Written by Liz P. Y. Chee

In my recently-published book Mao’s Bestiary: Medicinal Animals and Modern China (Duke University Press, 2021) I’ve traced an aspect of Chinese medicine and pharmacology that has been surprisingly neglected despite its controversial character, or maybe because of it. Although the book went to press just at the onset of COVID-19, and does not deal directly with zoonotic disease, it helps fill the gap in our knowledge of how and why ‘medicinal animals’ have proliferated in the modern period, arguing that the early Communist period is an overlooked watershed.

My main argument is that while animals (alongside plants and minerals) were accorded medicinal value from ancient times in China, their use expanded and transformed as they became a resource for state medicine in the Mao period. What the book calls faunal medicalisation was a process that, by the current century, would contribute to the endangerment and extinction of animals as far afield as Africa and South America, but had roots in Sino-Soviet relations, The Great Leap Forward, the Cultural Revolution, and other phases of the first few decades of Communist rule. One of its aspects was the institutionalised ‘farming’ of formally wild-caught animals for their parts and tissues, partly to fuel increased overseas exports which survived despite trade embargos. Farming also increased the number of species marketed as medicine. Even for ‘traditional’ medicinal species, the logic of production sometimes meant infusing even more body parts with curative powers. The Tokay Gecko, for example, was first farmed for its re-growable tail, but is today sold as a whole body on a stick. Scientific studies also expanded treatment regimes and delivery methods, and labs worked on substituting the tissue of more common animals for those facing extinction through medicalisation (e.g. water buffalo horn used to replace rhino horn). Faunal medicine made the transition to capitalism under Deng’s reforms, when bear bile farming – a technology likely pioneered in North Korea – becoming the signature and most controversial of all faunal drug industries.

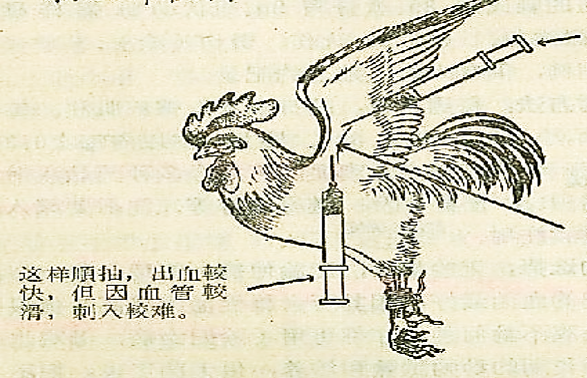

Mao’s Bestiary also provides background on the broader but equally-neglected field of drug-making and discovery in the PRC, which encompassed flora as well as fauna. This included the absorption of famous older brands like Tongrentang into the Communist pharmacy, and the training of a new class of pharmacists and pharmaceutical researchers who would straddle the line between the traditional and biomedical. Soviet pharmacology would also serve to validate and help expand Chinese use of animal (and herbal) medicines, starting with cross-border deer farming, but extending to the export of Russian ‘tissue therapy’ and a wider shared interest in hormonal and blood therapies largely outside the realm of Western biomedicine. Modern Soviet medical theories mixed with references from classical Chinese texts would help spur the signature animal drug innovation of the Cultural Revolution, Chicken Blood Therapy, which forms one of the book’s case studies. While Chicken Blood Therapy is remembered today as a unique eccentricity, motivated by political zealotry, the book contextualises it as one of many examples of hybrid faunal therapies of the late Cultural Revolution, using toads, geese, insects, and other types of animals wild and domestic. Their inventors’ claims that animal tissue could act as powerfully as antibiotics and other Western drugs, even curing cancer and other diseases testing the limits of biomedicine, would help set the stage for the many exalted curative claims of the present day which drive the illegal and legal wildlife trades.

This book grew out of a trip I made to a bear farm on the Chinese-Laotian border in 2009, a story I relate in the Introduction. The spectacle of sick bears being rendered into medicine, which in turn becomes commodified as gifts, led me on a journey to Chinese archives and into the company of Chinese physicians and drug manufacturers willing to discuss issues they know to be controversial even in the past tense. As a Chinese Singaporean I am both a life-long user of Chinese herbal medicine and the inhabitant of one of the world’s great rain forests, whose biodiversity is eroding as fast as that of twentieth-century China. While the continued medicalisation of animals is only one of many causes of the defaunation of Southeast Asia (which is occurring more rapidly than deforestation), historians and anthropologist studying Chinese and other indigenous medicines can no longer turn a blind eye to the ecological and material effects of practices that intrigue them theoretically, especially as they evolve into what Laurent Pordie and Anita Hardon (2015) have called ‘Asian Industrial Medicines’, with strong ties to states, pharmaceutical manufacturers, trans-national trade networks, and in the case of wildlife, criminal gangs and zoonoses. My book is not a history of this time, but one that I hope will clarify and de-mystify, and in some sense de-sanctify practices too easily sold as ‘traditional’ and ahistorical.

Liz P.Y. Chee is a Research Fellow in the STS Cluster of the Asia Research Institute (ARI) and a Fellow of Tembusu College, both at the National University of Singapore (NUS). She was the first graduate of the University of Edinburgh – NUS Joint PhD Program, and completed her dissertation under the supervision of Prof. Francesca Bray. She has an undergraduate degree in Japanese Studies and an M.A. in East Asian History, and briefly worked for the Singapore bureau of the Asahi Shimbun newspaper before returning to academe. She completed most of the research for this book at the Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine. Image caption reads ‘Chicken Blood Therapy as introduced to the Chinese population during the Cultural Revolution.’ Source: Qinghai Sheng Ba Yi Ba Youdian Zaofan Tuan Bianyin, Jixue Liaofa (1967).

- TV Drama Discourse on Stay-at-home Fathers in China: Super Dad & Super Kids - January 28, 2022

- Freud and China - January 20, 2022

- “Cultural China 2020″—A Different Take on China - January 7, 2022

[…] opening piece, written by Liz P. Y. Chee, discusses faunal medicalisation in modern China. Chee traced the relatively neglected topic of […]