Written by Orna Naftali

War culture has had tremendous power in shaping modern understandings of the nation in the PRC. But the role of children’s education in the creation of that culture has received little attention. Most studies that have tackled this issue focus on media and literary works, and argue that in Maoist publications, youth were typically portrayed as ‘small soldiers’ – a trope that all but supplanted both indigenous, Confucian notions of children as incomplete human beings and modern, romantic images of the ‘innocent child’ introduced from the West in the first half of the twentieth century. This claim echoes that of scholars who have looked at Cold War cultures elsewhere in the world and argue that in countries of the Eastern Bloc, children were accorded more aggressive roles than in the West, where the myth of the ‘defenceless child’ predominated mainstream culture. In a recent article in the Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth, I challenge this assumption by highlighting the complex nature of the discourse about children, youth, and political violence in Maoist era China.[1]

The roots of modern Chinese debates about the role of children in military struggle can be traced to the first half of the twentieth century. Most scholars (see, e.g., Farquhar 1999; Donald 2005; de Giorgi 2014; Kauffman 2020; Zheng 2021) nonetheless maintain that the promotion of children’s engagement against foreign and domestic enemies in the 1930s-1940s opened the way for a full-scale militarization of childhood in the Mao era. My study elaborates on this thesis by examining war narratives in PRC middle school history textbooks and discussions about ‘war education’ in general media publications and pedagogical journals of the 1950s-1970s.

My analysis reveals the existence of conflicting ideas of childhood and military aggression throughout the period in question. In the 1950s, PRC education journals conveyed the notion that children should be taught about the politics of war if they are to be trained for their role as future revolutionary fighters (see, e.g., Fig. 1). Yet, educators did not necessarily cast youngsters in the role of ‘small soldiers.’ During the Korean War (1951-53), for instance, children’s publications sought to teach students to ‘hate the US imperialists’ and ‘beat American arrogance’ However, some educators argued that exposing children of all ages to information about American ‘military atrocities’ could weaken children’s characters and willingness to fight, thereby damaging their sense of national pride. Others promoted a view of childhood couched in developmental psychology, according to which children are more vulnerable emotionally and therefore must not become involved in—or exposed to—information about war brutality. Accordingly, the middle school history textbook used in Chinese schools of the 1950s described war as the business of adults. It portrayed youth as victims of political conflict rather than as active fighters, and avoided graphic depictions of military violence.

Fig. 1: Cover of Xiao pengyou 小朋友 [Little Friends] magazine, No. 1010, May 10, 1951.

These features can be explained by the fact that in the early years of the PRC, the field of children’s education was still led and populated by Republican-era intellectuals, who may have adopted the socialist notion of children as political agents, but held to imported liberal and psychologized notions of childhood innocence or indigenous, Confucian perceptions of children as ‘incomplete’ human beings. That said, a conflicted view of children and violence was evident in subsequent decades as well, even as Chinese society became more militarized.

The early 1960s witnessed a shift in the way PRC thinkers regarded war education, a transformation that can be traced to broader developments in both the global and domestic arenas. As China became involved in a border war in India and was preparing for a potential conflict with US forces in Vietnam in the south and the Soviet Union in the north, Mao Zedong was also concerned that policies issued by the CCP after the debacle of the Great Leap Forward (1958–1961) exhibited signs of ‘Soviet revisionism’. To counter this trend, Mao launched a ‘socialist education program’ (1963), which employed military models to reintroduce ‘collectivism, patriotism and socialism’ into Chinese society and schools. The middle school history textbook of this period included lengthier, more detailed discussions of military violence, while highlighting historical incidents in which youth were said to take part in the fight against domestic and external enemies. Nonetheless, the early 1960s book consigned youth auxiliary roles such as fetching food and water for adult combatants.

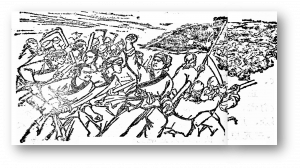

The launch of the Cultural Revolution (CR) in 1966 brought adolescents to the forefront of domestic political struggle in a very real sense. Textbooks produced during this period correspondingly highlighted the leading role of youth in military fighting. For instance, a 1973 book describes a scene during the first Opium War (1839–1842), in which British soldiers allegedly ‘escaped in shame’ and ‘knelt on the ground begging for mercy’ from Chinese adult and ‘youth’ (shaonian 少年) militia forces (see Fig. 2). Notably, depictions of the same scene in the 1950s textbook did not mention youth at all, while the 1960s version produced prior to the CR assigned youth a much less active role in the fighting.

Fig. 2: ‘San yuan li renmin kang ying douzheng 三元里人民的抗英斗争‘ [The people’s struggle against Britain at San yuan li]. Zhongguo Lishi, di er ce 中国历史第二册 [Chinese History, Vol. 2] (Henan Province: 1973), pp. 5-6.

Even as the ‘small soldier’ trope was rigorously promoted in CR textbooks, it would be wrong to extrapolate that educators across the country necessarily embraced this view. Indeed, reprimands circulating in PRC media publications up to the mid-1970s warned against the ‘stubborn tendency’ of certain educators to ‘over-protect’ students of all ages from horrific war stories due to the ‘false notion of children’s innocence’. These admonitions indicate that a notion of childhood as a time of vulnerability lingered among some educators, even as Chinese teenagers participated in extreme acts of aggression against their teachers and other authority figures in the initial years of the Cultural Revolution.

These findings suggest that the idea of children and youth as ‘small soldiers’ was never an unstated, assumed truth in Maoist-era education. Instead, it constituted a locus of continual debate between disparate views of childhood, pedagogy, and violence. My research further illustrates that during the Cold War era, idealized and often conflicting notions of childhood maintained by educators in socialist countries such as China were not in fact very different from those found on the other side of the political divide.

Note

The term children refers here to persons aged between 6-18 years old (designated in modern Chinese as ertong 儿童), while ‘youth’ refers to those at the middle school stage (ages 12-18), often designated in modern Chinese as shaonian 少年.

Orna Naftali is Senior Lecturer in the Department of Asian Studies and Director of the Louis Frieberg Center for East Asian Studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Her main research interests include the anthropology of childhood and youth, education, gender, nationalism, and militarization in the PRC. She is the author of two books: Children, Rights, and Modernity in China: Raising Self-Governing Citizens (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), and Children in China (Polity Press, 2016). Featured image: Tomorrow I will be a defender of the territorial sky of the motherland (1956). Source: University of Westminster’s China Visual Arts Project.

- TV Drama Discourse on Stay-at-home Fathers in China: Super Dad & Super Kids - January 28, 2022

- Freud and China - January 20, 2022

- “Cultural China 2020″—A Different Take on China - January 7, 2022

[…] the first piece, Orna Naftali examines children and war education in the PRC during the Maoist era, showing the complex and […]