Written by Ruichen Zhang

Visual culture in the People’s Republic of China features a rich collection of propaganda posters. With their unique visual style, language formation, and political messages, these posters are valuable for studying arts, social mobilization, and political persuasion across different periods in modern Chinese history. However, they are not just about the past. Indeed, these posters have also been variously revived in contemporary China in the form of memes across social media.

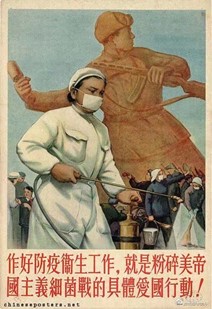

There are many examples of propaganda posters used as internet memes across a wide range of contexts. Just look at this poster in the header image. According to chineseposters.net, it originally comes from the Patriotic Health Campaign in 1952. The caption reads: ‘To do a good job in epidemic prevention and hygiene work is concrete patriotic behaviour in the battle to smash American imperialist germ warfare’ (作好防疫卫生工作,就是粉碎美帝国主义细菌战的具体爱国行动 zuo hao fangyi weisheng gong zuo, jiushi fensui mei diguo zhuyi xijun zhan de juti aiguo xingdong). I came across this image on WeChat from one of my friends’ ‘moments’ (朋友圈 pengyou quan). A Chinese postgraduate student studying abroad, he shared this image to complain about his roommates not paying enough attention to COVID and to express the importance of him staying alert and taking all necessary procedures to protect himself from COVID.

In recent years, repackaging propaganda posters in this way has become quite common on Chinese social media (see Zhang, 2020). It is essentially a mockery of the ‘red aesthetic’ which emphasises a unity of political ideology and everyday experiences (Donald, 2014), and more broadly, of the hypernormalised and formalistic rhetoric of the state. The gap often found between official rhetoric for political persuasion and multifarious everyday experiences can generate a particular type of ‘incongruity humour’, i.e. humour comprising two sharply contrasted elements to create effects of disappointment and tension relief (Monro, 1951). It is largely because of this incongruity that netizens have found remaking propaganda posters with contemporary captions to be particularly amusing.

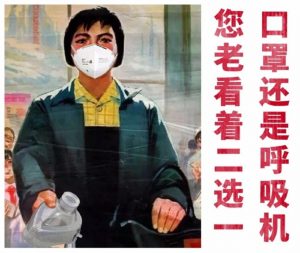

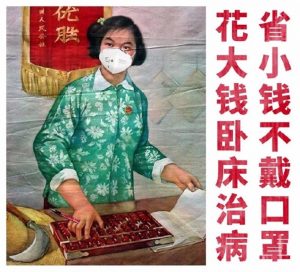

For example, at the early stage of coronavirus outbreak when many of the elderly in China refused to wear a face mask (see for example, Eckersley, 2020), young netizens decided to use propaganda posters to persuade them. On January 25th 2020, Weibo user @你丫才美工 (@yi ya cai meigong) shared 18 photoshopped propaganda posters to help netizens persuade their elder family members to wear a face mask. Among them, Image 1 says ‘Face mask or ventilator, you may need to choose one’ (口罩还是呼吸机,您老看着二选一 kouzhao haishi huxi ji, nin lao kanzhe er xuan yi). Image 2 goes ‘Save a penny for a face mask, you will spend a fortune lying in hospital’ (省小钱不戴口罩,花大钱卧床治病 sheng xiaoqian bu dai kouzhao, hua daqian wochuang zhi bing). While these memes were initially meant to persuade the elderly to wear masks by way of using posters that some young netizens thought might be both familiar and eye-catching, they were largely welcomed and in fact primarily consumed by young netizens themselves with laughter. It is hard to know to what extent elderly people found the repurposed posters to be in any way persuasive or how many even saw them, but we do know for sure that younger netizens found them extremely funny and that they quickly went viral on Weibo.

Image 1. Face mask or ventilator, you may need to choose one (credit to @你丫才美工)

Image 2. Save a penny for a face mask, you will spend a fortune lying in hospital (credit to @你丫才美工)

Propaganda posters repackaged as memes are also popular because they often imply a value contrast between collectivism and individualism. The posters above, for instance, attempt to persuade the elderly to wear a mask for their own good rather than for the country. By contrast, the 1952 epidemic poster above called for individual actions on disease prevention not because it was good for their own health, but because they were serving the country in doing so. A similar theme can be seen again in Image 3, where a soldier figure commonly seen in propaganda posters appears above the caption ‘I’m a socialist successor, I can’t be bothered with romance’ (我乃社会主义接班人,岂能谈儿女情长 wo nai shehui zhuyi jieban ren, qi neng tan ernü qing chang). While such expressions are now often used as a form of self-derogatory humour about being single, with the poster and socialist terminology used for further comic effect, it nevertheless points to a value contrast between prioritising ‘socialist construction’ and personal happiness.

Image 3. Socialist successors can’t be bothered with romance

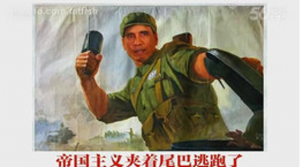

It is however important to note that the subversion of authoritarian rhetoric and aesthetic of persuasion by means of repackaging propaganda posters does not necessarily imply subversion of the values behind the rhetoric. While in some cases as in the memes above there is indeed a mockery of collectivism, in other cases repackaged memes are in fact promoting the very same values. For example, Image 4 captioned a soldier with ‘Imperialism fled away with its tail between legs’ (帝国主义夹着尾巴逃跑了 diguo zhuyi jia zhe weiba taopao le). Imperialist (which usually means western) countries are apparently the target of ridicule, which is consistent with the official rhetoric. It can be used for nationalist comments on news like the Sino-US trade war, or more generally as humorous complaints about foreign employers at work. Image 5 captions a poster of a woman being praised and applauded in a crowd with ‘Those who choose socialism are blessed with good luck’ (搞社会主义的人运气都不会太差 gao shehui zhuyi de ren yunqi dou bu hui tai cha). Commonly used for self-encouragement among young people struggling with studies or work, this meme may also imply some degree of approval of and identification with socialism.

Image 4. Imperialism fled away with its tail between legs

Image 5. Those who choose socialism are blessed with good luck

In most cases repackaged propaganda posters are not trying to promote any official political values at all. They are just a means of everyday self-expression on social media platforms. Image 6, for instance, jokes ‘Gain weight in holidays, lose weight in work’ (“假期里长的肉,用加班瘦回去”, jiaqi li zhang de rou, yong jiaban shou huiqu), while Image 7 says ‘C’mon! Let’s go argue with the production manager!’ (“走!和产品经理撕逼去”, zou, he chanpin jingli sibi qu). Here, these memes have little to do with the values of China’s political system, whether ironic, supportive or subversive. Propaganda posters here are simply used as meme templates for personalised connotations.

Image 6. Gain weight in holidays, lose weight in work

Image 7. C’mon! Let’s go argue with the production manager.

The fact that these ‘historical artefacts’ continue to have a social impact decades after they were first produced is not just about an interest in their ‘retro’ style, nostalgia for an imaginary past, or even about subverting the values promoted within, but, as we have seen, it is also closely related to broader terms and aesthetics of public discourse on the Chinese internet. Whether netizens agree with, disapprove of, or feel indifferent about the values behind official discourse, the repurposing of these posters must be understood as part of the everyday visual practices of netizens across Chinese social media and therefore must be carefully contextualised for nuanced analysis. From the creativity of these memes with their diverse meanings and uses, we can see how Chinese netizens are playing an active role in constructing public discourse in the age of participatory media.

Ruichen Zhang is a PhD candidate in Sociology at the University of Cambridge. She is working on digital humour and its socio-political implications in China and is more generally interested in power struggles and meaning making on the Chinese internet. She is co-editing a forthcoming special issue of AI & Society journal themed ‘Iteration as Persuasion in the Digital World’ with Dr. Clare Foster from CRASSH Cambridge.

- TV Drama Discourse on Stay-at-home Fathers in China: Super Dad & Super Kids - January 28, 2022

- Freud and China - January 20, 2022

- “Cultural China 2020″—A Different Take on China - January 7, 2022