Written by Gina Tam

This excerpt is from my book Dialect and Nationalism in China, 1860-1960. The book centers the history of the Chinese nation and national identity on fangyan – languages like Shanghainese, Cantonese, and dozens of others that are categorically different from the Chinese national language, Mandarin. I trace how, from the late Qing through the height of the Maoist period, fangyan were framed as playing two disparate, but intertwined roles in Chinese-nation building: on the one hand, linguists, policy-makers, bureaucrats and workaday educators framed fangyan as non-standard ‘variants’ of the Chinese language, subsidiary in symbolic importance to standard Mandarin; on the other hand, many others, such as folksong collectors, playwrights, hip-hop artists and popular protestors, argued that fangyan were more authentic and representative of China’s national history and culture than the national language itself. These two visions of the Chinese nation—one spoken in one voice, one spoken in many—have shaped the shared basis for collective national identity for over a century, and their legacies are still significant to the ongoing construction of nationhood today. The section below looks at these contemporary legacies, examining how PRC language policy today reflects a long-established state-driven emphasis on the political, cultural, and linguistic hierarchy between Chinese fangyan and the Chinese national language.

In 2003, a local journalist filed a report on language reform in seaside Qingdao. The largest city in Shandong province, it is known among linguists as a distinct branch of the Guanhua dialect region – mutually intelligible with Putonghua, the Chinese national language known commonly as Mandarin, but unique in its phonetics and tones. The journalist was tasked in measuring the effects of Putonghua promulgation by interviewing a line of workaday bank tellers, hotel concierges, and nurses. “Why are you not speaking Putonghua?” the reporter asked a bank teller incredulously. The equally perplexed man stated, “I am speaking Putonghua, no?” She moved on to a handful of middle-aged workers, demanding to know why they did not speak in the national language. These things come slowly, they maintained with a hint of defensiveness. Some remained confused as to why a journalist would challenge their claims about the language they were speaking. Still others simply laughed sheepishly at her questions. In concluding the piece, the journalist interviewed a younger Qingdao resident, who, in perfect Putonghua, expressed outrage over falling standards. If its residents cannot properly speak the nation’s common language, she asked, “how could Qingdao claim to be a modern city, ready to be featured on a global stage?” Qingdao, the two summized, was falling short of its responsibility to properly represent the Chinese nation.

This report, a bizarre mix of investigative journalism and public shaming, had a clear message: speaking Putonghua was an expectation for being part of modern Chinese society. Its message also poignantly reflects current government priorities. While the PRC’s government deemed Putonghua the national language in 1956—defined as “Beijing’s pronunciation as standard pronunciation, Northern dialect as the base dialect, and modern vernacular literature as standard structure, vocabulary, and grammar”— the push for Putonghua promulgation became more targeted, ubiquitous, and aggressive in recent decades. The 1982 constitution declared that the state was responsible for promoting Putonghua as the nation’s language, paving the way for a series of local and national policies targeting education, public service, and art. Today, Putonghua is taught in all schools, dominates public announcements, and is the sole focus of language learning initiatives abroad. Teachers and broadcasters are required to pass a Putonghua proficiency exam with high marks. These measures have been matched by crackdowns on non-standard language use in the early 2000s. Local policies targeted improper use of pinyin or traditional characters on street signs. In 2001, an announcement from the Department of Education designated Putonghua for public use, and other non-Chinese languages, called fangyan in Chinese, for private use. In 2005, a new media law sought to eliminate overly vernacular language and code-switching. While content performed entirely in some fangyan is permitted in certain contexts, journalists, media personalities and actors are no longer permitted to pepper their language with phrases or slang from other tongues.

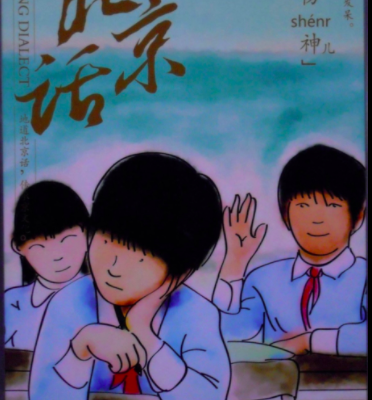

It would be easy to interpret these policies and accompanying media reports as state attempts at linguistic erasure. Despite laws explicitly permitting fangyan use, it is entirely unambiguous which one the state sees as the national representative. Yet other evidence imply that the central government has not attempted to eradicate fangyan entirely. In contrast, local governments, with support from Beijing, have unveiled events meant to “save the dialects” from the fast-paced urbanization threatening the vagaries of local culture. In Suzhou, some primary schools, in collaboration with a “Suzhou fangyan training center,” began experimenting with short daily lessons in Suzhou fangyan. In Beijing in 2014, the subway was adorned with public service announcements teaching passersby vocabulary particular to “Beijinghua” (or ‘Beijing-ese). In 2015, the city of Leizhou, in conjunction with hot-sauce syndicate Modocom, hosted its first annual “Zurong Fangyan Film Festival.” Offering awards for films made exclusively in Chinese fangyan, they summarized their goals in a short sentence: “Zurong Village Dialect Film Festival from beginning to end expressed the following idea: Love fangyan, love cinema, love home.” Chinese academia has also contributed to these efforts. In 2013, the State Council’s National Social Science Fund of China approved a research project to create a “sound digital database of Chinese fangyan.” The database, designed to “save” China’s fangyan, is guided by the belief that it is the responsibility of the scholars and the state to protect their nation’s heritage.

While at first blush these “save the dialect” measures seem at odds with state efforts to promulgate Putonghua, I argue that both serve the same underlying goal: the promotion of a stark hierarchy between a standardized national language and all other Chinese fangyan. The hierarchy between national language and fangyan in China has its roots in the late nineteenth century. In the final years of the Qing dynasty, a state beleaguered by foreign imperialism and domestic turmoil, modern Chinese elites proclaimed that the nation’s survival depended upon its ability to transform into a modern nation. For many of them, modern nations had a national language, and a lack of one was seen as proof of China’s lack of national modernity. After decades of debate about the constitution of such a national standard, in 1925 reformers designated Beijing’s language as the national standard; in so doing, what had once been one fangyan among many was suddenly transformed into the sole linguistic representative of the Chinese nation. The language’s unique political status quickly seeped into the discourse of elites and the structures they built, quietly reinforcing and normalizing the notion that the national language, because of its relationship with modern state-building, stood apart from all others. And as evidenced by the report from Qingdao and the policies it supports, the legacies of these earlier discourses still inform state actions today. By seeking to outlaw code switching and seamless mixing, or demonstrating disdain towards poorly-spoken Putonghua, the state and its affiliates continue to promote the strict hierarchical separation of Putonghua and fangyan just as their predecessors had done.

Fangyan preservation efforts also reinforce that same hierarchy. These measures are not meant to make fangyan serve the same communicative, cultural, or subjective roles as Putonghua; rather, they are geared towards preserving them solely as historical legacies. This framing has roots in early PRC language policy. After the Communist revolution of 1949, scholars associated with the new state began to justify the promulgation of a standard language—and the framing of fangyan as subsidiary branches—through a Stalinst model of history and language. This teleological view of history saw languages as direct representatives of the communities that spoke them, and maintained that only national languages could “progress and develop,” whereas dialects could only be remnants of a stagnant past, curios to be placed in museums. “Save the dialects” activities today reflect this view of history, presenting dialects as part of the nation’s history but only significant insofar as they contribute to a teleological narrative of eventual national unity. Even those advocating for the preservation of Suzhou fangyan confirmed this distinction: “Putonghua and fangyan, one is our country’s common language and script, the other is an important linguistic resource.”

In short, aggressive Putonghua promulgation strategies, including though certainly not limited to on-camera shaming, exalt Putonghua as the national language, while measures to “save” China’s dialects subtly institutionalize fangyan exclusively as local cultural heritage. These policies are but two sides of the same coin. They draw a clear divide between the language that serves as national representative, and local manifestations of that national culture that should be preserved for posterity and little more. As the state and its allies have actively promulgated Putonghua as an archetype of Chinese national identity and carefully curated fangyan as little more than data, heritage, or private curiosities, the apotheosis of the hierarchy between national language and fangyan lives on.

It is critical to remember that the implications of these policies extend far beyond language. Designating fangyan as subsidiary “dialects” and Putonghua as the “common language of the Chinese people” implies that Putonghua can represent a unified sense of national identity and citizenship in a way that no fangyan could. Our Qingdao journalist and our “save the dialect” afficionados are not simply concerned with linguistic taxonomies —it is a hierarchy of identity they wish to maintain. And in their actions, they ultimately reinforce today’s vision of Chinese identity under the current PRC state: an essentialized, homogenous identity where other representatives of national identity are held as subsidiary to the state-defined standard.

Gina Anne Tam is an Assistant Professor of Chinese History at Trinity University in San Antonio, Texas. You can purchase her book, Dialect and Nationalism in China, 1860-1960, here. Image credit: Subway poster from ‘Save the Dialects’ movement, photographed by author in 2014.

- TV Drama Discourse on Stay-at-home Fathers in China: Super Dad & Super Kids - January 28, 2022

- Freud and China - January 20, 2022

- “Cultural China 2020″—A Different Take on China - January 7, 2022

[…] second piece, written by Gina Tam, explores linguistic hierarchies and Mandarin promulgation. Tam discusses how PRC language policy […]

To be fair, creating a hierarchy with a “national language” above local dialects is what the vast majority of modern nations have done. It’s already something if the state doesn’t actively try and discourage people from speaking in dialect at all (although that may well happen soon).