Written by Piotr Strzalkowski

Through a careful choice of elements and sound composition, propaganda images often invite their audiences to experience a range of feelings and attitudes towards, e.g., individuals, groups, or ideas that they depict. This statement inherently applies to the sample of the anti-Japanese and anti-Communist caricatures, which are the subject of this blog post.

Scholars in cultural semiotics have emphasised the role of signs in texts of culture and their impact on the creation of collective consciousness through the emotions and values that they endorse (Semenenko 2012). Additionally, social psychologists identified relevant biases associated with emotions such as admiration, envy, contempt, and pity, which can impact one’s cognition and, in turn, behaviour (Cuddy et al. 2008). These notions correspond with the aims of visual propaganda (e.g., film, photography, or caricature) that seek to charge images with feelings.

While researching the Shanghai press issued during the Nanjing Decade (1927-1937), I have found multiple similarities between the visual conceptualisations of Japan and the USSR. These include analogous nature, attire, actions undertaken by Japan and the USSR towards China, and the emotional charge that the images propose towards both of them. It is a significant observation as several works on caricatures or political propaganda in China focused on Japan and overlooked examples that simultaneously included the USSR (Bi and Huang 2006; Gan 2008; Lent and Xu 2008), despite the said similarities between the two.

Before moving to the images, themselves, it is important to sketch out the major historical events that explain the appearance of the simultaneously anti-Japanese and anti-Soviet propaganda pieces in the early 20th century.

In the case of Japan, the relevant conflict points can be traced back to the First Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895 and the Treaty of Shimonoseki of 1895, as a result of which the Qing Empire lost Taiwan, the Liaodong Peninsula and suzerainty over Korea. Japan kept expanding its sphere of influence by utilising the political vacuum left after the fall of the Qing, leading to a period of unstable national governments during early Republican China. Tokyo also revealed the scale of its expansionist ambitions in the Twenty-One Demands that shocked the Chinese public and encouraged reoccurring boycotts of Japanese goods. The end of World War One brought further discord as the Treaty of Versailles stipulated the transfer of German colonial territories in Shandong to Japan. The decision sparked nationwide anti-imperialist outrage in the form of the May 4th Movement. Japan also financed warlord Zhang Zuolin, and when he became too independent, Tokyo invaded Manchuria in 1931, taking three Chinese provinces. After that, it targeted other regions hoping to subjugate them slowly. These actions were a prelude to the Second-Sino Japanese War in 1937.

Unlike Japan, the USSR was a new iteration of the Russian state that sought recognition on the international scene, which created both opportunities and challenges. Two Karahan Manifestoes, i.e., policy statements issued by the future Soviet ambassador to China, positioned Soviet Russia as a new friendly and generous state interested in resisting Western and Japanese imperialism present in China. The Bolsheviks publicly renounced the so-called Tsarist “unequal treaties,” but they also practised deceptive diplomacy that trapped China into perpetuating them. Their generous promises never materialised. The USSR did not return the Chinese Eastern Railway (sold to Japan in 1935) and kept Mongolia as its satellite state after the invasion in 1921. Moreover, the Soviet Union deceptively established a friendly relationship with the Beijing Government. However, it provided military and financial aid to its opponents, such as Feng Yuxiang’s Guominjun and the Guomindang allied with the Chinese Communist Party. It aimed to promote civil conflict to weaken relevant sides and use it as an opportunity to spread revolution, which failed due to Shanghai Massacre in 1927. The Guomindang-allied with anti-Communist warlord Zhang Zuolin who grew more assertive over the railway issue. Partly due to that, the USSR waged war in 1929 with China in Manchuria. Later on, the Soviets continued to meddle in Kumul Rebellion and seized a part of Xinjiang after an invasion in 1934. The Soviets also got involved in the Xi’an Incident of 1936. Despite again allying the Guomindang with Chinese Communists, the USSR got involved in another conflict in Xinjiang in 1937 and effectively took control over the whole province when China was at war with Japan.

The following conceptualisations help to visualise and examine actions undertaken by both Japan and the USSR during this time and highlight the perceived similarities between the two.

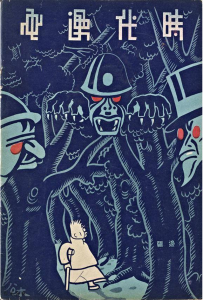

Fig. 1: Shidai Manhua, no. 14. 02.1935. Source: Modern Sketch (Shi Dai Man Hua) collection, M0099. Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University Libraries. Retrieved May 28, 2021, from https://archives.colgate.edu/repositories/2/resources/497

The first relevant example is Fig. 1 above, created by Mu Gong (木公) and printed on the back cover of the Shidai Manhua (時代漫畫), one of the most famous Chinese pictorial magazines of the 1930s. The caricature depicts a lonely Chinese man slowly travelling at night through a dangerous borderland (邊疆bianjiang), i.e., a forest full of monsters representing major military powers on the brutal international political scene. In contrast to them, the man is minuscule and needs to support himself with a cane as he has lost his leg. It, presumably, refers to Xinjiang partitioned by the USSR and Manchuria forcefully taken away by Japan. The narrow path and tunnel-like arrangement of the trees create a claustrophobic sensation suggesting that there is no place to escape, and that the additional danger may hide everywhere. All these signs symbolise his weakness and inability to resist threats.

The source of the man’s vulnerabilities seems not entirely related to his own mistakes, but circumstances presented above his head. In the treetops lurk three giant, red-eyed creatures with facial hair, namely the USSR, Japan, and the USA. Their big heads with red eyes, which symbolise danger and evil, stare at the man and create a sense of him being surrounded and outpowered. Only the Japanese monster shows his sharp claws and fangs as if he wants to attack again and devour China. Despite it, the two remaining creatures still seem to pose a threat.

The illustration invites the reader to feel pity towards the elderly man (China) and support him in a miserable situation. While at the same time, all three countries are powerful rivals, whose depiction provokes the reader to experience fear and the need for resistance. By regarding them through the lenses of the same prejudice, the propaganda roughly equated all three of them. However, in this period, the USA was not frequently equated with Japan or the USSR, which mainly appeared as imperialist menaces.

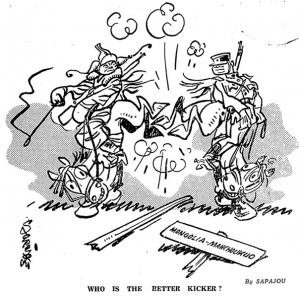

Fig. 2: The North-China Herald, 07.02.1933, 197. Source: The North China Herald Online. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. Retrieved May 28, 2021, from https://brill.com/view/db/nc

Another example, Fig. 2 above, focuses on emotions associated with stereotypes related to feelings of admiration and contempt. The image comes from the North-China Herald, a British colonial newspaper issued in Shanghai. Through the course of five scenes, it emphasises a significant decline in diplomatic modus operandi and the differences between the past and the current measures undertaken by Japan and the USSR.

The first four scenes glorify the mythologised past forms of diplomacy and show some positive responses to engagement with other parties. The first instance shows the Dutch flower diplomacy, which symbolises mild manners and style. These notions are further underlined by the usage of the ruff associated with upper classes, fashionable during Europe’s Early Modern period, and mutual exchange of courtesy. In other eras, proud poets are shown expressing their concerns while gentlemen in tuxedos and tall hats avoid dragging themselves and others through the mud, as symbolised by the white velvet gloves. Another instance refers to silent messages as diplomatic tools in conflicts in the American frontier between natives and settlers.

However, according to Sapajou, the Russian cartoonist for the North-China Herald, the Soviet-Japanese measures and multiple border conflicts in the 1930s were unacceptable and stood in striking contrast to the past forms of diplomatic conduct. The Japanese man and Stalin appear as dishonourable barbarians that throw rocks at each other and exchange prosaic slurs.

Overall, this image follows the paradigm of contrast. The first four scenes invite the reader to experience admiration and recognition towards those that exemplify actions and virtues worth emulating. Simultaneously, the image shows that when engaging in diplomacy, the USSR and Japan do not represent principles of calmness and esteem towards peers, unlike the four proceeding examples. As a result, the caricature encourages the reader to feel contempt and scorn towards the USSR and Japan.

This concise post demonstrates how anti-Communist and anti-Japanese propaganda invited its audiences to experience a particular set of emotions. These notions are relevant to other sources and demonstrate how images may invite certain emotions in response to broader geopolitical realities.

Scroll down for related images.

Piotr Strzalkowski is an early career researcher, who was recently awarded his AHRC-funded PhD in Chinese Studies from the University of Edinburgh. His dissertation is titled: “The Red Scare in China: Caricatures, Anti-Communist Propaganda, and the Foreign Press in the Interwar Shanghai, 1924-1937.” He is currently working on a paper related to this blog piece, the title of which is ‘Analogous Evils: Anti-Soviet and Anti-Japanese Propaganda Caricatures in the Shanghai Press, 1927-1937.’

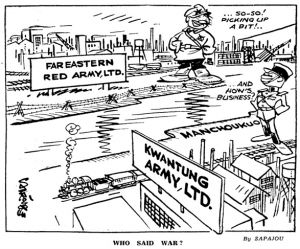

Fig. 3: The North-China Herald, 10.10.1934, 47. Source: The North China Herald Online. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. Retrieved May 28, 2021, from https://brill.com/view/db/nc

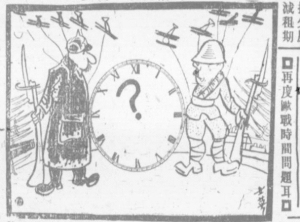

Fig. 4: Jingbao, no 2087, 07.02.1934, 4. By [Huang] Shiying. The issue of timing of another war in Europe (再度歐戰時間問題耳, zaidu ou zhan shijian wenti er). Source: Early Chinese Periodicals Online (ECPO), 1. Retrieved May 28, 2021, https://kjc-sv034.kjc.uni-heidelberg.de/ecpo/publications.php?magid=1

Fig. 5: Jingbao, no 2784, 07.02.1936, 4. By Shishi Yuemu. The background of a [current] rush towards equilibrium (衡突的背景, heng tu de beijing). Source: Early Chinese Periodicals Online (ECPO), 1. Retrieved May 28, 2021, https://kjc-sv034.kjc.uni-heidelberg.de/ecpo/publications.php?magid=1

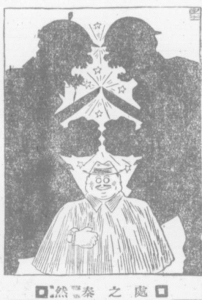

Fig. 6: Jingbao, no 2910, 14.06.1936, 4. By [Liao] Dongsheng. To handle the situation calmly (处之泰然, chuzhi tairan). Source: Early Chinese Periodicals Online (ECPO), 1. Retrieved May 28, 2021, https://kjc-sv034.kjc.uni-heidelberg.de/ecpo/publications.php?magid=1

Fig. 7: Jingbao, no 2384, 10.12.1934, 4. By [Huang] Shiying. To wait for an opportunity (窥伺, kuisi). Source: Early Chinese Periodicals Online (ECPO), 1. Retrieved May 28, 2021, https://kjc-sv034.kjc.uni-heidelberg.de/ecpo/publications.php?magid=1

Fig. 8: Jingbao, no 2837, 31.03.1936, 4. [Liao] Dongsheng. A sectional drawing of the equilibrium (衡突之剖面图, heng tu zhi poumian tu). Source: Early Chinese Periodicals Online (ECPO), 1. Retrieved May 28, 2021, https://kjc-sv034.kjc.uni-heidelberg.de/ecpo/publications.php?magid=1

Fig. 9: The North-China Herald, 19.02.1936, 293. Source: The North – China Herald and Supreme Court & Consular Gazette (1870-1941), ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chinese Newspapers Collection, 1766387, Retrieved May 28, 2021, from https://www.proquest.com/hnpchinesecollection/publication/1766387/citation/58DBCEE8E89545CFPQ

- TV Drama Discourse on Stay-at-home Fathers in China: Super Dad & Super Kids - January 28, 2022

- Freud and China - January 20, 2022

- “Cultural China 2020″—A Different Take on China - January 7, 2022