By Sheng Zou

As nationalist sentiment climaxed in Mainland China in the wake of the Hong Kong protests and amid the celebrations of the 70th anniversary of the founding of the PRC, new life has been breathed into a number of classical propagandistic songs, or “red songs,” which were both broadcast and performed en masse across the country. One of the revitalized songs is “My People, My Country,” a propaganda anthem from 1985 that has recently been covered by Chinese pop diva Faye Wong with a new musical arrangement for a hit Chinese movie of the same name. The song is included in the catalog of a hundred red songs released by the Department of Publicity to celebrate the anniversary.

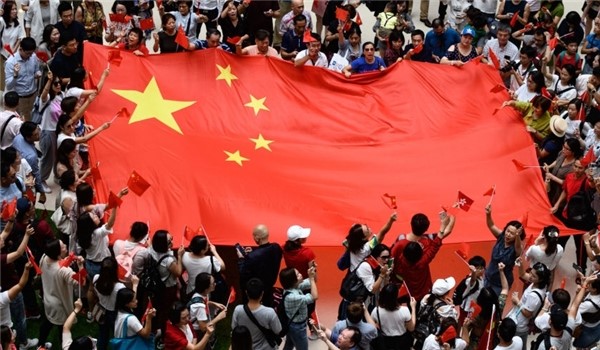

The revival of classical red songs has taken a participatory and performative turn, as patriotic singing competitions and choral flash mobs spread across Chinese communities at home and abroad. In August, patriotic Chinese students around the world took to the streets, waving national flags while singing together to defend and honor their homeland. In September, pro-Beijing demonstrators in Hong Kong gathered in malls to sing China’s national anthem and classical red songs such as “Ode to the Motherland,” which constituted a counter-voice to “Glory to Hong Kong,” an anthem adopted by Hong Kong protesters to foster internal solidarity. Meanwhile, organizations and communities across China, large and small, held singing competitions where citizens performed patriotic songs live.

Pro-democracy protestors in Hong Kong singing the song “Glory to Hong Kong” Image credit: Studio Indendo

This fervent wave of choral flash mobs and singing competitions constitutes a re-emerging sonic infrastructure grounded in local and identity-based communities where music is circulated and practiced in the service of national cohesion. Over the past decades, from loudspeakers and radios, to tapes and CDs, and further to digital devices and apps, practices of music making and listening have been radically decentralized and personalized; yet these recent flash mobs signify a return of the collective in people’s everyday experience with music. In the following, I will discuss how music could be deployed to consolidate national identification; how choral flash mobs allow for a kind of sonic and bodily bonding (Turino, 2008; McNeil, 1995) due to their distinctive participatory and performative properties; and how these flash mob performances relate to cultural/national identity formation.

Much attention is paid to the ways music is deployed as a means of political resistance, such as the iconic protest song “March for the Beloved,” which, since South Korea’s Gwangju Democratization Movement, has inspired other social movements in Asia. Nonetheless, music can also be harnessed as a medium of political and ideological control. In China, political and ideological control via music is achieved through appeals to people’s nationalist sentiment and identity. Since late 1970s, patriotic red songs, sung by a few professional singers employed by state troupes, often featured metaphoric terms such as “home”/“homeland” (Baranovitch, 2003), in order to blur the line between political nationalism and cultural nationalism, or to transfer people’s love for the nation to the Party-state. However, with the market-oriented reforms in China’s media and cultural scenes and the influx of foreign music genres, many of these red songs gradually lost their grip on people, especially younger generations. On the one hand, other music genres, such as hip-hop, have been incorporated into propaganda campaigns (Zou, 2019). On the other hand, attempts have been made to revitalize the red songs through new renditions and covers.

The power of music in evoking nationalistic tendencies should be analyzed in terms of both its sonic and symbolic qualities. Music is often seen as a vehicle for lyrics, but as Revill (2000: 602) observes, the “physical properties of sound, pitch, rhythm, timbre” work on and through the body, granting music “a singular power to play on the emotions, to arouse and subdue, animate and pacify.” Therefore, the sonic, rhythmic, and melodic qualities of music that give rise to particular sensory, somatic, and mental experiences should be examined in their own right. In this sense, the ideological power of patriotic red songs stems largely from their rhythmic and melodic qualities that induce particular emotional orientations, such as solidarity, solemnness, or conviviality.

The symbolic quality of music—realized through meaningful lyrics or associated memories and tropes—constitutes another major source of musical power. Music is made at a particular time in a concrete place; its specific temporal and spatial dimensions allow it to carry memories and mark spatial boundaries. Bohlman (2004), for instance, argues that nationalistic music not only contributes to ethnic consciousness, but also serves nation-states in their struggle over contested territory. Likewise, red songs such as “My People, My Country” and “Ode to the Motherland” not only give people access to a symbolic past, but also invoke “cultural geographies of exclusion and inclusion”(Revill, 2000: 598). Such terms as “people”, “country” and “motherland” have definitional boundaries that demarcate the in-group from the out-group, reinforcing a sense of national sovereignty and integrity.

Memories, however, are not just “transmitted” by these songs to new generations; they are also reconstructed, reformulated and re-inserted into contemporary structures of feeling. The symbolic open-endedness of these patriotic songs makes this reformulation possible. Faye Wang’s cover of “My People, My Country” manifests another technique to re-insert memories of the past into the fabrics of contemporary life in ways legible to the contemporary audience.

The choral flash mobs as an embodied sonic infrastructure further contribute to the consolidation of national identification. Different from the top-down Red Culture campaign operative from 2008 and 2012 in Chongqing, the latest wave of patriotic flash mobs appears to be spontaneous and self-organized. The participants, as both singers and listeners, gather together to make collective sound, live. The liveness of flash mob performances—manifested in the acts of singing, cheering, or moving together in synchrony—has the potential to create “strong emotional links between the individual and the group” (Eyerman, 2002: 450). Group singing as a participatory and performative ritual leads to a sense of unity and intersubjective connection, similar to what Victor Turner (1991: 96) calls “communitas,” namely a state of “homogeneity and comeradeship” among individuals in rituals. In the context of nation-states, Benedict Anderson (2006:145) observes that people singing national anthems on national holidays share an experience of simultaneity that he characterizes as “unisonance”—a sonic and embodied experience of an imagined community.

In these choral flash mobs, people also have a similar embodied experience of simultaneity as they sing the same verse to the same melody. During a flash mob taking place at a shopping mall in Hong Kong on September 12, pro-Beijing demonstrators sang the “Ode to the Motherland” in unison, while facing toward a large national flag hanging from the second floor. Many of them were also waving small national flags while singing. In much the same way individual voices converged into one, the individuals merged into a homogeneous group where particularities were temporarily cast aside. Choral flash mobs provide an occasion for “sonic bonding” (Turino, 2008), where people make collective sound, move in synchrony, and experience a sense of togetherness. Participants perform not only music, but also their devotion to the nation-state, when their sense of national identity and pride is challenged by the ideological and discursive battles of the latest geopolitical crisis. Characterized by liveness, embodiment, participation, and performance, choral flash mobs enable a spectacular and aesthetic representation of national identity, where top-down ideological governance coalesces with bottom-up nationalist sentiment.

Sheng Zou is a Ph.D. Candidate in Communication at Stanford University, and a Geballe Dissertation Prize Fellow at the Stanford Humanities Center. His research interests include media globalization, new media and society, politics and popular culture, digital economy and labor, with a particular focus on contemporary China. His research has appeared or is forthcoming in various journals including Global Media and Communication, Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies, Journalism, Journalism Practice, Digital Journalism, TripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique, and Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture. Image credit: AFP

- TV Drama Discourse on Stay-at-home Fathers in China: Super Dad & Super Kids - January 28, 2022

- Freud and China - January 20, 2022

- “Cultural China 2020″—A Different Take on China - January 7, 2022

[…] the first piece, Sheng Zou discusses the ways in which music is often deployed to consolidate national identification. […]