Written by Philipp Demgenski

In early 2017, I joined the UNESCO Friction Project and set out to study how the UNESCO 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity is implemented in China. In this post I reflect upon some of my experiences and findings.

The 2003 Convention defines Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) as “the practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, skills – as well as the instruments, objects, artefacts and cultural spaces associated therewith – that communities, groups and, in some cases, individuals recognize as part of their cultural heritage” (UNESCO 2003: Article 2). Accordingly, cultural heritage is not (only) material, fossilised and monumental, but dynamic and subjective. Also, it is the so-called “heritage bearers” and not experts who are to define heritage, imbue it with meaning and value and work towards its safeguarding and management. By focusing on heritage communities, on ideas of participation and self-representation, the founding fathers of the 2003 Convention also particularly envisioned this convention as a tool for good governance and the protection of human rights.

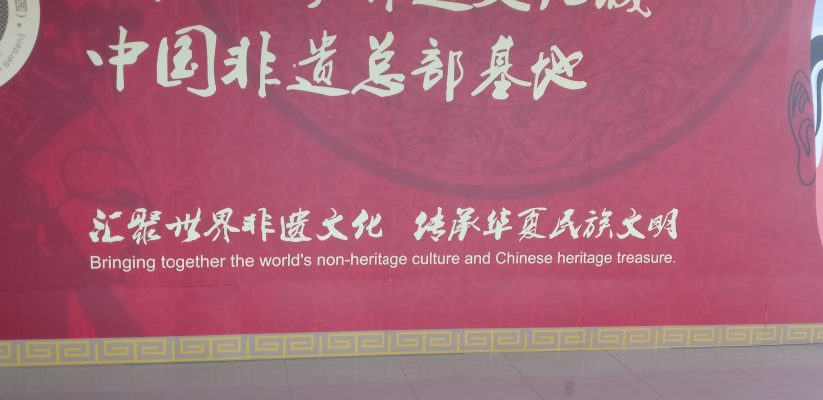

China was among the first countries to ratify it in 2004. Since then, impressive amounts of ICH elements have been identified domestically, legal texts have been devised and the ICH concept has found much resonance in the media and among the general public. China was also quick in setting up its own administrative and institutional framework. It now has a comprehensive national inventory system for ICH elements at four administrative levels (national, provincial, municipal and district/county) and an additional four-tier inventory for so-called “Representative ICH Transmitters,” (daibiaoxing chuanchengren). Locally known as feiyi (lit. “non-heritage,” see photo), ICH is indeed everywhere, especially when one actively looks for it. During fieldwork, I found it at airports, in train stations, shopping malls, on mobile APPs, in the media, in specially designed ICH expos, in academia and, above all, in political discourse. I heard many proud remarks about China being particularly rich in ICH. Bringing up ICH seemed like a cue for people to ascertain that ICH and China are like chalk and cheese, they simply belong together. A Chinese folklorist who also advises the government on ICH matters once told me: “Normally, it’s always either the people that are not happy about the government or the government that is not happy about the people. Only in ICH, everyone is always happy: government, scholars, people.” As of early 2020, China has 40 elements inscribed in the UNESCO ICH lists, more than any other country.

There are a number of reasons for this “ICH fever” (feiyi re). The 2003 Convention and with it the ICH concept entered China precisely at a point when notions of “traditional culture” (chuantong wenhua) or “folk customs” (minsu) re-emerged in the political and public discourse, after having been under attack during the Cultural Revolution and largely ignored during the early “reform years.” In 2002, then President Jiang Zemin famously called for “the protection of major cultural heritage and outstanding folk arts” and hereby heralded the beginning of a new identity for cultural heritage as not being antithetical to, but very much compatible with the goals of economic growth and modernisation. ICH presented the state with a distinct value framework to appraise, control, but also to legitimise many cultural practices and traditions that were previously discarded as undesired superstitions. Under this newly gained umbrella of legitimacy, officially-endorsed ICH could then also be exploited for the growing domestic tourist industry and the increasing desire of people to travel and consume “culture.” Especially in recent years, ICH transmitters have been urged to innovate and tailor their respective products to market demands; there now exist a number of mobile APPs that sell ICH products as luxury goods. Internationally, the introduction of ICH has allowed China to further engage in cultural diplomacy, consolidate its soft-power and to spread a specific image of “cultural China” around the globe; being a member of an international legislation has also helped the state to legitimate policies at home.

It is clear: ICH matters in and to China and it is ubiquitous in everyday life. But looking at domestic understandings, both on the level of legislation and public discourse, there exists a rather stark discrepancy vis-à-vis the UNESCO definition described above. A scholar and ICH advisor to the Ministry of Culture and Tourism once even told me that “ICH in China is not actually ICH.” Rather than defining ICH as something ephemeral, mobile and spontaneous that belongs to the communities whose heritage is at stake, China’s own ICH Law from 2011, for example, “is formulated for the purposes of inheriting and promoting the distinguished traditional culture of the Chinese nation…” The law also refers to the idea “authenticity” (article 4), which had deliberately been excluded from the 2003 Convention. Chinese ICH is, in fact, conceptually much closer to the World Heritage Convention from 1972 and allows for external actors (scholars, officials) to evaluate and authenticate heritage. The law is also largely void of the key ideas of community participation, merely stating that “the State shall encourage and support its citizens, legal persons and other organizations to participate in the work concerning the protection of intangible cultural heritage” (article 9, emphasis added). Someone closely working with the Ministry of Culture once stated half-jokingly that “in China, if they don’t control or regulate you, your participation is already quite significant,” explaining that the idea of community participation is really only something understood and used by experts who have a good grasp of heritage terminology (Bortolotto et. al 2020). Generally and little surprisingly, Chinese ICH is essentially a matter of the state. In the absence of the political ideals of good governance and human rights that permeate the discourse at UNESCO, Chinese ICH is largely reduced to a general idea of “culture” and even though many actors involved in the ICH field see the need to “keep this culture alive,” it is essentially the state that not only decides how this should be done, but also what ICH is and who it belongs to.

At the same time, recalling the above quote about everyone in ICH being happy, the introduction of this concept has also been an enabling and empowering force. For example, many practitioners and official ICH transmitters in China conveyed to me that they are indeed happy about the existence of the ICH framework, that they feel “more recognised” and, most commonly-heard, that ICH has allowed them to earn money and make a livelihood from their cultural practices to a degree that was not possible before. So within the broader political economy of China, we may say that ICH has provided many practitioners with an opportunity to participate in and benefit from national economic development and modernisation. This form of participation may be different from that envisioned by the 2003 Convention, but it would be erroneous to jump to the conclusion that China’s “take” on ICH is somehow wrong. After all, even though politics are often seen as standing in the way of genuine safeguarding and preservation work (ironically often by those who most passionately believe in the political potential of the 2003 Convention), ICH is by definition political and it is also never neutral. When cultural practices and traditions are “diagnosed” as ICH, they are subject to a new value system, which is inevitably also transformative, whether in China or elsewhere. How this transformation takes place and what it looks like can only be evaluated within specific socio-political and cultural contexts. Maintaining this degree of detachedness has, however, been the biggest challenge in my fieldwork as I was always treading the narrow path between “UNESCO extremes” and “China extremes.”

Philipp Demgenski is Junior Professor at the Anthropology Research Institute, Department of Sociology of Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China. He is currently working on a project titled “UNESCO Friction: Heritage-making across global governance,” which looks at the implementation of the UNESCO 2003 Convention in China, Brazil and Greece. He is also the vice secretary of the Intangible Cultural Heritage Research Centre of Zhejiang University. He obtained his PhD in Anthropology from the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Between 2012 and 2015, he conducted a total of 18 months of ethnographic fieldwork on inner city redevelopment and urban heritage in Qingdao. He is currently writing a book on this topic. Image credit: author.

- TV Drama Discourse on Stay-at-home Fathers in China: Super Dad & Super Kids - January 28, 2022

- Freud and China - January 20, 2022

- “Cultural China 2020″—A Different Take on China - January 7, 2022

[…] the second piece, Philipp Demgenski takes a look at intangible cultural heritage practices, with a particular focus on how the UNESCO […]