Written by Amy Jane Barnes

To China’s communist leader Chairman Mao Zedong (1893-1976), art and design was integral to revolution. Following Lenin’s lead, he argued that there was ‘no such thing as art for art’s sake’ – all art was political and should play an integral role in founding, developing and maintaining the revolutionary spirit of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). And, when it came to his vision for the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), the arts and culture played a crucial role. Through posters and performances, revolutionary ideals could be directly disseminated to ‘the masses’. Several styles of art emerged, including ‘revolutionary romanticism’, a mash-up between traditional brush and ink painting and Soviet social realism. This will be familiar to anyone who has seen a propaganda poster from this era. But the genre I want to focus on in this blogpost, is so-called peasant painting and an exhibition of this type of work that toured Britain from 1976 to 1977. This exhibition was significant because it was one of the first opportunities that many British people had to see revolutionary art from China. And it also represented a thaw in the Sino-British political and cultural relationship, straddling the last years of Mao Zedong’s life and the appearance of a new style of communism under Premier Deng Xiaoping, which shaped the China we know today.

Art and Design under Mao Zedong

Revolutionary romanticism dominated art and design in China, particularly during the early years of the Cultural Revolution. This genre of work typically depicts heroic workers, peasants and soldiers in dynamic poses that visually evidence their revolutionary zeal. To Western eyes, some of these works may appear naïve, but they typically feature layers of iconographical meanings that could be ‘read’ by those familiar with this visual language. To give just two examples, the colour red represents revolutionary fervour and sunflowers turning towards the sun are a metaphor for Mao’s leadership of the masses. Often disseminated as cheap, mass-produced posters (some of which made their way to the West through periodicals, magazines and left-wing bookshops), these images were accompanied by bombastic slogans extolling revolutionary behaviour or beliefs. These works were often published anonymously or authorship was assigned to a collective of cultural workers, particularly during the first half the Cultural Revolution. Art was not meant to be a reflection of its maker’s talent. It was purely functional and stringently controlled. Although some ‘peasant painting’ followed this model, most other examples diverge from this ‘norm’. There are solid, ideological reasons for this that we can understand better by exploring the development of peasant painting as a genre.

Peasant Painting

The most famous peasant painters came from the Huxian model art commune in Shaanxi province. The ideological premise was that these artists were untrained amateurs and they were singled out by the cultural authorities because their innate talents contradicted the view, supposedly held by Marshal Lin Biao (1907-1971) (who by this point in time had spectacularly and posthumously fallen from grace by heading up an ill-feted military coup), that not everyone could be an artist. Although it is now accepted that peasant painters were in fact provided with copy books and professional training, the story prevailed. These paintings were intended to be viewed as spontaneous expressions of the revolutionary spirit of the masses and evidence for the success of Maoism in the countryside. The Chinese cultural authorities were keen to promote peasant painting internationally through publications and exhibitions, not least because it provided ‘evidence’ for the success of the Chinese revolution. But peasant painting also became a pawn in internal wrangling for power within the Chinese Communist Party, as Chairman Mao grew older and became unwell.

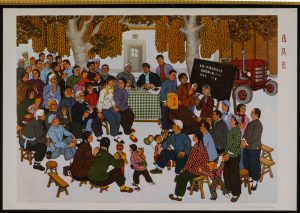

Peasant painters captured idealised scenes from commune life. Choosing a Team Leader, artist unknown (c. early 1970s), University of Westminster Archive

In the early 1970s, the relationship between China and the Western powers began to thaw. In 1971, the PRC was given a seat at the United Nations and, in 1972, US President Richard Nixon made a high-profile visit to the country. Because of Mao’s increasing frailty, Zhou Enlai (1898-1976) played a very visible role in the Nixon visit. Jiang Qing (1914-1991), Mao’s fourth wife and China’s culture supremo, was sidelined. Her hardline principles were challenged by Zhou’s more moderate views, especially in the cultural sphere. He oversaw a relative relaxation of controls on artistic expression, promoting pre-revolutionary style guohua (brush and ink painting) and apparently neutral themes, such as birds and flowers. Jiang, in contrast, remained defiantly committed to Maoist art ideologies. As such she was a fervent supporter of peasant painting.

Peasant Paintings from Hu County

Around the time that Nixon visited China, relations between Britain and China also improved and, as a result, plans were put in place for cultural exchanges that acknowledged developing diplomatic, economic and trade relationships. One such venture, the exhibition The Genius of China, saw a number of recent archaeological finds exhibited in London at the Royal Academy in 1973-4. But the exhibition presented little of ‘New China’, instead focusing on major archaeological discoveries, including Qin Shihuangdi’s tomb (aka ‘The First Emperor’), guarded by his famous Terracotta Warriors. In 1976, the Chinese authorities offered a selection of peasant paintings, then on tour in Sweden. These were accepted by the Arts Council on the proviso that after display in London (at the Warehouse Gallery, Covent Garden and the Hayward Gallery thereafter), the exhibition would be available to tour the UK into the following year. It was eventually shown at a number of venues, including University College, Cardiff; Nottingham Castle Museum; Birmingham Central Library; and the Scottish Arts Council Gallery in Edinburgh.

The exhibition comprised 80 paintings, the majority of which were original works painted in 1973 by around 60 individuals. Among those selected for display was Dong Zhengyi’s The Commune’s Fishpond, which was one the then best-known peasant paintings in the West. The catalogue, Peasant Paintings of Hu County, Shensi Province, China, Arts Council of Great Britain (1976), was written by Guy Brett, a journalist and lecturer who had championed revolutionary art from China and was sympathetic to Maoism. It is perhaps not surprising, therefore, that the interpretation of the paintings offered by the catalogue echoes the official Chinese line. In hindsight, Brett presents a naïve vision of the revolution and the legacy of its effects on the countryside and on artistic production. But it is important to remember that at this time, access to news, art and culture from Mao’s China was limited. And those Westerners whom, like Brett, had travelled to China during the Cultural Revolution, experienced a stage-managed, deftly controlled version of everyday life in China.

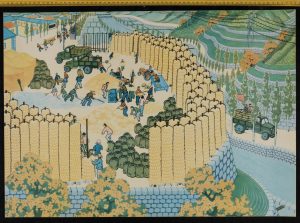

Bountiful harvests were a key theme of Huxian peasant paintings. Maize Harvest on River Bank, artist unknown (c. early 1970s), University of Westminster Archive

The exhibition, in its various venues, was generally well-received. The Arts Council collected and recorded a range of responses from newspaper reviews to comments books. Review articles suggest that the paintings were largely accepted as accurate representations of life in China. The transcript of an edition of BBC Radio 4’s Kaleidoscope programme, broadcast in November 1976, reveals that the presenters were preoccupied with the notion of ‘communality’ as expressed by the artists in their work. One wonders if this was more reflective of the mid-1970s cultural zeitgeist in Britain – self-sufficiency and alternative ways of living – than a genuine interest in the everyday life of Chinese peasants. Some members of the public were less convinced by the paintings. One visitor remarked, ‘ … do the Chinese always smile?’ Others expressed concern that the works were ‘too political’. One wag suggested that the peasant painters of China could learn a thing or two from the pupils of a local high school in terms of artistic talent. But others had more positive reactions to the works on show and clearly valued the opportunity to make contact with ‘a culture so different from our own’: ‘No matter what criticism of the modern Chinese paintings can be made they are undoubtedly an indication of the devotion of the Chinese to a new way of life and more illustrative of its results than much newspaper information and many books’. And this, after all, lay at the heart of the exhibition’s conception and execution. The tone of the exhibition and the openness in which it was (mostly) received, echoed the growing friendship between Britain and China.

This has been a brief overview of the exhibition, Peasant Paintings from Hu County. If you would like to read more about the political and cultural context in which the exhibition was developed, interpreted and understood, please refer to Chapter 5 of my book, Museum Representations of Maoist China (Ashgate/Routledge, 2014), from which this blogpost was adapted. Information about the sources consulted, including archival material, can also be found in my book.

Amy Jane Barnes is a Staff Tutor in Art History at The Open University. She has previously worked in research and teaching roles at several higher education institutions, including the University of Leicester, University of Warwick, and Loughborough University. She was awarded a PhD in Museum Studies from the University of Leicester in 2010. Her monograph, Museum Representations of Maoist China (Ashgate/Routledge) was published in 2014. She is co-editor of several volumes, including A Museum Studies Approach to Heritage (Routledge, 2018). Image credit: Dong Zhengyi’s The Commune’s Fishpond (1973), one of the best-known peasant paintings in the West, from the University of Westminster Archive.

- TV Drama Discourse on Stay-at-home Fathers in China: Super Dad & Super Kids - January 28, 2022

- Freud and China - January 20, 2022

- “Cultural China 2020″—A Different Take on China - January 7, 2022

[…] the third piece, Amy-Jane Barnes examines a ‘peasant painting’ exhibition that toured Britain from 1976 to 1977. Barnes […]