Written by Margaret Mih Tillman

Infants need constant care, and birthing parents bear the brunt of those demands. Many local Chinese traditions allowed postpartum women a full month of recovery and rest. Some of those prescriptions dovetail with current ideas about new-born care; so much so that some in the West are now following some of those traditional guidelines (Wisner 2018). Given the demands of professional working schedules, birth-rates have tended to decline in post-industrial societies. After three decades of family planning for the ‘One Child Policy,’ the Chinese state is now having difficulty convincing some women today to have children (Fincher 2021).

This trend not only reverses the People’s Republic of China’s family planning policy, but also its norms for revolutionary gendered labour. For Chinese revolutionaries, both women and children had been oppressed by the Confucian patriarch. As early as the 1920s, radicals proposed overturning the patriarchal norms in part by creating institutions that would relieve women of their family obligations for eldercare and childcare (Glosser 2008; Tillman 2018). By freeing women of domestic obligations, the revolutionary state would also mobilize the female workforce to contribute to the national good. As the writer Ding Ling wrote during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1927-1945), the Chinese Communist Party could not expect women to serve as party cadres when they were already doing a double shift at home (Ding 1990).

That logic became ingrained in workers’ campaigns after the People’s Republic of China was established in 1949. In the first two years of the PRC, the proliferation of day-care centres, which increased over a hundredfold, helped to increase the number of women workers threefold. Advocating for women workers, the Women’s Federation pointed to statistics about increases of worker productivity in factories with creches (Tillman 2018, 190). This logic found fruition in the Great Leap Forward, which ramped up childcare centres in the countryside, as well as collective kitchens, to alleviate domestic labour and integrate the community into a collective. The Great Leap Forward pushed millions of villagers to labour around the clock, with agricultural dayshifts and industrial nightshifts. Expected to provide endless surpluses, land and labour were overtaxed.

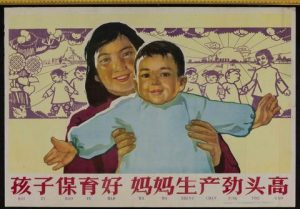

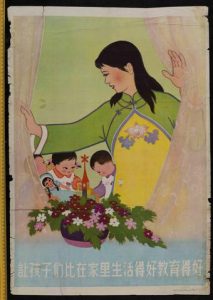

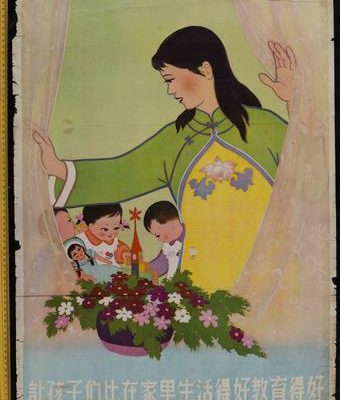

Who could care for children while also achieving ever higher levels of production? Mothers’ need for quality childcare is also the message behind these two attractive posters, both aimed primarily at women. (The absence of men reflects assumptions about the gendered nature of childcare.) In one poster, ‘If children are well looked after, Mum’s production drive is high,’ a mother holds up an infant who is facing outward, with his arms wide open (see Fig 1.). With early exposure to society, the confident and calm infant does not cling to his mother but embraces the outside world. He’s well cared-for at home; his classic smock indicates the mother’s attention to cleanliness. And he’s well cared-for in day-care. The background, hanging like a paper cut-out, displays the symbols of the prosperity and infrastructure of a socialist society; the Red Communist sun emits rays shining on a line of happy toddlers following their teacher. In another of these posters, a teacher opens a window onto a day-care so that viewers can see the happy scene inside, but even with her back slightly turned, the attentive teacher never allows the children to leave her sight (see Fig 1). The caption reads, ‘Let children live better and be better educated than at home.’ The children play with dolls and block toys as they construct their own small town—a miniature version of the ideal collective society that their parents hope to achieve. In day-cares, children embrace communitarian living and learn how to construct an ideal society.

Fig 1. If Children Are Well Looked After, Mum’s Production Drive is High (1960). Source: University of Westminster’s China Visual Arts Project.

Fig 2. Let the Children Live Better and Be Better Educated Than At Home (1959). Source: University of Westminster’s China Visual Arts Project.

Lest we misread these visual messages, Chinese fiction of the 1950s and 1960s abounds with model workers who are eager to leave domestic work to labour for the collective instead. The famous fictional heroine Li Shuangshuang leaves her daughter at home to contribute to the agricultural labour of the commune (Li 2010, 15-62). In Lin Jinlan’s short story 1960 ‘New Life,’ a captain is loath to depart from her thriving eggplants, even though the decision not to give birth in a hospital puts her life at risk (Hsia 2004, 390). In He Fei’s ‘A Big Family,’ a husband departs from his heavily pregnant wife to prepare, non-stop for two days, for provisioning a New Year’s Eve dinner at the commune. He’s left his wife in a leaky house in the midst of a raging snowstorm—not the ideal conditions for a traditional postpartum confinement. The husband’s negligence is redeemed by the equally altruistic acts of his neighbours, who have fixed the house and cared for his wife and new-born (Hsia 2004, 389-390). In a truly communitarian culture, it is right to sacrifice caring for one’s own children only and precisely because everyone prioritizes the collective. But what would have happened in a community without able-bodied adults?

Around the world, rural parents are leaving their children behind as they migrate elsewhere to work for higher pay. Most notably, when Southeast Asian women go abroad to care for families in the developed world, they entrust their own children to the care of others, thus creating a ‘global nanny chain (Parreñas 2015). In China, rural children are sometimes left with overworked grandparents, who till the soil alone; sometimes, children are even left alone. Institutionally, parents are disincentivized from bringing their children, who are only eligible for state benefits in education and medical care in the place of their home registrations. In 2013, the Women’s Federation estimated that ‘left-behind children’ had reached 61 million (Yang and Fuller 2018).

And the kids may not be alright. Child psychologists now emphasize the importance of parental ‘attachment’ in early childhood to future development. Chinese left-behind children often show signs of missing their parents as well as other mental distress (e.g., Jiang 2012; Shi et al., 2016). The multi-year, international Rural Education Action Project (REAP) suggested that after mothers leave the countryside, their children’s developmental, social, and emotional scores plummet (Normile 2017). Other surveys indicate that it is generally rural education that fails children (Zhou et al., 2015).

The conditions of China’s rural children have inspired a discourse on the ‘quality’ of its population. This rhetoric has a Neo-Eugenicist ring that further privileges urban, middle-class children (Greenhalgh 2010; Fincher 2021). Nevertheless, in the context of genuine concern about rural education and medical care, this discourse also acknowledges that the nation cannot endlessly harvest the labour of parents without nurturing the next generation of metaphorical ‘crops.’

The Chinese Communist Party has long recognized that mothers need to be assured that their kids are alright when they return to work. But assurances are not enough. Children’s actual wellbeing has just as much an impact on the nation as their parents’ labour contributions.

This is a problem without easy solutions. Extended Covid-19 quarantine has driven even some American women—even white-collar workers who have the luxury of working from home—out of the workforce as day-care centres shut down and schools meet virtually (Hsu, 2021). The demand for childcare has also put pressure on the US’s ‘nanny chain,’ as Black, Asian, and Latina women, who have traditionally dominated the childcare service sector, struggle even harder to find care for their own children (Mueller, 2020). While productivity was once measured in terms of output alone, we may now have to factor the wellbeing of children (and parental labour) into a new calculus of the social good.

Margaret Mih Tillman is Associate Professor of History and Director of Asian Studies at Purdue University. She is the author of Raising China’s Revolutionaries. She is also a proud first-time mother to a happy and healthy infant son.

Image credit: Let the Children Live Better and Be Better Educated Than At Home (1959). Source: University of Westminster’s China Visual Arts Project.

- TV Drama Discourse on Stay-at-home Fathers in China: Super Dad & Super Kids - January 28, 2022

- Freud and China - January 20, 2022

- “Cultural China 2020″—A Different Take on China - January 7, 2022

[…] second piece, written by Margaret Mih Tillman, takes a look at collective childcare in the early years of the PRC, with a particular focus on […]