Written by Sabina Cioboata

Following decades of reform and rapid growth in China, urban regeneration has been one of the most transformative phenomena for cities and their dwellers. Under the umbrella of cultural or heritage-led regeneration, state and market- dominated projects have been scrutinised for their growth-oriented agendas and socio-cultural costs. Nevertheless, a closer look may reveal a more complex picture as attempts are being made to address some of the shortcomings of past approaches.

Driven by influxes of foreign investment after China’s opening up, coastal cities such as Shanghai actively embraced various strategies to become national multifunctional centres and globally competitive mega-cities. During the 1990s and early 2000s, this materialised in a series of large-scale urban regeneration projects. Within this process, a selectively remembered and incorporated past has served a political and social agenda for branding, intense city competition, and the creation of global metropolises.

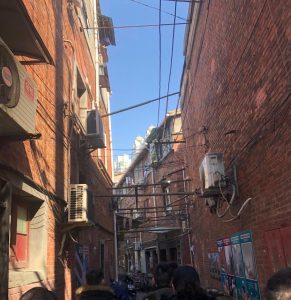

If visitors wander through Shanghai in search of fragments of urban heritage, chances are that they will be swiftly directed towards areas such as Huangpu District’s affluent Xintiandi or its neighbour, Tianzifang. Both areas are located in the geographic centre of Shanghai and represent preserved historic Shanghainese lanes (lilong) lined with shikumen architecture: a distinctive type of Shanghainese residential form which developed between the late 19th Century and the 1920s, when the city experienced its first wave of globally connected economic growth and socio-cultural transition. Combining Western townhouse architectural style and Chinese courtyard house elements, they constituted the largest and most concentrated segment of Shanghai’s residential landscape and continue to represent a symbol of the city’s unique history and identity.

In the 1990s, Shanghai underwent a large-scale urban re-development under a plan which stipulated that by the year 2000, the city would demolish and rebuild 365 hectares of “dilapidated housing” stock. Within this context, Xintiandi was part of the 1991-2000 ‘Taipingqiao Redevelopment Project’, wherein 52 hectares of housing were to be torn down and redeveloped into a high-end residential and commercial district. 640,000 households were relocated and offered monetary compensation negotiated on a case-by-case basis, albeit as part of a coercive process with minimal choice for residents. The project was carried out by a private Hong Kong developer in partnership with the local District Government, under the supervision of the Shanghai Municipal Government – a type of regime-like growth coalition which dominated urban renewal at the time. At the heart of the re-development area, two blocks of shikumen were preserved and adaptively reused as a luxury retail and entertainment zone in the style of Western ‘lifestyle centres’. It was emblematically named Xintiandi (New Heaven and Earth, or figuratively, New World). Targeted at shaping the imaginaries of a rising middle class and attracting their consumer power, the project staged an iconic space where re-imagined memories of a romanticised, ‘cosmopolitan’ past met commercialisation and current-forms of globalisation– all the while veiling a multifaceted process of spatial differentiation and rising inequality.

Shortly after, however, the power structures and mechanisms involved in heritage-led urban regeneration started to shift. The regeneration processes and directions set by the developer-government coalitions were increasingly being challenged by grassroots movements, including professional elites and local communities. This phenomenon was clearly evidenced in Tianzifang, an urban renewal case which took a very different direction to that of Xintiandi, despite their geographic proximity. Also located in Taipingqiao, Tianzifang is a lilong area bordered by a road containing six vacant factories which, after being decommissioned in the 1990s, were lent out and transformed into art studios. Progressively, communities of artists also started renting out shikumen housing for residential and workshop purposes, prompting the government to designate Tianzifang as a ‘concentrated creative industry’ area in 2005. A gradual process of gentrification commenced as non-residential use was gradually extended, similarly capitalising on the commercial potential of the site’s cultural and heritage elements. This also catalysed a process of on-site housing upgrade which improved living conditions for those who preferred to stay, primarily financed and guided by local resident organisations. It is in this sense that the Tianzifang renewal project was substantially different from its counterpart, Xintiandi. Despite resulting in a similarly curated space of cultural consumption, the resident community of the former had choice and autonomy over not only their shared past, but also their present and future.

In the last decade, significant policy and practice reforms have aimed at further addressing the imbalances caused by previous urban re-development models, while maintaining stability and working towards recent political ambitions of “building a harmonious society”. In 2015, the Shanghai Municipal Government launched a set of policy measures calling, amongst others, for public participation and people-centred, innovative approaches in neighbourhood revitalisation. Towards this goal, sub-district governments and neighbourhood committees have launched in recent years a series of ‘micro-scale urban regeneration’ (weigengxin) projects, targeting urban historical blocks with urgent need for renewal. Such projects are characterised by preservation and incremental upgrade as opposed to demolition and relocation – a less invasive approach applying place-based solutions to local problems. They also aim to challenge previous top-down governance models by piloting alternative, collaborative processes for built environment transformation.

Shanghai’s Chengxingli and Chunyangli are some of the first pilot projects experimenting with such approaches since 2017. Both are inhabited lilong areas suffering from poor quality of life following processes of expropriation after 1949, when the state confiscated housing stock from individual property owners and redistributed it to accommodate multiple households. The projects’ strategies included preserving the morphology and scale of the lilong area, improving public space, and renovating/rebuilding the historic façades, while re-designing the interiors in order to increase living space and add previously inexistent facilities such as private kitchens and bathrooms. According to recent reports, all interventions were carried out following extensive rounds of public consultation and addressing individual household needs, in an attempt to preserve the neighbourhoods’ social structure.

Such projects are intriguing from several points of view. Firstly, they challenge concepts of authenticity which have long produced a split between heritage conservation and urban development. In contrast with more conservative heritage safeguarding approaches that have often led to residential displacement and ‘museification’ in the name of conservation, this project understands authenticity as continuity of use, employing design innovation to ensure the preservation of the social fabric. This also confronts long-engrained imaginaries of modernity, showcasing to Shanghainese urbanites alternative ways of ‘modern’ living, beyond the high-rise apartment. Meanwhile, those with different aspirations have the choice of renting out their properties to white-collar workers: a strategy envisaged to start an organic process of demographic regeneration and to ensure the neighbourhoods’ future maintenance and revitalisation. In terms of governance, the projects were aimed at stimulating grassroots governance and community building, mediated by independent planners and NGOs. This could be interpreted as an interesting dichotomous agenda in China: while current participatory urban planning and design approaches are more just and sustainable, community building processes can also be used as mechanisms for ensuring social stability and control in the long term.

As in many parts of the world, culture and heritage-led urban regeneration in China have blended globally circulated simulacra with efforts to build national and city identity. In the future, as Chinese city mechanisms continue to reform, it will be important to keep scrutinising their ambitions of fostering sustainability and leaving no one behind.

Sabina Cioboata is a PhD researcher at University of Westminster’s School of Architecture and Cities. Her current, inter-disciplinary research explores urban regeneration and transitions to a wellbeing-oriented agenda in China. Her journey in China began during a three-year collaboration with WHITR-AP Shanghai: an Asia-Pacific research and training institute affiliated with UNESCO. She has previously been involved in short-term research projects in Romania, Bhutan and the Philippines. Image credit: author.

- TV Drama Discourse on Stay-at-home Fathers in China: Super Dad & Super Kids - January 28, 2022

- Freud and China - January 20, 2022

- “Cultural China 2020″—A Different Take on China - January 7, 2022

[…] third piece, written by Sabina Cioboata, reflects on heritage-led urban regeneration. She examines the transition from large-scale, […]