter was urgent. No time to be lost’.

He had been appointed by Constant Lambert, the celebrated conductor with Ninette de Valois’ recently formed Sadlers Wells company, a great gathering point for artists which, after a passionate wave of wartime patriotism would emerge as the Royal Ballet. Lambert was a remarkable man, something of a Sinophile and in order to appreciate his choice of Chiang Yee, it is important to recognise the significance of a British national ballet at this time – and Lambert’s part in establishing it.

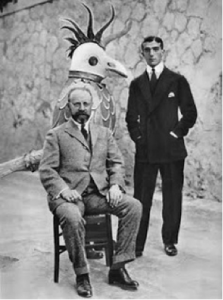

Until the arrival of Sergei Diaghilev’s ground breaking Ballets Russes in 1910, ballet on the British stage had been an amateur affair. The effect of the Ballets Russes was to raise the status of British ballet from a rather risqué music-hall entertainment, frequented mostly by men, to an artistically respectable art form. Unlikely as it might seem, the conditions of the second World War were to prove the hotbed in which the young seedling of British ballet grew to maturity and to popularity. Soldiers on leave eagerly swelled the regular audience and the dancers’ reputations grew from minority cult to star status. It seems likely that one reason for Constant Lambert’s wish for The Birds to be given a Chinese design was a nod to the various Ballets Russes productions of The Nightingale, based on Hans Christian Andersen’s chinoiserie fairy tale, ‘The Emperor’s Nightingale’ composed by Igor Stravinsky.

Diaghilev had always employed the most cutting-edge artists rather than theatre designers to work on his ballets, and in asking Chiang Yee to design The Birds, Lambert (who had worked with Diaghilev) was following suit.

Leonide Massine and Henri Matisse (seated) with his costume for the mechanical nightingale in Le chant du rossignol (debut February 2, 1920)

The lesson Lambert learned above all from Diaghilev was that ballet could be an intoxicating creation in which dance, music and design are one. The Birds was a brand new ballet choreographed by Robert Helpmann to showcase the talents of the company’s up-and-coming young ballerina, fifteen-year old Beryl Grey. Elaborate feathered costumes required frequent trips to London at short notice. Chiang Yee, we learn, managed to get to his rendezvous on time despite it being Friday the 13th and he goes on to describe the fittings. He arrived at the studio of costumier Matilda Etches to find Helpmann attempting “to put on his head the tail-piece of the male dove’s costume, which was fan-like and looked, on him, like a Red Indian’s feathered head-dress”.

Beryl Gray as The Nightingale

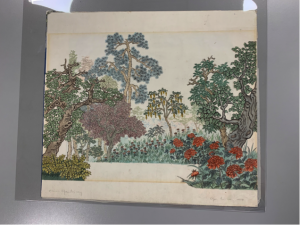

Costume Design for Male Dove

Reviews of the ballet were mixed and suggest that the design was its strongest suit – The Dancing Times described its “ravishing garden setting and charming costumes”. Horace Horsnell in The Observer 29, 1942 loved its pretty “animated chinoiserie”, writing “The birds … are delightfully dressed by Chiang Yee, and roost, one feels, not in his decorative wallpaper trees but in cabinets of rare porcelain.” Elspeth Grant in the Daily Sketch, November 25, 1942 called it “light, sweet, delicious,” and James Redfern, The Spectator, November 27, 1942. found it “an entrancing ballet” with a “rewardingly complete unity of style in music, choreography and decor”.

“the trees are chiefly of a peculiarly vivid green & the flowers large & red. These various plant forms are slightly conventionalised but are treated in a detail which verges on the practice of the pre-Raphaelites” Bradley’s Ballet Bulletin

Chiang Yee’s costume and set designs are stored in the archive of the Royal Opera House.

Anne Witchard is a Reader in English Literature and Cultural Studies at the University of Westminster. She is a leading scholar in the studies of Sino-British connections in modern literature. Her publications include Thomas Burke’s Dark Chinoiserie: Limehouse Nights and the Queer Spell of Chinatown (Ashgate, 2007), Lao She in London (Hong Kong University Press, 2012) and England’s Yellow Peril: Sinophobia and the Great War (Penguin, 2014). She is editor of London Gothic: Place, Space and the Gothic Imagination (with Lawrence Phillips) (Continuum, 2010) and Modernism and British Chinoiserie (Edinburgh University Press, 2015). Featured image: Dove and Nightingale with Attendant Doves and Sparrows.

- TV Drama Discourse on Stay-at-home Fathers in China: Super Dad & Super Kids - January 28, 2022

- Freud and China - January 20, 2022

- “Cultural China 2020″—A Different Take on China - January 7, 2022