Written by Jie Li

In what ways did cinema contribute to Mao’s personality cult? In their professional magazine Film Projection (Dianying fangying 電影放映), mobile projectionists often mention Mao’s appearance in newsreels as the greatest attraction for grassroots audiences. As a 1953 profile of a movie team from Guizhou put it:

When the masses learned that a film had Chairman Mao’s image, they were so excited they began dancing to celebrate the joyous event. A seventy-some-year-old man of Dong ethnicity ran with a torch to shout out the news to nearby villages: ‘Chairman Mao is coming! Everyone go look!’ The glad tidings of ‘Chairman Mao is coming’ soon spread so that thousands of people hurried over … A blind old man who heard the news asked his son to carry him through the mountains. He said: ‘I cannot see Chairman Mao, but I want to hear his voice.’

When Chairman Mao appeared in The Great Unity of Chinese Ethnicities, the site was filled with the sound of applause and shouting of ‘Long Live!’ The masses lit firecrackers to welcome Chairman Mao, such that smoke blurred their vision. Women shed tears of joy. When Chairman Mao’s image passed, the masses anxiously shouted: ‘Comrade! Show slowly! We haven’t gotten a clear look yet!’ So our comrade had to rewind the reel and replay the film to please the audience. When the audience saw how their representatives shook hands with Mao and received with welcome everywhere [in Beijing], they understood: their disunity with the Han before Liberation resulted entirely from the discord of Chiang Kai-shek’s bandits. They felt that Chairman Mao illuminated them like the sun.

This is one of many patronizing reports celebrating the cinematic enlightenment of backward and benighted audiences—highlighting the women, the elderly, and the disabled—and the cinematic governance of a formerly ungovernable, fragmented, and hostile populace, now rendered benign as singing and dancing ethnic minorities under Mao’s radiance. We might treat such reports less as reliable accounts of audience reaction than as literary performances by projectionists to testify to cinema’s ritual efficacy. Such texts also served as model scripts for other projectionists to ventriloquize the rural masses as communist converts through leader worship. The conceit of ‘Mao as sun’ permeated cultural production from the 1940s to the 1970s and finds a synthesis in the song ‘East is Red’ illustrated with posters and choreographies that feature the people as sunflowers (Fig 1). Besides symbolism, Mao’s cinematic image literally illuminated the dark night of the countryside off the power grid. This compels us to consider the mediation of the Mao cult and the cult value of mass media.

Fig 1. Choreography of the people as sunflowers surrounding the sun in the 1964 song-and-dance epic East is Red. Image from Morning Sun, Long Bow Group.

Studies of Mao’s personality cult, such as Daniel Leese’s Mao Cult: Rhetoric and Ritual in China’s Cultural Revolution, have focused on the CCP’s symbolic production, but little has been said of its dissemination and amplification through audio-visual media. Cinema not only mass reproduced Mao’s image and voice, but also congregated the masses for rituals of worship. Responding to projectionist reports, the Film Bureau issued directives to make additional copies of newsreels that included shots of Mao as early as 1956. Whereas cultural theorist Walter Benjamin famously polarised an artwork’s cult value and exhibition value, proposing that technological reproducibility leads to the withering of the aura, cinema enhanced Mao’s sacred aura and multiplied the altar of his personality cult: every screening of his moving image enabled a divine political figure to come down from his heavenly court onto the earth to meet with the people. In 1958, according to Film Projection magazine, the newsreel documentary Our Leaders Work with Us showed Mao digging at the Ming Tombs Reservoir and was met with an enthusiastic reception: ‘Chairman Mao took time out of his busy schedule to participate in labour—we must make more iron!’ Or ‘Even Chairman Mao is labouring—the idlers among us ought to be ashamed!’ As a quasi-labour model, Mao’s cinematic image aligned him with the peasants, workers, and soldiers, while the occasion of film screenings connected the masses with the leader, peripheries with the centre.

Even when Mao did not appear on film, villagers sent out gong-and-drum processions to welcome ‘Chairman Mao’s movie team’ or ‘honoured guests dispatched by Chairman Mao.’ Besides staging a vicarious encounter with the great leader, cinema became the culmination of technological wonders that inspired sublime feelings of awe for Mao and the Communist Party. Treating cinema as oracle and fulfilment of socialist modernity, projectionist reports often quoted elderly villagers: ‘Chairman Mao keeps his word: he said the countryside will have electrical light, telephones, and loudspeakers.’ A 1964 report considered the very arrival of a movie team in the countryside a form of political influence, since ‘the rural masses naturally associate cinema with the benevolence of the Party and Chairman Mao,’ regardless of what films they showed.

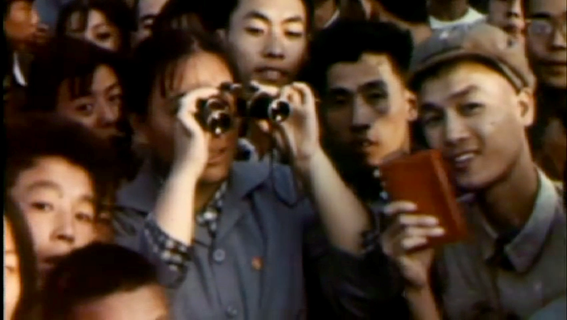

The cinematic cult of Mao reached its climax with newsreel documentaries of Mao’s 1966 meetings with millions of Red Guards on Tiananmen Square, films that came to be dubbed ‘red treasure films’ (hongbaopian 紅寶片) (Fig 2). Projectionists I interviewed in Zhejiang and Hubei recall having to screen these newsreels in every village on their circuit. Reinventing ritual processions for local cult deities, many village chiefs personally carried the film print with red ribbons and a Mao portrait from its last projection site. While landlords, rich peasants, counterrevolutionaries, bad elements and Rightists were banned from these screenings, according to a film history from Guangxi province, the revolutionary masses brought their ‘loyal, boundless, proletariat feelings.’ Indeed, the nationwide screenings recreated the mass rallies myriad times, and local organizations of reception parades in honour of Mao’s cinematic image adds a new dimension to our understanding of film reception.

Fig 2. Newsreel documentary of Mao’s first meeting with Red Guards on Tiananmen Square on August 18, 1966. Image from Morning Sun, Long Bow Group.

Retrospective accounts suggest highly varied reception of these Tiananmen rally films. Former Red Guards I interviewed in Shanghai recalled attending school-organised screenings of those films and clapping every time Mao appeared. Some were inspired by the first rally film to travel to Beijing to participate in a later rally. As workers in a Shanghai factory, my grandparents received free tickets but had no time to go, so they gave a movie ticket to my great-grandmother, an illiterate peasant woman who happened to be visiting Shanghai. After seeing the documentary, she commented on Mao’s nonchalant greeting of the young people’s enthusiasm, which my mother found ‘counterrevolutionary.’ Villager interviewees enjoyed those newsreels as vicarious travel to the capital and often puzzled over who was who on the Tiananmen rostrum. In rural Hubei, a female villager best remembered ‘Chairman Mao’s pretty wife’ Jiang Qing. In Ningxia, a villager recalled always seeing Lin Biao shoulder to shoulder next to Mao (Fig. 3):

He had on a bright green uniform, bright red insignia, and a big smile. When Mao clapped Lin would also clap, and we audiences clapped too. A villager once said Lin Biao was a ‘smiling tiger’ who looked like a traitor. Someone reported his comments, which got him executed as a counterrevolutionary. After Lin Biao really turned out to be a traitor, the villager was rehabilitated and his family received 10,000 yuan in compensation.

Fig. 3 An iconic and widely circulated photographic and film image of Mao with Lin Biao at the Tiananmen rostrum in 1966. Image from Morning Sun, Long Bow Group.

These stories of reception reveal audiences as cinematic guerrillas, but in different senses: while many young people were inspired to mobility as revolutionary pilgrims to meet Mao in person, others were less enchanted and harboured critical, even subversive thoughts. If the latter failed to keep these thoughts to themselves and got denounced, state-sponsored terror awaited them. While Lin Biao supported the Mao cult yet turned against the Chairman a few years later, the audiences learned from his costumes and expressions to play their parts as a devout congregation before Mao’s cinematic altar, regardless of the truth of their feelings. After all, the failure to perform a correct response had grave and violent consequences.

Note: This is a extract from the author’s book manuscript Cinematic Guerrillas: Maoist Propaganda as Spirit Mediumship, forthcoming with Columbia University Press.

Jie Li is John L. Loeb Associate Professor of the Humanities at Harvard. She is the author of Utopian Ruins: A Memorial Museum of the Mao Era and Shanghai Homes: Palimpsests of Private Life. Her forthcoming book, Cinematic Guerrillas: Maoist Propaganda as Spirit Mediumship, explores film exhibition and reception in socialist China.

- TV Drama Discourse on Stay-at-home Fathers in China: Super Dad & Super Kids - January 28, 2022

- Freud and China - January 20, 2022

- “Cultural China 2020″—A Different Take on China - January 7, 2022