Written by Jon Howlett

Most historians of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) are avid collectors of curios: items that capture the spirit of certain historical moments in modern China’s ever-changing political climate. In this blog, I use a recipe book for train staff published in 1978 by the passenger department of the Guangzhou Railway Bureau, titled Menus and Resources for Western Cuisine, as an entryway to explore the history of the short-lived Hua Guofeng era (1976-1978) on its own terms.

Fig 1. Menus and Resources for Western Cuisine (Part One) (note: the book has a different title on the outer cover).

Politics pervaded every public and private space in late 1970s China. Between 1966 and 1976, the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution had plunged the country into tumult. Militant Red Guards had competed to show their dedication to Chairman Mao Zedong through the violent persecution of ‘class enemies’, resulting in widespread death and destruction. For hundreds of millions of people, everyday life was defined by political rituals mandated by the state-sanctioned Mao cult (Leese, 2011).

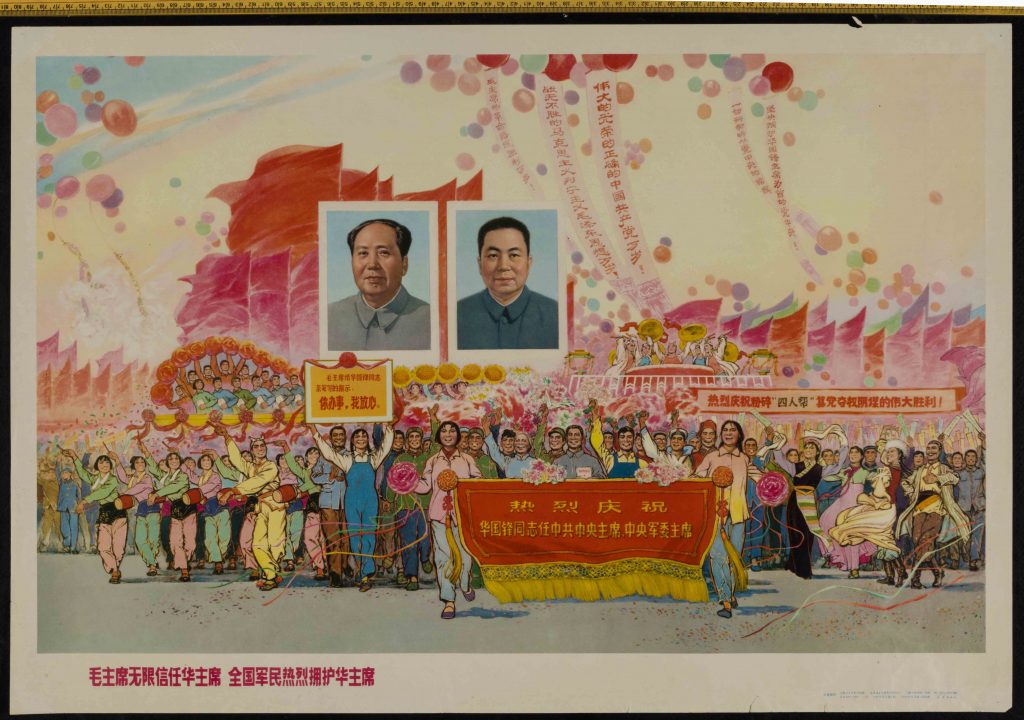

Fig 2. Jiang Nanchun (1976) Chairman Mao trusted Chairman Hua completely; the people and army warmly endorse him too. University of Westminster China Visual Arts Project.

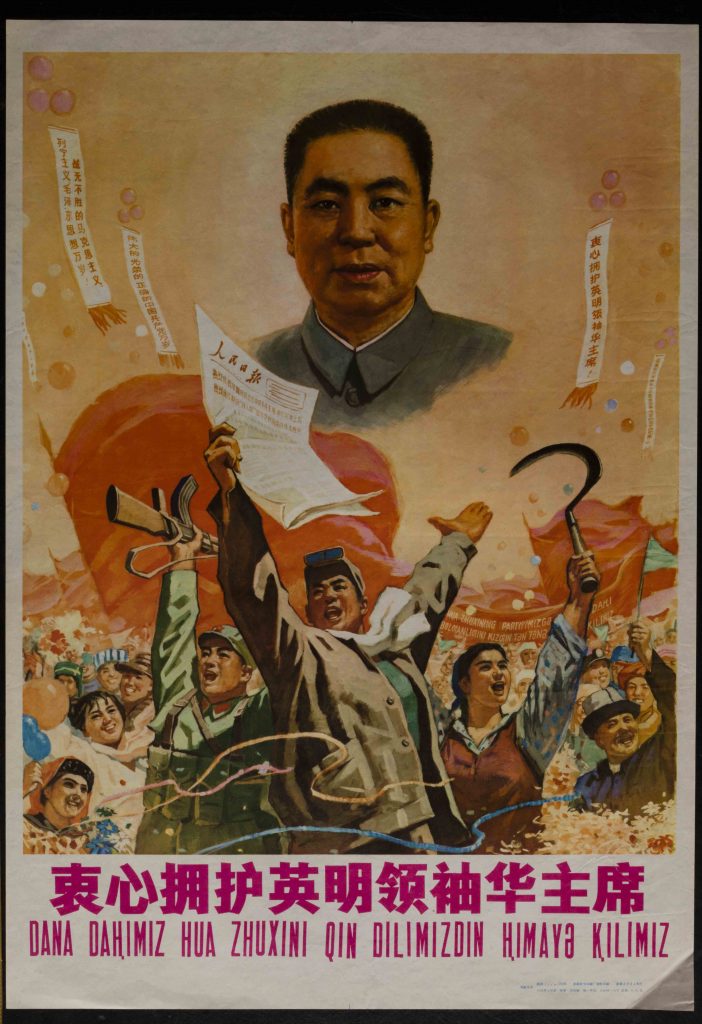

Mao died in September 1976, and the Cultural Revolution was concluded soon afterwards by his successor, Hua Guofeng. The elevation of the ‘wise leader’ Chairman Hua, as he was called in state propaganda, surprised contemporaries. The characteristically mercurial Mao had ‘chosen not to chose’ between the leaders of the left and right factions that had been locked in bitter struggle over the past decade. On taking power, Hua quickly ordered the arrest of the leftist ‘Gang of Four’, led by Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing. However, his rule was short-lived, and in December 1978 he was outmanoeuvred by Deng Xiaoping’s reformist faction. Deng became the paramount leader, while Hua was marginalised, retaining some official titles but little influence.

The period of Hua’s rule, from October 1976 to December 1978, has received little concerted attention from historians. In most historical surveys, this period is portrayed as a brief interregnum, warranting a paragraph or two at best as authors trace the origins of China’s four decades-long process of ‘reform and opening up’. The CCP’s 1981 ‘Resolution on certain questions in the history of our party’ praised his contribution to the purge of the ‘counterrevolutionary Jiang Qing clique’. However, it was savagely critical of Hua’s ‘two-whatever’s’ policy (to uphold whatever policy decisions Chairman Mao made, and whatever instructions he gave). In the most recently-promulgated resolution on party history (2021) Hua’s name is omitted entirely, rendering him an historical irrelevance.

Fig 3. Liu Nansheng (1978) Wholehearted support of the wise leader Chairman Hua. University of Westminster China Visual Arts Project.

Yet people living through the Hua era will have had little sense of what was to come. For many, the future looked as uncertain as the previous decade had felt. How can we, as historians, begin to approach the Hua era on its own terms? Exploring the material culture of this short-lived historical moment may provide some answers. In the ‘new’ history of the PRC that has emerged over the last decade, historians have placed great emphasis on the importance of everyday objects, as a corrective to approaches fixated on elite politics (Brown and Johnson, 2015). In the hands of ‘Sinological garbologists’ throwaway objects can allow us to understand how people navigated the everyday as the political climate changed around them.

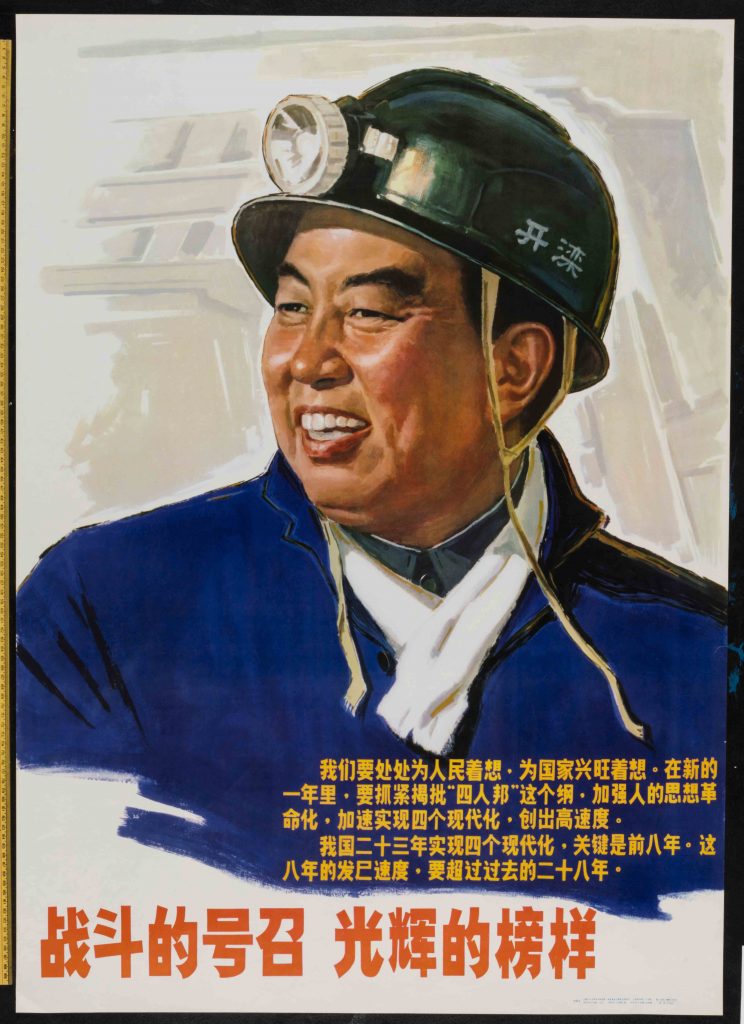

Fig 4. Ha Qiongwen (1978) Call to battle, glorious role model. University of Westminster China Visual Arts Project.

In this context, the 330-page Menus and Resources reflects two political projects from the Hua era that were aborted not long after its publication. The first is visible in the very words used to print the collection: in December 1977, the PRC embarked on a radical programme of Chinese character simplification to promote literacy. The scheme proved hugely unpopular and was stalled in 1978 before being formally abandoned in 1986. Some characters in Menus and Resources follow this second round of character simplification (the first took place in the 1950s). For example, the word egg (dan) is written as 旦 and not 蛋, and Gang (bang) from ‘Gang of Four’ is written as 邦 rather than 帮. However, the new scheme was only partially implemented in this book, with most characters remaining unchanged.

The second abandoned project was Hua’s programme of economic reforms. From 1977, Hua’s government began to promote the ‘Four Modernisations’ (of agriculture, industry, defence, and science and technology), drawing on an idea first espoused by Zhou Enlai in the early 1960s. Importantly, however, where Hua had envisioned the ‘Four Modernisations’ as a state-led project using central planning, Deng and his successors unleashed the power of the market to transform the economy under the same slogan (Tiewes and Sun, 2011). Nevertheless, the guide was meticulously compiled, and its publication represented a significant undertaking. The failure of Hua’s reform project and language reform were not foreseen when the book was produced.

Fig 5. Table arrangement for three people

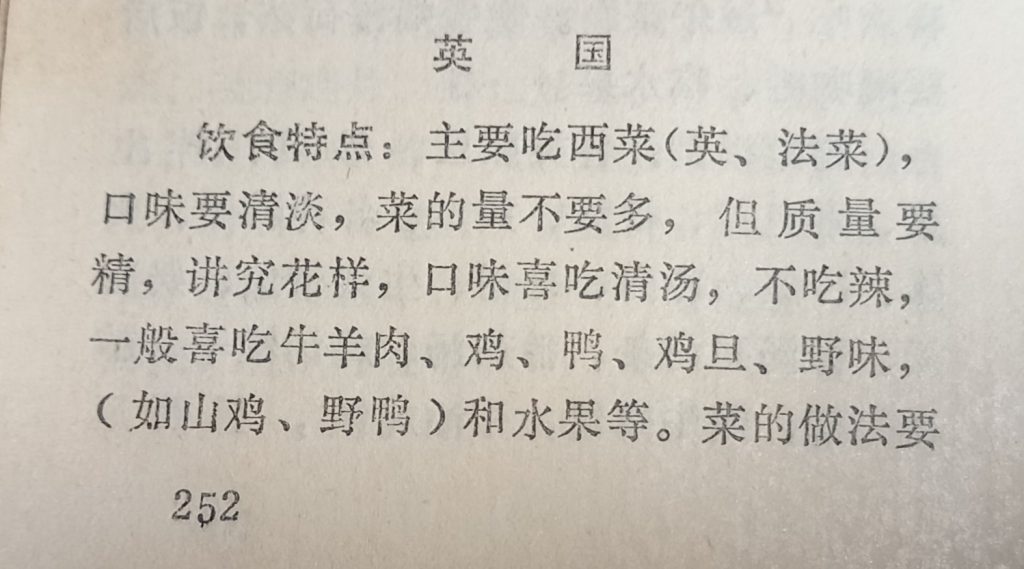

The book itself is divided into two main parts, the first of which contains recipes and cooking techniques for a wide range of Western and Chinese dishes. The second half details the culinary preferences and eating habits of foreigners of sixty different nationalities from every inhabited continent. The section on hosting Britons, to give one example, recommends serving well-presented and high-quality food, while avoiding strong flavours. It notes that British guests expected to be woken with a cup of tea in bed and that some would ask for afternoon tea (genteel eating habits more suggestive of English tastes in the 1930s than the 1970s). The guide also contains instructions for waiting staff on the manners foreigners expected, as well as illustrations for table layouts.

Fig 6. Section on hosting British guests

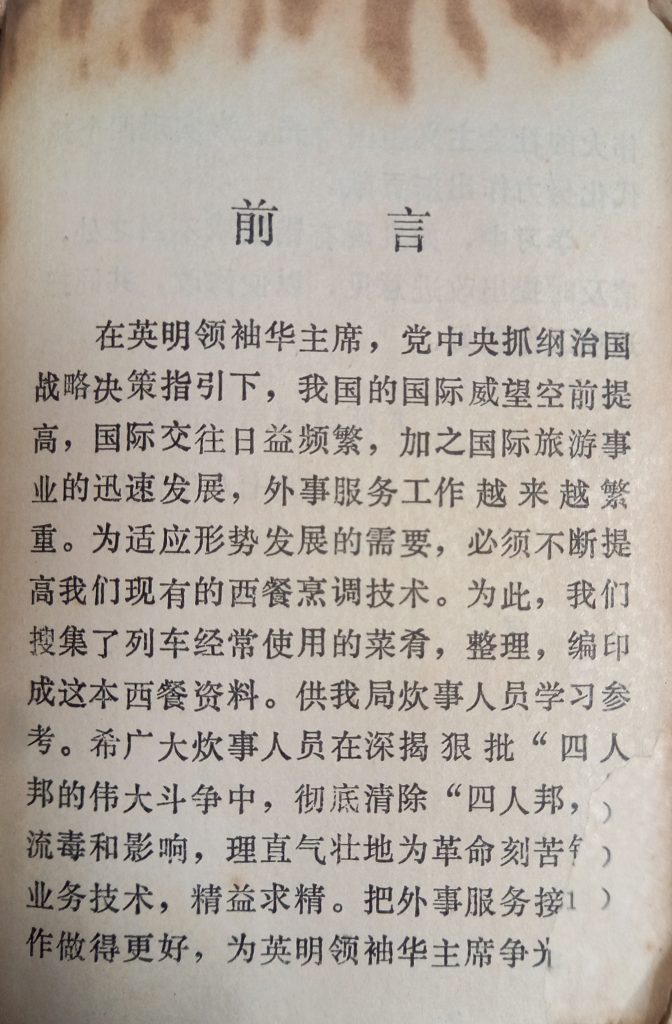

The care that went into the guide’s production demonstrates the importance attached to providing proper hosting, typical of the careful management of foreigners in the PRC (Brady, 2003). The foreword to the collection makes it clear that the dining carriage was expected to be a political space. Despite the Cultural Revolution having ended two years previously, politics continued to influence every aspect of life in China in the late 1970s, even when it came to preparing and serving food to foreign train passengers. As China embarked on the ‘Four Modernisations’, the number of foreign visitors was expected to increase. Accordingly, onboard catering staff were enjoined to perfect their cooking and hospitality to win glory for the socialist motherland under the wise leader Chairman Hua, and victory in the struggle against the poisonous ideology of the ‘Gang of Four’.

Fig 7. Foreword

The carefully-produced Menus and Resources speaks to the importance the Chinese state under Hua placed on post-Cultural Revolution ‘opening up’ in the name of modernisation. Perfecting the hosting of foreigners was important in late 1970s China. Hua’s ‘Four Modernisations’ project was abandoned but, as Menus and Resources shows, the Hua era was experienced by those who lived through it as the start of something new and not just an interregnum.

Jon Howlett is a Senior Lecturer in History at the University of York. He has published on a range of topics including: the political and social history of the PRC; Sino-British relations; the history of Shanghai; propaganda production; and decolonisation. He is a co-director of the York Asia Research Network. York staff profile. Twitter: @howlett_jj.

- TV Drama Discourse on Stay-at-home Fathers in China: Super Dad & Super Kids - January 28, 2022

- Freud and China - January 20, 2022

- “Cultural China 2020″—A Different Take on China - January 7, 2022

The book of Menus and Resources for Western Cuisine is very helpful to know how the railway system work amid the Cultural Revolution.