Written by Coraline Jortay

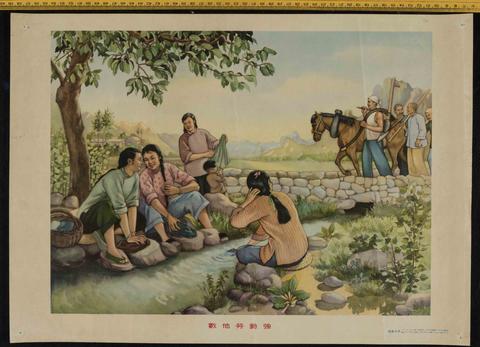

Let us consider for a minute this 1953 new-style New Year’s print (年画 nianhua) captioned “His labouring work is the best.” On a first level, the print was described by its contemporaries as representing women washing clothes in a creek and chatting, while admiring a rather strong fellow among a mutual-aid team of male labourers coming back from the fields. The image was said to embody women’s newfound freedom to contemplate better, self-determined marriage prospects under the new Marriage Law of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). On a second level, the visual tension between two kinds of labour (the men tending to the fields and the women washing clothes) present in the image is echoed in its caption through the archetypal characterization of the character 他 ta as “him”: his (the man’s) labour is the best, a question that ties back to what was considered “labour” (劳动 laodong), and what kind of women’s labour was valued in the early PRC and beyond.

What is interesting then, to the historian of Chinese language politics, is that the very linguistic underpinning upon which rests both of these levels of interpretation – 他 ta as meaning unequivocally ‘him’ in referring to a man – was merely thirty years old at the time. What is more, in 1953 pronouns were still the object of explicit party directives aimed at regulating how to ‘properly’ refer to men and women. Not only would this caption not have made much sense as recently as three decades earlier: this seemingly most mundane word (他 ta for ‘he,’ and only ‘he,’ with another differentiated pronoun for ‘she’) was the subject of heated debates throughout the Republican period and the early PRC – debates the crux of which was not too far removed from today’s questions of gender-inclusive language.

But let us rewind.

Prior to 1917, there was no third person feminine pronoun in Chinese as an unequivocal translational equivalent for “she.” In his 1933 Kaiming English Grammar, the great master of humour Lin Yutang discussed the colliding course that linguistic gender and social representations of gender could take in different societies:

It is strange also that, while the Chinese talk so much about sex distinctions (男女有別 nan nü you bie), they have not developed a distinction between he and she in their language, while the European people who talk so much about sexual equality should insist on this he-she distinction. The Chinese character for “she” (她 ta) dates back only to 1917.

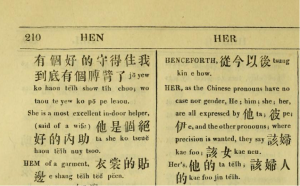

Of course, that is not to say that speakers did not have vastly nuanced ways of referring to a third person feminine prior to 1917, especially given the prominent importance of gendered terms of kinship and occupation which de facto functioned as pronouns in an open-ended lexical category. However, “pronouns” as a closed system of first/second/third person had not been an operational category prior to missionaries’ attempts at moulding the language onto the grammatical structures of Latin, English, or other languages which were most familiar to them. And indeed, the apparent “lack” of gender concord and clear-cut gendered pronouns bothered missionaries very much, as in apparent in the words of American missionary Arthur Smith in 1890 in Chinese Characteristics. Many bilingual dictionaries throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth century registered similar hesitations and colonialist hints at the view that Chinese would somehow be an “imprecise” language because linguistic gender functioned differently than it did in other languages (Image 1).

Image 1: Robert Morrison, A Dictionary of the Chinese Language, in Three Parts, Part III (Macao: Printed at the Honorable East India company’s press, 1822), 210.

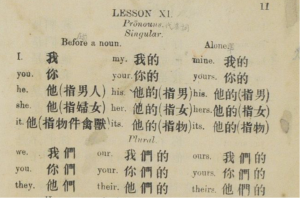

This view that linguistic gender was somehow “lacking” – and acutely so in the pronominal system – came to infuse the textbooks of a generation of educated children who would grow up to become prominent linguists and writers, the proponents of “new literature” and its Europeanized grammar in the May Fourth era. Image 2 shows the English textbook that Liu Bannong – the famed “inventor” of the Chinese character for “she” and a prominent linguist who first recorded the oscillatory patterns of tones of various topolects – used as a teenager to learn English. In this 1893 textbook, He, she, and it are translated using the same character, which is then followed by an explanation “[when] designating men,” “[when] designating women,” and “[when] designating things and beasts.”

As for the origins of “she” in Chinese, the story goes that Liu Bannong – facing difficulties translating fiction heavily laden with pronominal density – proposed the new pronoun during an editorial board meeting of New Youth as a way to forego recourse to expressions such as “this woman said” instead of “she said.” Other writers proposed a few alternatives of their own, some inflected with Japanese, some with Wu topolects, before new literature settled on using 她 as “she”. Recent research on the topic acknowledges some degree of opposition to the new pronoun, but concludes that “she” was quickly coopted on the road to “linguistic modernity,” especially by women writers keen to make use of a new visibilising tool amidst the centrality of the “woman question.”

Image 2 : C.D. Tenney, Yingwen Facheng 英文法程 [English Lessons], 1893, 11.

My research shows quite a different story: as early as 1920, a number of writers and activists were appalled by the hierarchies that the new set of gender-differentiated pronouns introduced in the language in the name of visibilising women. A frequent concern was that the “woman” radical on the left-handside of the pronoun (女 nü in 她 ta) introduced a pronominal hierarchy wherein men owned the “person” radical (亻ren in 他 ta, formerly a general third pronoun) while women were now “just women” and animals and things were “cows” (牜niu in 牠 ta). Many saw this pronominal hierarchy as intrinsically sexist, even asking whether marking linguistic gender was warranted at all. Anarcho-communist circles in the early 1920s rejected the masculine/feminine/neuter division and proposed their own “common gender” pronoun. Essayist Zhu Ziqing reported that girl students often crossed off the “person” radical in the new masculine pronoun, replacing it with a masculine (男 nan) out of spite. The notable novelist Cheng Zhanlu argued that gendering pronouns inevitably pigeonholed people who eschewed the gender binary such as eunuchs into a forcible “masculine” or “feminine.” So many more examples could be cited, from playwrights decrying having to deal with discrepancies between how pronouns were to be voiced (ta in all cases) and how they were written in scripts (differentiated pronouns) to poets such as Liu Dabai using alternative pronouns in poetry where gender-inclusivity or indeterminacy required so.

Meanwhile, as soon as the he/she/it pronominal split became mainstream in the periodical press in the late nineteen twenties, constructions akin to “he or she,” “she/he,” “(s)he,” or even concatenated plural forms such as here in the China Times started to appear. They effectively worked to re-introduce an inclusivity or ambiguity that was the norm barely fifteen years before. Many of these constructions lived in the periodical press throughout the 1930s and 1940s, although they always seem to have been the result of individual contributors’ linguistic politics rather than any widespread editorial policy. If quantitative corpus studies would be needed to ascertain exactly how widespread they were, they had gained enough ground by the early 1950s to warrant their own set of directives when the central government started calling for the “purification” of Chinese grammar and vocabulary, doing away with “excessive” Europeanized grammatical features. Programs for normalizing the written language were directly spearheaded by Mao’s aide Hu Qiaomu, leading to the compilation of Lü Shuxiang and Zhu Dexi’s 1952 Talks on Grammar and Rhetoric, which devotes an entire section to the question of “he and she.” The manual specifies that forms such as “he and she,” “he (she),” “he or she” and concatenated plural forms should be thoroughly banned, and that forms such as “men and women workers” (男女工人们 nan nü gongrenmen) could be used as substitutes when the context required that emphasis on women be made. The Talks on Grammar and Rhetoric went on to become the manual of prescribed style for normalizing all forms of writing for editors across the country.

In a similar fashion, in the lead-up to the drafting of the first Scheme for Simplifying Chinese Characters in the early 1950s, the possible re-simplification of gendered third-person pronouns into a single, pre-1917 gender-inclusive pronoun was debated, but in fine never materialized. When the First Table of Verified Allographs was jointly promulgated by the Commission of Chinese Script Reform and the Ministry of Culture in 1956, other gendered pronouns were abolished (the feminine second-person pronoun 妳 ni and the neuter third-person pronoun 牠 ta). Interestingly however, the masculine/feminine pronominal dichotomy had been deemed – despite all the initial pushback initiated in anarcho-communist circles in the early 1920s – a category useful enough for the young PRC to keep…

Through all of these debates, Chinese language politics invite us to rethink familiar debates of our time on pronouns and gender-inclusive writing, whether they concern the singular they in English, the interpunct in French, or the -x ending in Spanish. These very controversies, which we generally assume to be recent predominantly Western, battles (and perhaps a whim of late-twentieth and twenty-first century feminists?) effectively took place in China starting one century ago. In this regard, China’s pronominal feuds are illuminating: there, the gendering of pronouns and the pushback occurred over such a short period of time that no one could have argued that pronominal gender binaries were part of any “natural and immutable” law of the language.

Dr Coraline Jortay is a Wiener-Anspach Postdoctoral Fellow at the Oxford China Centre and a Junior Research Fellow of Wolfson College. She received her PhD from the Université libre de Bruxelles (ULB, Belgium) and is currently revising her dissertation “Pronominal Politics: (Un)Gendering Narrative and Framing Ambiguity in Chinese Literature, 1917-1937” into a monograph investigating the literary debates that followed the “invention” of gendered pronouns in Chinese. She recently co-edited a special issue of China Perspectives, Re-Envisioning Gender in China: (De)Legitimizing Gazes, and is more generally interested in gender and pronominal re-appropriations in twentieth and twenty-first century sinophone literature and translation. She is also a co-founder of the China Academic Network on Gender (CHANGE). Feature image credit: University of Westminster Archive.

- TV Drama Discourse on Stay-at-home Fathers in China: Super Dad & Super Kids - January 28, 2022

- Freud and China - January 20, 2022

- “Cultural China 2020″—A Different Take on China - January 7, 2022

I am a little confused about one aspect of this article. Am I right in understanding that the only gendered pronouns that have ever existed in any variety of Chinese are in the written language only or predominantly, i.e. that pronunciations of pronouns never or hardly ever varied according to the gender/sex of the referent?