Written by Jian Xu and Elaine Jeffreys

The Covid-19 pandemic provides a remarkable context and compelling case for thinking about celebrity politics in China. International celebrities have played an important role in poverty alleviation and disaster-relief efforts historically. Yet celebrity humanitarianism is often criticised as a “self-serving” personal branding exercise that promotes “neoliberal capitalism” and perpetuates “global inequality”.

Celebrity humanitarianism has attracted major media and public attention in the context of the global Covid-19 pandemic. The most notable instance is perhaps the all-star “One World: Together at Home” virtual concert organised by popstar Lady Gaga in April 2020. The concert raised US$127 million for the World Health Organisation and its coronavirus response efforts. Around the same time, Madonna attracted negative publicity for describing the pandemic as a “great equalizer”, while sitting in a bathtub filled with rose petals.

Celebrity responses to Covid-19 in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) have attracted a wave of public support and a tsunami of criticism on social media. Singer Han Hong, founder of the Han Hong Love Charity Foundation, became a national heroine for raising over US$19 million in donations from hundreds of celebrities to support healthcare efforts in Wuhan – the original epicentre of the coronavirus outbreak. However, many other celebrities have been accused of lacking patriotism and social responsibility, as we explain below.

Han Hong philanthropy. Image source

What do online discussions of PRC celebrities in the Covid-19 context reveal about celebrity-government-public relations and celebrity politics in China?

Disgruntled netizens immediately started questioning the patriotism of celebrities as national public figures because some celebrities had left or allegedly “deserted” China at the start of the coronavirus outbreak. In late January 2020, the PRC government called on Chinese citizens to quarantine themselves or self-isolate at home during the lunar New Year holidays. Yet many celebrities had travelled overseas with families or friends around the same time, and were accused of trying to escape the virus. Some celebrities, including actors Lu Yi and Xiang Zuo and singer Yang Chaoyue, posted their vacation photographs while expressing support for people living in Wuhan on their Twitter-like Weibo accounts. Their actions sparked an online outcry from fans and other interested audiences quarantined in China.

The online criticisms increased in scale when netizens started posting photographs taken at airports of alleged “celebrity deserters” returning to China as the pandemic escalated overseas and the domestic situation improved. Such celebrities, including singers Cai Xukun, Han Geng and Wu Yifan, were negatively contrasted with Han Hong, who had stayed at home and raised money to assist the medical workers who were saving people’s lives at the risk of losing their own. Netizens condemned the celebrities who had left and then returned to China as “renegades” and “traitors”, whereas Han was upheld as a patriot and good social role model, and called for a ban on the public dissemination of products and performances associated with the so-called traitors.

Online outcry subsequently centred on the question of whether celebrities’ donations to the Covid-19 response matched their sky-high salaries. Netizens compiled a list of celebrity donors, ranking them according to the extent of their donations. The Weibo accounts of celebrities who were identified as not donating, or not donating enough, were then bombarded with posts accusing them of “donation stinginess”. Such criticisms replicated public complaints about the perceived limited nature of celebrity donations when compared to their astronomical salaries following the2008 Sichuan Earthquake. They also reiterated public criticisms of high celebrity salaries when compared to the salaries of ordinary Chinese workers surrounding the 2018 Fan Bingbing tax evasion scandal. Celebrity salaries became a renewed hot topic in the coronavirus context as netizens rebuked super-rich stars for failing to support China and the Chinese people through publicised donations in a time of national crisis.

Online calls for cuts to celebrity salaries, and higher salaries and public esteem for professionals in medicine and the sciences, coalesced around the slogan “Celebrities can’t save the country”. Professor Li Lanjuan, a Chinese epidemiologist who is regarded as a Covid-19 heroine, coined this slogan during a press interview. She said, “I hope that after the pandemic, the government will give high salaries to frontline scientists … Celebrities can’t make our country stronger … The prosperity of [China] doesn’t depend on celebrities, but rather on the talented people in science, education and medicine”. In other words, celebrities are overvalued; their failure to “step up” at a time of national crisis shows they do not deserve the income derived from public acclaim.

China’s anti-coronavirus heroine, Li Lanjuan. Image source

The recent expansion of formal controls over the PRC’s celebrity and entertainment industries, and the political importance of online public sentiment, adds weight to what might otherwise be viewed as simply “sour grape” criticisms. In October 2014, President Xi Jinping delivered a speech stating that literature and arts should promote “core socialist values”, be creative and people-orientated, and serve the political agenda of the Chinese Communist Party. Artists and cultural workers are expected to pursue “professional excellence and moral integrity” (deyi shuangxin), an ideal that the Communist Party has promoted since the Mao era. However, Xi’s speech was followed by new regulatory initiatives designed to promote professional ethics and social responsibility in the entertainment industries. The PRC’s first Film Industry Promotion Law of 2017, for example, stipulates that actors, directors and other persons in film should uphold virtue and art, comply with laws and regulations, respect social morality, abide by professional ethics, adopt self-discipline measures, and establish a positive social image. Regulations issued in 2014 enjoined film, television and radio employees to disseminate “positive energy” by providing excellent products and presenting a good public image, and banned the appearance on broadcasting platforms of “misdeed artists”, that is, actors, directors and screenwriters convicted by the public security forces for engaging in drug, prostitution or other offences.

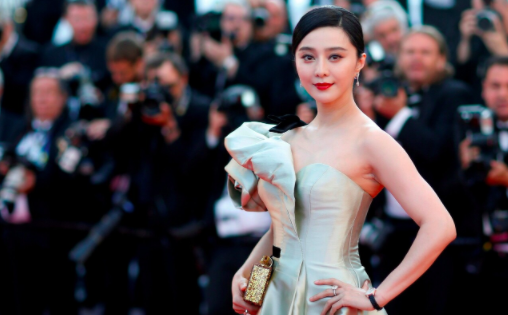

Government demands that celebrities display a positive social persona in exchange for a continuing career are reinforced by similar public expectations. The tax evasion scandal associated with Fan Bingbing, once China’s highest-paid movie star, is a case in point. Online outcry over Fan’s alleged use of “yin-yang contracts” to evade tax, and thus failure to meet her citizen obligations, prompted a government investigation and resulted in Fan being ordered to pay US$129 million in late and evaded taxes. The National Radio and Television Administration (NRTA) then issued a Notice recommending major pay cuts for radio and television stars. The strength of public condemnation has ensured that efforts by Fan to re-establish her online presence have not been received positively to date. Public anger over the perceived failure of high income-earners to “give back” to society has been reignited in the Covid-19 context because many people have lost their jobs or had their salaries reduced.

Fan Bingbing. Image source

The dual exercise of top-down government regulation and bottom-up online public supervision ensures that China’s celebrities have inherent “star vulnerability” rather than “star power”. Scholars of celebrity politics in western societies have variously refuted the argument that celebrities are a “powerless elite” because they have limited access to real institutional and political power. Instead, they contend that contemporary celebrities have economic and social power that extends to the political realm because they can influence audiences and political agendas through media publicity, especially given the mediatisation of western democratic politics. In contrast, the PRC’s legacy of state controls over mass media entertainment and promotion of socialist role models has ensured that even contemporary celebrities are expected to promote government policy agendas. This expectation is being reinforced not only though regulatory frameworks, but also through the informal means provided by digitally equipped netizens – fans, anti-fans and other interested audiences – who are keen to supervise celebrity behaviours.

Jian Xu is a Lecturer in Communication in the School of Communication and Creative Arts, Deakin University. He researches Chinese media and communication with a particular focus on Chinese social media, digital youth cultures and celebrities. He is the author of Media Events in Web 2.0 China: Interventions of Online Activism and co-editor of Chinese Social Media: Social, Cultural and Political Implications.

Elaine Jeffreys is Professor in International Studies, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Technology Sydney. Recent publications include: Governing HIV in China; New Mentalities of Government in China; Sex in China; and Celebrity Philanthropy.

- TV Drama Discourse on Stay-at-home Fathers in China: Super Dad & Super Kids - January 28, 2022

- Freud and China - January 20, 2022

- “Cultural China 2020″—A Different Take on China - January 7, 2022