Written by Sophie Xiaofei Guo

The Taiwanese artist Pei-Ying Lin started her thought experiments about viruses as early as 2011. From Smallpox Syndrome (2012-2015), Tame is to Tame (2016) to her latest work Virophilia (2018-ongoing), Lin imagines an alternative future where pandemics have become common occurrences. Instead of using the twentieth-century metaphor of war for describing the relationship between humans and infectious agents, which still pervades the realm of science and mainstream media today, Lin’s work embraces an ecological perspective and a positive attitude to our relationship with viruses.

Conceived two years before the COVID-19 outbreak, Virophilia is a prescient project imagining new ways of viral encounters in the future. It registers a radical rethinking of the ontology and epistemology concerning the body and human-microbe relationship via a set of culinary designs that engage viral agents as active ingredients. Borrowing methods from speculative design, Lin has staged numerous ‘virus dinner performances’ with invited participants from different cultural backgrounds, in order to probe the cultural logic behind their diverse attitudes towards virus and disease.

Figure 1. Pei-Ying Lin, ‘Virophilia Dinner Performance Quarantine Edition’, 20 June 2020, C-LAB, Taipei. © C-Lab

On the 20th of June last year, Taiwan Contemporary Culture Lab (C-LAB) staged an online virus dinner performance under a ‘quarantine condition’. Meals that were specially designed to engage viruses as ingredients were delivered to around 15 participants for them to consume from their homes in Taipei, while Lin remotely provided the instructions from The Netherlands to the participants on how to experience their virus food.

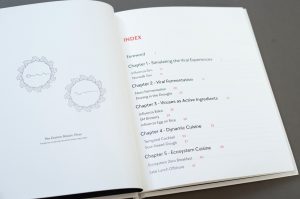

Figure 2. Pei-Ying Lin, ‘Cookbook for the Virophilia-ists in the 22nd Century’ Table of Contents, 2018. © Pei-Ying Lin

The project consists of a future cookbook (known as ‘Cookbook for the Virophilia-ists in the 22nd Century’), an installation of scrolls listing the names of all known virus species to date (published by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses), a video that shows the process of a Taiwanese female performer consuming her virus dinner, and a live dinner performance that involves participants from the public experiencing the viruses in their food.

Though invisible to the human eye, microbes surrounding and inside the human body, co-existing and co-evolving with us, as the artist believes, are far greater in quantity than we generally recognise. Virophilia therefore, is intended to facilitate the perception of viral existence and generate proactive (instead of passive) relationships with viruses, especially with the infectious ones, by means of culinary design, and via the intimacy of dining encounter.

In the performance, Lin created a scenario of a cross-temporal collaboration between what she called ‘the government of earthlings’ from the future of 2210 and the C-LAB from 2020. Imagining herself as a representative of this fictional government, the artist wanted to reach back in time in order to save the ‘vulnerable group of viruses’ from being wiped out from the planet. For this government, the hierarchy and binary relationships between humans and non-human creatures are altered. As the smallest of all the microbes, viruses are neither fully dead nor fully alive but exist on a spectrum of liveliness. They are parasites that cannot replicate without the host cell of other living beings. Nevertheless, the ‘government of earthlings’ treats them on an equal footing with other living beings.

The virus meal consisted of three courses. The first course called the ‘Unique Mayonnaise’ contained influenza viruses that had been injected into the raw egg yolks so that they would replicate. As the participants consumed the mayonnaise with the egg yolks, they felt a hot and slightly tingly sensation in their throat, marking the moment when the virus particles began penetrating the host cells and triggering responses from the body’s immune system. The artist imagines that by 2042, dishes like the ‘Unique Mayonnaise’ could protect the eater from the seasonal flu. Via the medium of food, the participants would gain a sensory experience of viruses entering the body.

The second and third courses both involved the change of texture, flavour and morphologies of food as its ingredients had undergone the process of what the artist called ‘viral fermentation’. Lin envisions that by 2037 this can be widely achieved through a precise control on virus strains so that the degree and timing of viral infection of the ingredients can be accurately managed.

More radically, the artist imagines a future where human beings themselves take part in what she calls the ‘ecosystem cuisine’ as a source of nutrition for other earthlings to enjoy. Humans participate in the ecosystem of recycling, circulating and exchanging energy and nutrition with other living beings. In this system, humans become the fodder of beings, subject to the use of others (Steel 2018, 160). Virophilia is designed in a way that resonates with philosopher Jane Bennett’s ecological conception of the body, which argues that ‘it is not enough to say that we are “embodied”‘. We are, rather, an array of bodies, many different kinds of them in a nested set of microbiomes’ (Bennett 2010, 113).

Lin’s conscious making of a microbial body and the imagining of a viral future takes its epistemological root in the moment of what science historians have called the ‘microbial turn’ in biological science since the turn of the 21st century. At the beginning of the 20th century, the microbe was perceived in adversarial terms across science, medicine and culture as an enemy to be eliminated from the human body; in the 21st century, the relationship between microbes and disease has been increasingly reconfigured from the ‘microbe’s eye view’ and in ecological terms (Sangodeyi 2014). Microbiologists have developed the theory that infection is a result of ecological disturbance as opposed to an attack by a pathogenic agent (Lederberg 2000).

In the face of COVID predicament, however, Lin’s imagining of a biofuture for positive relationships between humans and viruses may sound overly utopian. But this intentional rendering of simplicity, fictionality, and provocation is a strategy that Lin deploys from the discipline of speculative design. This method intends to transform the participants into ‘citizen-consumers’ and encourage them to critically engage with the ‘fictional products, services, and systems from alternative futures’ (Dunne and Raby 2013, 49).

The artist’s recent success in staging this performance in Taiwan right in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic is worth reflecting on in its own right. The participants’ receptive attitude towards the idea of the human body as microbial and their demonstration of trust in consuming the virus meal need to be understood in relation to the institutional, cultural and socio-political changes that have occurred in post-SARS Taiwan.

After the painful lesson of the 2003 SARS epidemic, the government has fundamentally improved its epidemic prevention system to ensure that it is well-prepared for the possibility of a coronavirus-related pandemic (O’Flaherty 2020). The aftermath of the SARS crisis also saw the development of government-funded biomedical research projects. Taiwan in 2005 launched a national project to develop the country as ‘Biomedtech Island—an Asian hub for biomedical technology’ (Liu and Gardner 2012).

In the cultural sphere, the government has sponsored art projects and institutions that take an interdisciplinary approach and engage ideas of innovation with Asian and Taiwanese cultural specificities. The C-LAB is such a case in point. It was founded by the Ministry of Culture in 2018. Its programmes have so far shown a strong focus on digital art and technologically informed, experimental art practices and debates. Biomedically engaged art practices started to emerge in Taiwan in 2009 and proliferated from 2017 following an increase in the number of biomedical research laboratories as well as more opportunities for international exchange (Chiu 2020).

Through a collective effort to stop the spread of COVID-19 from as early as mid-April last year without a lockdown and managing to avoid domestic infection for 200 days, the trust demonstrated in the process of the dinner performance perhaps mirrored the institutional trust, civic solidarity and the qualities of what Byung-Chul Han called ‘civility and responsibility towards others’ within this Asian civil society during the pandemic (Han 2020). This was the case until very recently, when Taiwan experienced a sudden surge in cases due to complacency and vaccine shortfalls (Tan 2021). Medical authorities from Taiwan have advocated for a shift in mindset in the face of the coronavirus, suggesting that humans might have to try co-existing peacefully with viruses (Wang 2020). The ecological approach to viruses as a major epistemological shift suggested in Virophilia might not be as utopian and farfetched as it seems.

Sophie Xiaofei Guo is a PhD candidate at The Courtauld Institute of Art. Her thesis examines how biomedicine has transformed image-making in Sinophone cultures from the late 1980s to the present day. Her publications include ‘Doubting Sex: Examining the Biomedical Gaze in Lu Yang’s UterusMan’ (2019), ‘Gender in Chinese Contemporary Art’ (2018), and ‘“We Will Infiltrate Your Bloodline”: Biohacking Gender, Trans Aesthetics and the Making of Queer Kinship in the Work of Jes Fan’ (forthcoming book chapter).

- TV Drama Discourse on Stay-at-home Fathers in China: Super Dad & Super Kids - January 28, 2022

- Freud and China - January 20, 2022

- “Cultural China 2020″—A Different Take on China - January 7, 2022

[…] the third piece, Sophie Xiaofei Guo takes a look at artistic practices about pandemics in Taiwan. Focusing on the work of Pei-Ying […]