Written by Carl Kubler

Childhood in China is undergoing a revolution. On May 31, 2021, just a few years after ending the decades-old one-child policy (yihai zhengce 一孩政策) that had defined much of urban family planning from the 1980s until 2016, the Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party announced that in an effort to combat falling birth-rates, a new three-child policy (sanhai zhengce 三孩政策) would replace the existing limit of two children allowed per family. Also this year, new restrictions on online gaming for netizens under the age of 18 have erased millions in stock value from publicly traded gaming companies such as NetEase (Wangyi 网易) and Tencent (Tengxun 腾讯), as officials seek to curb gaming addictions among minors. A roughly contemporaneous crackdown on for-profit after-schooling tutoring for elementary and middle school students has made even larger waves as government authorities seek to reduce financial and mental health burdens on parents and children, cratering the share prices of private education firms such as New Oriental (Xin dong fang 新东方) and TAL Education (Hao wei lai 好未来) and leading many to wonder what changes are next in store for China’s youth.

Although the specifics of these policies are new, efforts to reimagine and remake Chinese childhood are not. Since at least the early twentieth century, Chinese thinkers and policymakers have framed the wellbeing of China’s children as a key litmus test for the health of the nation. ‘To understand the degree to which a particular culture is civilized,’ wrote leading intellectual Hu Shi 胡适 in 1929, ‘we must appraise…how it handles its children.’ Essayist Lu Xun 鲁迅 similarly implored Chinese audiences to ‘save the children’ in his 1919 Diary of a Madman (Kuangren riji 狂人日记), calling for a modern nation led by a community of future adults not yet schooled in feudal society’s cannibalistic ways. Recent historical scholarship has shown that such exhortations were more than just rhetoric, with a variety of educational programmes and social reforms aimed at improving children’s welfare taking shape over the first half of the twentieth century (Tillman 2018; Zarrow 2015).

As I have argued elsewhere (Kubler 2018), these exhortations took a dramatic new turn in the wake of the Second Sino-Japanese War, as Communist educators placed a new labour-oriented ideal of childhood at the centre of the nation’s modernizing project. Prior to the 1940s, Chinese intellectuals and educators had largely treated childhood as a protected sphere, which was putatively insulated from the harsher realities of adult life, but the devastation of war had both ruptured that insulation and made the reconstruction of the nation—with the full participation of all its citizens, regardless of their age or social station—a matter of existential importance. Just as productive labour had become what one historian calls a ‘condition of social citizenship’ in the first half of the twentieth century (Chen 2012), in the post-war years this criterion of inclusion trickled down to encompass children as well.

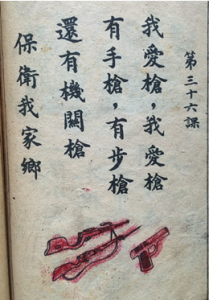

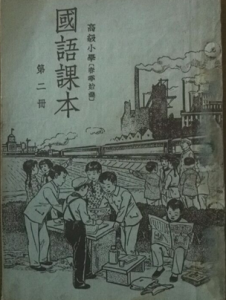

Visual media were particularly powerful in facilitating this inclusion and shaping children’s nascent worldviews. Lower-elementary literacy textbooks combined rhyming moral lessons about patriotism and national duty with striking images of children in adult roles—as farmers, soldiers, factory workers—and invited young readers to imagine themselves in service of the nation. ‘I love guns, I love guns,’ began one lesson. ‘There are pistols, rifles, and even machine guns; they protect my home.’ Many surviving textbooks from the era show that children actively coloured in the parts of the images that most resonated with them, while leaving other parts, like the bodies of enemy soldiers, devoid of colour.

Fig 1. Textbook illustration of children as soldiers, colored in by a child from Northeast China during the Second Sino-Japanese War. Source: Andong sheng jiaoyuting 安東省教育廳 [Andong Province Bureau of Education], Changshi: Chuji xiaoxue 常識. 初級小學 [General knowledge: Lower-elementary school] (1946, 1:35).

Fig 2. Rhyming lesson about children’s love of guns. Ibid., 1:36.

Fig 3. Textbook cover showing children in modern, adult roles. Gaoji xiaoxue Guoyu keben 高級小學國語課本 [Upper-elementary Mandarin textbook], vol. 2. 1951.

Historians of childhood have long debated the extent to which the concept of childhood, as a separate and protected sphere of social development, is a modern societal invention, as French medievalist Philippe Ariès controversially contended in the 1960s. Regardless of on which side of that debate one stands, however, recent developments have made clear that notions of childhood in China have continued to be reimagined and redefined into the present day. Although the construction of a modern Chinese nation may have lost much of the existential urgency that motivated societal changes in the mid-twentieth century, as Chinese policymakers envision new contours for state and society in the twenty-first century, the wellbeing and productivity of Chinese children remain inseparable from the wellbeing and productivity of the Chinese nation—and arguably even more so than before.

Carl Kubler is a Ph.D. candidate in modern Chinese history at the University of Chicago. His research interests include the history of childhood in twentieth-century China and the transnational dimensions of Qing socioeconomic history, with particular emphasis on the years immediately before and after the first Opium War. Featured Image: Who will get there first? 1980. Source: University of Westminster’s China Visual Arts Project.

- TV Drama Discourse on Stay-at-home Fathers in China: Super Dad & Super Kids - January 28, 2022

- Freud and China - January 20, 2022

- “Cultural China 2020″—A Different Take on China - January 7, 2022

[…] in this issue is a piece by Carl Kuber exploring the connections between ideas about childhood in the 1950s and more recent […]