Written by Steven F. Jackson

Happy. Angry. Inspired. Grateful. The emotions expressed in Chinese propaganda posters between 1949 and 1990 were not subtle or complex, nor for all of the embrace of ‘socialist realism’ in communist art were they realistic. These posters, with their vivid reds, yellows, oranges, blues and greens were not Chinese people as they were — they were the Chinese people as they ought to be, at least according to the Communist Party. The fascination is that this proscriptive line in posters shifted frequently over the first four decades of the People’s Republic of China, and these artefacts can give us insight into this period for teaching, learning and research.

Founded in 1977 by writer and journalist John Gittings when we worked in the Chinese section of the Polytechnic of Central London (PCL), the China Visual Arts Project at the Contemporary China Centre of University of Westminster has assembled an impressive collection of over 800 of these posters and posted them to the university archive site. The site is searchable and categorized based on Gittings’ original 17 thematic categories. The collection is an invaluable tool for teaching about modern Chinese history and politics, as well as about the political role of visual arts in societies.

In this blog, I describe three core ideas that emerge across the collection and reflect on their pedagogical value in the classroom.

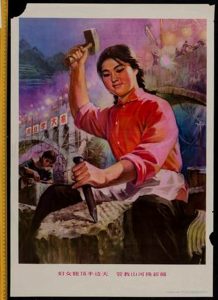

1.Transforming Society. Revolutionary governments seek to change the societies they govern, to make a break from the past and to create new, ideal citizens. Social relations, such as gender and age are challenged. A good example of this can be seen in the quiet confidence of the face of the woman in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1: Women can hold up half the sky (1975), by Wang Dawei. Source: University of Westminster’s China Visual Arts Project.

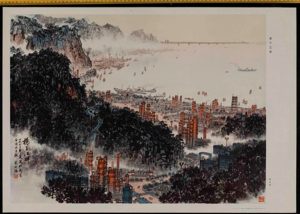

2.Transforming Nature. Another aspect of communist societies (and indeed many societies prior to the 1970s) was the relationship of people to nature. In contrast to the near-universal concerns for the environment in the 21st century, Chinese posters showed a frequent theme of transforming nature for humanity’s benefit. The second title of the ‘Women hold up half the sky’ post is ‘Surely the face of nature can be transformed.’ The next poster – ‘The bank of the Yangzi river’ (Fig. 2) is particularly interesting because it uses a traditional shan-shui山水 ink wash painting technique for a familiar theme – the Yangtze River – but the banks of the river are now crowded with petrochemical facilities, an old-fashioned medium for a modern message: the river and its banks are being used for industry.

Fig. 2: The bank of the Yangzi river (1973), by Song Wenzhi. Source: University of Westminster’s China Visual Arts Project.

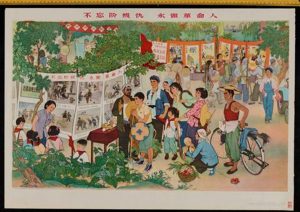

3.Recalling the Revolution. Fifteen years after the 1949 revolution, Chairman Mao Zedong realized that a new generation was growing up that had no memory of pre-revolutionary China or the conditions that gave rise to the communist party. The poster ‘Don’t forget class struggle, forever make revolutionary people’ (Fig. 3) was part of a party effort to remind the new generation of that legacy. The central figure, a peasant man speaking earnestly to the fresh-faced youth uses posters to show what had happened. Thus, the poster is about revolution, but also depicts posters and their use.

Fig 3: Don’t forget class struggle, forever make revolutionary people (1964), by Chen Mou; Shu Dong. Source: University of Westminster’s China Visual Arts Project.

Chairman Mao, however, wanted more than posters to create a new revolutionary generation; he wanted the youth of China to take action against what he regarded as the parts of China’s leadership who were ‘revising’ communism into something else, and thus he launched the Cultural Revolution. About one quarter of the collection covers this period (1966-76), and these are quite distinct. Unlike posters from the previous political campaigns in which smiling workers, grinning peasants, and stalwart soldiers are constants, the Cultural Revolution faces show anger and defiance, bravery and suspicion. Fig. 4 shows an example of the period, where we see workers, peasants and soldiers, and the central figure of a Red Guard, one of the youth Mao recruited to ‘make revolution.’

Fig. 4: Revolutionary proletarian right to rebel troops unite! (1967), by unknown artist unknown. Source: University of Westminster’s China Visual Arts Project.

Pedagogy. Posters are natural discussion and essay prompts, and I have used several as quiz prompts for years. In class, I usually employ the simple opening technique of showing (via PowerPoint) a poster, and asking students to look at it for about two minutes, and then they make comments using ‘I like…’ ‘I noticed…’ and ‘I wonder…’ as the prompts. A more detailed questionnaire is also used for the two-day version of the in-class discussion assignment.

Naturally, a little context for these posters is necessary for students who were born decades after the tumultuous periods of Chinese history from 1949 to 1990. After the Communist Revolution in 1949 there were multiple political campaigns such as the Great Leap Forward (1958-61), and the Cultural Revolution (1966-76) and a dozen or more shorter and more specific campaigns. It helps that many of the posters at the China Visual Arts Project website have dates to help place the pictures in the context of specific campaigns or events. The posters’ text is also translated so that the phrase is clear (though not always the meaning).

Targeting an often semi-literate audience, the symbols used in the posters were usually quite simple: wrenches and gears or blue overalls indicate workers; uniforms show soldiers, sheafs and hoes show peasants, (what I dub the ‘holy trinity’ of Maoist iconograph). Peasants in these posters are often shown wearing turbans, a common head covering among Han Chinese which some may mistake for ethnic minorities. Workers are often shown with iron and steel workers’ furnace observation glasses. A fourth figure begins to be seen in posters after 1976: a scientist or ‘intellectual’ who is always shown wearing eye glasses. Age was usually depicted by heavier facial lines and beard shadows for men, hair in a bun for women.

Posters also are an opportunity for critical thinking, and nowhere is this more needed than the common posters involving China’s 56 ‘official’ ethnic minorities, such as the 1975 poster ‘Long live the unity of every nationality in this country!’ (Fig. 5). The poster is remarkable in that it is a reproduction of a photograph, which is rare among Chinese posters of the period, though quite common for Soviet posters. Enthusiastic and grateful minorities are always shown in their distinctive national costumes, and a Tibetan woman wearing a pangden (brightly-coloured apron) is invariably included. Mongols can be identified by wearing the deel, a caftan garment, Koreans are invariably women in hanboks. Other minorities such as the Miao and Yi are depicted with their distinct dress. The typical portrayal is of a large group of minorities, with Han Chinese posed in the middle, all linking arms, grinning broadly and gratefully to be part of the People’s Republic of China. Given the news out of Xinjiang of late about the treatment of Uighurs, students quickly recognize that the propaganda and the policies don’t match.

Fig. 5: Long live the unity of every nationality in this country (1975), by unknown artist. Source: University of Westminster’s China Visual Arts Project.

Steven F. Jackson is professor of political science at Indiana University of Pennsylvania. He writes primarily on Chinese foreign relations. He began his interest in Chinese revolutionary posters in 1980 as a student, and acquired more while teaching English in China 1981-83.

- TV Drama Discourse on Stay-at-home Fathers in China: Super Dad & Super Kids - January 28, 2022

- Freud and China - January 20, 2022

- “Cultural China 2020″—A Different Take on China - January 7, 2022