Written by Cassie Lin

As a research student often looking at feminist movement and theories, I am quite familiar with its history in the modern western world. But what about China? What happened to women’s rights in China back in the day, especially when they were probably facing more challenges than their western comrades, due to war, poverty and suppressing feudalist values?

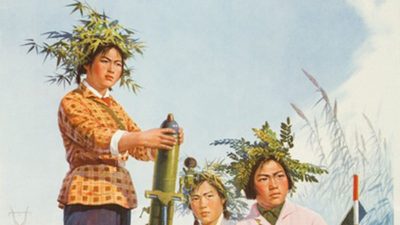

I found some clues in the poster collection – there were images of women carrying artillery troops and machine guns, women portrayed as factory workers and engineers, they were the so-called “Iron Girls” in the first few decades of Communist China (50s – 80s), and largely appeared in propaganda campaigns. These tough-and-masculine-women portrayals remind me of the famous American wartime poster “We Can Do It!”, both similarly served the purpose of lifting national spirit and boosting worker morale.

“Miliatiawomen in the Paracel”, 1975

Raising women’s right was a significant theme of the revolutionary propaganda in China from the 1950s to the 1970s. Attempting to achieve gender equality is considered as one of the least controversial legacies of Mao ZeDong. As an inspiration, his celebrated quote “women hold up half the sky” was widely promoted across the country. Rumour says the statement was made to respond an article published on a local Women’s Federation Magazine in Gui Zhou province in 1955. As women has become a valuable work force in China’s rapid industrialisation development, the article proposed equal pay for equal work between men and women. Interestingly, at the same time, the second-wave feminist movement was taking place across the pacific ocean, and the feminist symbolism in “women hold up half the sky” even received affirmation from western left-wing intellectuals.

“Women Hold Up Half the Sky, the Face of Nature is Transforming”, 1975

As part of the revolutionary movement, policies and laws were made to protect women’s right in marriage and education. In 1950, the New Marriage Law (also known as the First Marriage Law) was passed in China. It radically changed the existing patriarchal marriage traditions, such as arranged and forced marriage, concubinage and prohibition for women to seek divorce. Nevertheless, the gender gap for primary and secondary education was decreasing at the time, and women were encouraged to strive for more educational opportunities.

“Studying at Night”, 1974

Enough of the boring historical facts, how is the women’s liberation movement actually influences each individual in China? I’m trying to compare the life status between three generations of women in my family here, for some possible evidences.

Starting by my beloved grandmothers – Grandma Liang, from my father’s side, arranged to marry her husband, fought in the civil war, and was offered an official’s position in the local government when the war ends. She had to turn down the offer as she was never properly educated and was unable to read. She doesn’t know how to speak Chinese mandarin (the official language) and I can only communicate with her in dialectic Cantonese. The furthest place she ever travelled to in her life is the capital city of our province. Grandma Chen, from my mother’s side, arranged to marry her husband, and didn’t even know what he looked like until the wedding night. After the establishment of Communist China, she attended night schools and learned how to read and write, she was already a mother to four children by then. She enjoyed reading newspapers, watching sports and loved to criticise my taste in fashion. Luckily, both of my grand mothers escaped the suffering of feet binding (Chinese custom of applying painfully tight binding to the feet of young girls to prevent further growth).

Coming to my mother, growing up during the 10-year Cultural Revolution (a national movement to preserve “true” Communist ideology by purging remnants of capitalism and traditional elements in Chinese society from 1966-1976), she was influenced by its aftermath and joined the army at the age of 18. She served in the air force for five years and was trained in radio operating. After discharging her military service, she was assigned to become a librarian. She had a monthly library budget and was able to purchase a large amount of western literatures. She enjoys Agatha Christie more than Conan Doyle. She later attended the reformed Adult University Entrance Exam and received a degree in Philosophy. She met her husband through her flatmate in university. After graduation, she started to work for a department in the local government. She was responsible for dealing with issues relevant to labour, youth and women’s rights. She considers herself having a greater career achievement than most women in her generation and now happily retired. Her current hobby is travelling, she just returned from Russia, and planning to go to Australia and New Zealand next month.

“Lofty Aspirations reach the Sky”, 1973

And then it’s me, from the youngest generation of the family, attended primary and secondary schools under the policy of 9-Year-Compulsory Education in China, and developed a personal interest in music and film during my teenage days. I was super into British indie bands in high school and wrote a few reviews for a music magazine. At the age of 18, I came to the UK for university, film studies and related subjects have been my major all along. I am able to form a lot of international friendships and enjoy the multi-cultural scene in London a lot. I tried to learn German for a while but failed, then I figured English is quite enough for a second language, at least for now.

“Free from Tedious Domestic Chores, Devote Yourself into Socialism Construction “, 1960

It is fascinating to see how things have changed for women in China (or at least for those ones in my family) over the last 100 years. My mum still talks about the liberatory movement for women as if it’s one of her fondest memories, even though she also admits women in China have to suffer a double burden, as they are still expected to handle domestic chores while preforming to the same professional standards as men in their work place. The idealism behind “Women Hold Up Half the Sky” may seem a bit redundant at this post-feminist era, however, it cannot be denied, the social development behind such ideology did radically improve the status of women in modern China. There is still a long way to go, but, one step at a time.

“妇女能顶半边天”

目前所做的研究课题需要时常接触有关女性主义的理论书籍,致使我对西方世界的女权运动历史有一定系统的了解。相比之下,关于发生在中国的女性解放进程,却只有一个模糊的印象,大概是由于中国女性所面对的道德压抑与社会挑战,比她们的西方盟友们更为艰难,也更为复杂,所以很难通过相同的方式进行解读。

在整理中国宣传画收藏的过程当中,我留意到许多以妇女解放为主题的宣传画。画中女性被刻画成坚毅而阳刚的模样,或是身背步枪的西沙女民兵,或是在潜心学习如何使用迫击炮的女炮班成员,又或是在工地凿石造渠的女工,而搭配的标语大多时“妇女能顶半边天,管教山河换新颜”这样的口号,一反传统观念里柔弱的女性形象。

“妇女能顶半边天”的名言,即使对于我们这一代中国青年来说,仍然是有一些耳熟的。据说,其缘由来自贵州妇女联合会刊物发表的《在合作社内实行男女同工同酬》一文,用以表彰第一个实行男女同酬的村庄。毛泽东看到文章后批示,“建议各乡各社普遍照办”,随后提出“妇女能顶半边天”的口号,并迅速进行全国性宣传。(红潮-《建国后“妇女能顶半边天”的口号从何而来?》)这一概念恰好符合当时美国第二次妇女运动浪潮的核心理念,于是“妇女能顶半边天”还引起了西方左翼知识分子的积极反响。(钟雪平-《重新理解“妇女能顶半边天”》)

中国女性的社会地位提高,被认为是争议最少的毛泽东遗产之一(蒙克-《毛泽东遗产争议:妇女能顶半边天》)。1950年,中国通过第一部婚姻法,其中规定“废除包办强迫、男尊女卑、漠视子女利益的封建主义婚姻制度。实行男女婚姻自由、一夫一妻、男女权利平等、保护妇女和子女合法权益的新民主主义婚姻制度。”同时,女性接受教育的权利也得到保障,基础教育系统里的性别差距逐渐减少。

那么,透过这些宏观的历史事件,中国女性的解放运动是如何影响到每个个体的呢?我尝试梳理自己家中三代女性的人生境遇,看是否能从中探知一二。

从最长那一辈开始说起-我的奶奶,经由包办婚姻嫁给她的丈夫,曾参与解放战争,建国后被安排在当地政府某部门工作。由于从未正式受过教育,不识字的奶奶只能放弃这一职位。奶奶不会讲普通话,我只能以粤语方言同她交流。她一生中去过的最远的地方,是广东省的首府广州市;我的外婆,也是通过包办婚姻嫁给她的丈夫,在婚礼之前,甚至从未见过她未来伴侣的模样。建国后,作为四个孩子的母亲,她参加了文化学习班,学会读书认字。她喜欢读报,喜欢看电视上的体育比赛,还喜欢评论我的衣着品味。而幸运的是,她们二人都没经受过缠足之苦。

然后是我的母亲。她在文革十年期间长大,18岁被招收入伍,是当地极少数通过考核的女兵之一。她在空军服役五年,学会了如何修理无线电。退伍后,她被分配到当地图书馆工作,每月负责购置西方文学名著。比起柯南.道尔,她更喜欢阿加莎.克里斯蒂的侦探小说。高考制度恢复后,她参加了成人高考,并顺利通过,得以进入大学学习哲学。她经由大学时的舍友,认识了她现在的丈夫。毕业后她成为了当地政府的一名办公室职员,随后晋升至中层管理级别。她很满意自己的职业生涯,退休后最大的爱好是旅行,前一段时间刚从俄罗斯回来,现在正计划下个月去澳洲和新西兰。

最后是我,代表家中最年轻的一代,从小接受九年制义务教育,少年时代最大的爱好是音乐和电影。高中时期非常迷恋英国独立音乐,曾写过一些乐评投稿至当时喜爱的音乐杂志。18岁那年我独自来到英国念书,所学专业一直和电影相关。在英国生活的这些年,我认识了来自世界各地的朋友,也早已习惯伦敦独有的多元文化生活方式。我曾经尝试学习德语,但没有成功,后来我想通,有英文作为第二语言,暂时也足够了。

就这样,顺着时间线整理我家三代女性的人生境遇,才惊觉在过去一百多年,中国妇女的社会地位经历了如此显著的变迁。即使在后女性主义盛行的二十一世纪,“妇女顶起半边天”的口号早已过时,但不可否认的是,这句名言以及它背后的意识形态,从根本上推进了中国的女性解放运动。即使实现性别平等的道路仍然漫长,但一步一脚印,彼岸总在不远处。

Cassie Lin is a doctoral student at the University of Westminster. She previously worked as an archive assistant at the University of Westminster’s Chinese Poster Collection, now renamed the China Visual Arts Project Archive.

- TV Drama Discourse on Stay-at-home Fathers in China: Super Dad & Super Kids - January 28, 2022

- Freud and China - January 20, 2022

- “Cultural China 2020″—A Different Take on China - January 7, 2022