By Wen Hua

SoYoung, one of the biggest Chinese cosmetic surgery mobile apps, released a report in 2017 stating that the Chinese cosmetic surgery market was developing at six times faster than the global average in terms of the number of people undergoing non-surgical and surgical procedures. It also noted that Chinese consumers accounted for around 41% of the global total cosmetic surgeries, among which about 10 percent of consumers were men (Sina, 2017).

Compared with their female counterparts, beautification practices for men constitute new territory. To participate in the improvement of one’s appearance through daily grooming, let alone through surgery, men need to overcome their entrenched perception of beautification practice as women’s domain. Who are these men and what procedures do they opt for? What does the new trend of male beauty in China look like, and how do beautification practices affect constructions of masculinity?

It has been widely reported (China.org.cn, 2003; Wang and Cai, 2016) that entertainers, young white-collar workers, successful career men in their 40 and 50s, and colleague students are the main customers of male cosmetic surgery in China. Male entertainers such as models, actors and TV hosts are generally more concerned about appearance, in all its aspects, because appearance is particularly important for their career development. Although male and female public figures seldom admit they have undergone cosmetic surgeries, Hu Ge, one of most influential Chinese male celebrities appearing on the covers of most fashion magazines, admitted that he underwent a number of procedures to restore his looks after he had a serious car accident in 2006.

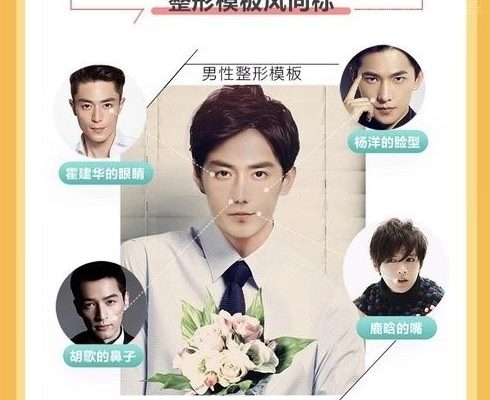

Young white-collar workers normally opt for small operations rather than going under “the big knife”; typical procedures include nose jobs (rhinoplasty), jawline recontouring, and “double-eyelid surgery”. For successful middle-aged men, they are more concerned with aging, the signs of which they combat by having eye bags reduced, sagging cheeks, jowls and necks restored, hair implanted, and excess fat removed by liposuction. Less invasive procedures such as injections of Botox or hyaluronic acid, which reduce wrinkles and help the skin look younger, are also popular. Young students who ask their parents to pay for their surgery sometimes go to cosmetic surgery clinics and hospitals armed with pictures of movie stars and pop stars. Genmei (2016), another influential cosmetic surgery app, reported that the most desirable facial features of China’s male cosmetic surgery trend were the eyes of including eyes of Huo Jianhua, nose of Hu Ge, face of Yang Yang, and mouth of Lu Han. Popular procedures for this group included “double eyelid surgery” (to make their eyes appear larger), together with operations to sculpt their noses or shave their jawbones to produce a softer face.

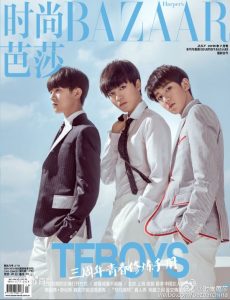

TF Boys on the cover of Bazaar, July 2016. Image source.

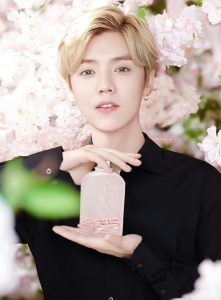

The increasing popularity of male cosmetic surgery shows the rise of aesthetically conscious men in China. In the past decades, the media, soap operas, and lifestyle magazines have been saturated with messages about men discovering their “feminine” sense of beauty. A new type of male beauty idol, “flower boys”, or in a new catchword, xiaoxianrou – literally, “little fresh meat”, – has become extremely popular as a label of a new type of Chinese male icon, who are known for their flawless, boyish appearance, exemplified by the cute-faced TF Boys, one of China’s most popular teenage boy bands. Although there are different ranking charts for the most popular xiaoxianrou, celebrities such as TF Boys, Lu Han, Wu Yifan, and Yang Yang appear in most of charts.” These male idols are shaping new images of male beauty, which is in contrast to the macho stereotype tough guy image which dominated the Mao era. The rise of “flower boys” and xiaoxianrou is not limited to China. Something very similar has also taken place in other Asian countries, especially Japan and South Korea (Holliday and Elfving-Hwang 2012; Jung 2011; Miller 2003). The rise of “flower boys” and men’s growing interest in their appearance challenges conventional macho masculinity and presents an alternative soft masculinity, or “metrosexual” in Simpson’s term (1994).

Lu Han as a spokesperson for a cosmetic product. Image source.

The term “masculinity” in Chinese today, yanggangzhi qi, implies “macho”. However, scholars (Louie, 2002; Song, 2004) have argued that the configurations of Western hegemonic macho masculinity are not applicable to masculinity in China. In Chinese history, sometimes soft wen masculinity was superior to macho wu masculinity because it was the literary skills and cultural attainments conceptualized as wen masculinity that was more closely associated with social status than wu macho masculinity. Of course, there is never just one kind of masculinity and masculinities change over time. As Connell and Messerschmidt (2005: 836) argue, masculinities are “configurations of practices that are accomplished in social interaction and, therefore, can differ according to the gender relations in a particular social setting”.

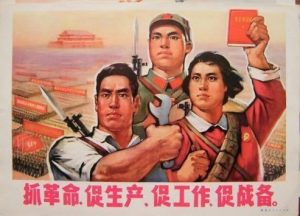

Under the revolutionary ideology of the Maoist China form the 1950s to the later 1970s, the traditional predominance of wen masculinity over wu masculinity was overturned when intellectuals were labelled as “bourgeois rightists” and workers, peasants, and soldiers (gong, nong, bing) as the proletariat central to the power of the state. The hegemonic macho masculinity was exemplified by strong and muscular “iron girls” (tie guniang) who were supposed to look and act like men.

Propaganda of workers, peasants, and soldiers (gong, nong, bing) in the Maoist China. Image source.

Wen masculinity made a come back following China’s reform and opening-up in the 1980s. With consumerism becoming increasingly important during this time, wen masculinity came to embody not only scholarly attainment, but also an ability to consume. It also became associated with metrosexual traits, as vividly exemplified by the rise of aesthetically conscious “flower boys” or “little fresh meat” and beauty products advertised by those influential androgynous male idols. As part of this consumer culture, an attractive and groomed male body has come to represent a new form of sophisticated identity and consumerist masculinity.

The rise and popularity of “little fresh meat” challenges representations of masculinity in contemporary China, and has received a strong pushback from powerful state media. The state news agency Xinhua published an editorial denouncing “sissy pants” (niangpao) or those who are “slender and weak,” warning of the adverse impact of this “sick” culture on teenagers (Xing 2016). The editorial stressed that “what a society’s pop culture should embrace, reject and spread is really critical to the future of the country.” While some fear the popularity of effeminate male idols may threaten the country’s future (see Teixeira 2018), others believe in an open and diverse society. Aesthetics can be varied and there is plenty of room for diversity.

Wen Hua received her Ph.D. in Anthropology from the Chinese University of Hong Kong in 2010. She was a visiting fellow of Gender Research Programme at Utrecht University in 2007. Wen has published several papers on gender issues in English and Chinese journals. She is the author of Buying Beauty: Cosmetic Surgery in China (Hong Kong University Press, 2013). Image credit: 36Kr.

- TV Drama Discourse on Stay-at-home Fathers in China: Super Dad & Super Kids - January 28, 2022

- Freud and China - January 20, 2022

- “Cultural China 2020″—A Different Take on China - January 7, 2022

[…] four, written by Wen Hua, examines beauty practices among men in China today. Wen describes how and why cosmetic surgery and […]

Cosmetic surgery in China is highly developed! Magnificent examples of successful plastic surgery are amazing!