Written by Freja Howat

Working over a period of five months in 2018-19, I joined the Records and Archives team at the University of Westminster to help implement the digitisation and digital preservation of its collections. Founded as the UK’s first polytechnic institution, the University has collections spanning over 170 years. My role was, needless to say, varied.

When I told people that I worked in an archive, most people imagined me sat among a load of boxes in a dark, dusty strongroom. This was partly true, but popular visions of archives are based on myths that do not do service to the active labour that goes into providing access to collections via outreach and digitisation. Archives are not static repositories – the work around the University’s Chinese Visual Arts Project exemplifies this point.

Founded in 1977 by the writer and journalist John Gittings, then Senior Lecturer in Chinese at the Polytechnic of Central London (now the University of Westminster), the collection comprises a staggering 843 posters acquired from Hong Kong and mainland China, dating from the 1940s to the 1980s, alongside a wealth of books, objects and ephemera. The collection was used and built upon as a teaching aid for the Polytechnic’s classes in Chinese language and politics and is still used today for similar purposes by Senior Archivist Anna McNally for a range of courses at the University of Westminster engaging with visual and material cultures. I worked with Anna to deliver outreach sessions designed to offer students a deeper understanding of the ways in which archives are constructed, and how collections are attributed with meaning and value.

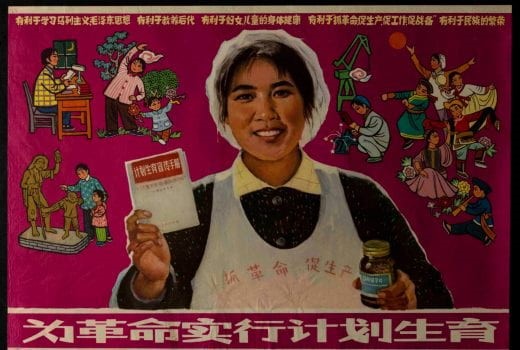

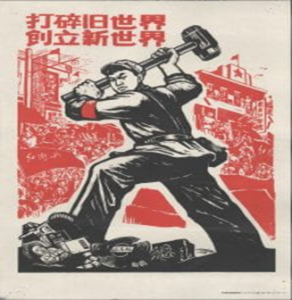

These sessions often engaged with the propaganda posters, which encompass a wide range of styles, responding to the frequent changes in the political climate. Created in the red and black graphic woodblock style that has become so synonymous with the Cultural Revolution, posters such as “Smash the old world and build a new one” (1967) [Fig. 1] portray the elimination of China’s old traditions under the Communist regime. By the mid-1970s, these posters begin to shift in style. More posters began to promote healthcare, education and industry such as “Put birth control into practice for the revolution” (1974) [Fig. 2], a message that took on new significance following the introduction of the one child policy (1979-2015).

Figure 1: Item CPC/1/E/39 – Unknown Artist, Smash the old world & build a new one, 1967, 270mm x 376mm, Records and Archives, University of Westminster

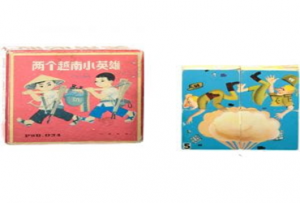

Accompanying these posters are a number of propagandist toys such as a puzzle cube of Vietnamese children planting a bomb for American soldiers [Fig. 3] and a pair of dolls that depict the Red Guards, a mass paramilitary social movement mobilised by Mao in 1966 and 1967, during the first phase of the Cultural Revolution [Fig. 4]. There are also objects that detail the everyday, such as bus tickets and receipts; pins featuring Mao; matchbooks depicting Chinese monuments and lingerie [Fig. 5]. These materials have received less interest than the posters, yet they resonated with me as I felt they had just as much to say about the culture and politics of China during this period.

Figure 2: Item CPC/1/H/8 – Unknown Artist, Put birth control into practice for the revolution, 1974, 776mm x 542mm, Records and Archives, University of Westminster.

Whilst considering the transformation of political narratives overtime, students also reflected on the wider context by which the collection was formed and how it portrayed China from Western perspectives. It is for this reason that I became involved with digitising this aspect of the collection; to increase the visibility of the collection as a whole, which when seen in its wider context as a teaching aid also raises questions about what was then the Polytechnic of Central London; Why were these materials collected?; How and why did they inform study about China and its peoples? Questions surrounding the nature of the collection and how it came into being continue to grow and evolve as the collection is catalogued, distributed and engaged with.

Figure 3: Puzzle cube, c.1970, Records and Archives, University of Westminster

I set to work photographing these objects and played around with 3D modelling. Although we thought it could be an interesting way for researchers overseas to get an idea of the materiality of an object [Fig. 6], producing 3D models was not without its issues. Firstly, a 3D model does not replace the materiality of engaging with an object first-hand; secondly, not everyone has the expenses or access to a machine that is powerful enough to produce or view 3D models. This led me to think about lower tech solutions such as .gif making; accessible to anyone with a mobile phone. Without being able to physically handle the materials first-hand, this would at the very least improve access to the collection. In addition to this, the University of Westminster has recently implemented a new online catalogue which enables users the choice between English and Chinese. This is a development that will fundamentally alter the ways in which audiences engage with the collection and how it is managed.

Figure 4: Red Guards, c.1967, Records and Archives, University of Westminster

By considering the ways in which this collection has been acquired and the channels by which it continues to be distributed, audiences are offered a new context for viewing the collection. It allows us to think critically about the appropriation of the word ‘archive’, about differences between digital and physical objects, and also about the accessibility of material and the impacts of digitisation on non-European collections that have been attributed Westernised standards of archival value.

Figure 5: Bra, c.1966-1976, Records and Archives, University of Westminster

Figure 6: Work in progress 3D Model of Red Guard Doll, Records and Archives, University of Westminster.

Freja Howat is currently a CHASE Doctoral Researcher at the University of Sussex looking at DIY communities, digital curation and archiving in the Middle East. During her undergraduate studies at the University of Brighton, Freja was employed in digital preservation as part of the Chinese Visual Arts Project Archive, University of Westminster. All images featured are courtesy of University of Westminster Archive. A version of this piece was previously published on the History of Art and Design Blog, University of Brighton.

- TV Drama Discourse on Stay-at-home Fathers in China: Super Dad & Super Kids - January 28, 2022

- Freud and China - January 20, 2022

- “Cultural China 2020″—A Different Take on China - January 7, 2022