Written by Shih-Wen Sue Chen

Children’s writers mediated a complex textual discourse on China for young readers in the Victorian and Edwardian period, trying to make ‘knowledge’ of ‘the Celestial Kingdom’ accessible to the British public after China was ‘opened up’ to the West after losing the Opium Wars. A plurality of viewpoints on China is evident in the numerous books for children that were produced in the years between the Opium Wars and the First World War. Here, I provide a glimpse into the rich texture and scope of British representations of ‘China and the Chinese’ in children’s texts published in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries.

The British children’s book market changed as literacy rates rose after the passing of Forster’s Education Act in 1870. The Act allowed for the establishment of board schools and authorized school boards to make attendance compulsory. By 1880, there were over one million new places in schools set up. Observing this phenomenon, publishers took the opportunity to market various forms of literature to the children of the British Empire.

Sunday School Texts

The editor and author J. A. Hammerton (1871-1949) remembered being excited about ‘a beautiful colour-book on Chinese life’ given to him by his great-aunt for Christmas. For those children whose families could not afford books like the ones Hammerton received, Sunday schools provided a repository of discourses on China. Children may have pulled books such as Peeps into China, The Children of China, The Chinese Boy and Girl, and The Land of the Pigtail off the shelves of Sunday school libraries, or received them as rewards. Some Chinese Waifs and The Boy with a Borrowed Name were among the various Sunday school leaflets published by religious organizations such as the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge and the Religious Tract Society. These Sunday school texts were often used to encourage children to raise money for missions. While many of these missionary texts reinforced the image of the Chinese as ‘Other’, some authors emphasized the similarities between British and Chinese children to point out the universal need for Christianity, as I have explored. By taking part in religious plays and cantatas such as Queen Lexa’s Chinese Meeting: A Missionary Recitation for Eight Girls and Three Boys, Busy Bees: A Missionary Dialogue in Three Scenes, and Missionary Cantata: Every-day Life in China, children were exposed to representations of Chinese children, particularly girls, as pitiful, helpless innocents suffering at the hands of adults who forced their daughters to be foot-bound and gave their children ‘very strange’ names, as I have examined.

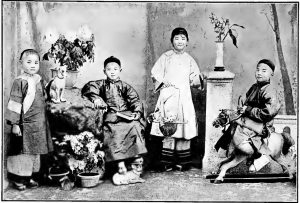

Image from Isaac Taylor Headland’s The Chinese Boy and Girl (1901). Source: Wikimedia Commons

Children’s Periodicals

Children interested in China could satisfy their curiosity by reading the wide range of magazines that flourished in the late nineteenth century. For example, the CMS Juvenile Instructor and Juvenile Missionary Magazine frequently carried articles on China, with titles ranging from ‘Chinese Children’ to ‘A Chinese Funeral’. Young readers could also gain information from the Religious Tract Society’s numerous periodicals, such as the Child’s Companion and Juvenile Instructor, Child’s Paper, The Girl’s Own Paper, and The Boy’s Own Paper.

Stereotypical images of ‘the Chinese’ circulated in The Boy’s Own Paper (1879-1967), one of the most popular children’s magazines in the Victorian era. Chinese people were considered distinctly different physically, with their ubiquitous queue, slanted eyes, and buck-teeth; psychologically, they were believed to be devious, cruel, and evil. One telling visual example of this stereotype can be found in vol. 28 of The Boy’s Own Paper. On page 312, there is an engraving by Leo Cheney inserted into the space between the end of one story and the beginning of another. The words ‘The End’ appear above the illustration. These words could either be used to signify the closure of the previous story, or be interpreted as the image caption. The engraving features the profile of a skinny Chinese man with an elongated neck and a big head standing in front of a table preparing to kill an innocent-looking puppy. With one hand, he lifts up the puppy by its neck, in the other, he holds a large scythe-like knife. Underneath his cap, a very long pigtail, adorned at the end with a ribbon, flows down his back, reaching past his knees. His narrow, slanted eyes appear even smaller in contrast to his big smile, which might suggest that he has been starving for so long that he, the stereotypical dog-and-cat-eating Chinese, is very eager to devour the dog. The adorable fat puppy stares pitifully at the readers, reminding them of their own pets and making them shudder at what will inevitably take place. While racial caricatures were present in numerous children’s texts published in Britain when it was at its height of imperial power, my research has shown that diverse images of China and the Chinese appeared in children’s travelogue storybooks, historical novels, adventures stories, and periodicals published in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries.

Adventure Stories, Historical Novels, and Detective Fiction

Edwin Harcourt Burrage’s Ching-Ching series provides a counterpoint to the image of the dog-killer described above. Ching-Ching first appeared in a story serialized in The Boy’s Standard (1875-92), and later featured in his own magazine called Ching Ching’s Own (1888-93). On the surface, Ching-Ching seems to be a stereotypical Chinese comic relief character who speaks Pidgin English and sports pigtails. However, child readers loved his character so much that the author decided to transform Ching-Ching from a minor side-kick into a detective hero who solves cases in England. In the early twentieth century, another ‘great Chinese detective’ entertained child readers: Charles Gilson’s Mr. Wang.

|

|

| Cover of Among Hostile Hordes. Source: author. | Cover of With the Allies to Pekin. Source: Internet Archive |

Mr. Wang is a key character in at least nine stories, including The Lost Column (1909), which is set during the Boxer Uprising (1899-1901). Adventure novels such as The Lost Column, Bessie Marchant’s Among Hostile Hordes: A Story of the Tai-ping Rebellion (1901) and G.A. Henty’s With the Allies to Pekin (1903) underscore the historically complex relationships between Britain and China. Boxer narratives for children published between 1900 and 1909 provided different interpretations of the same event. As I have argued, the Boxer Uprising was a pivotal conflict from which negative images of the Chinese and fears of the Yellow Peril emanated. It is therefore important to consider the state of Sino-British relations during the text’s production because they influenced how ‘China and the Chinese’ were represented in children’s literature.

Dr Shih-Wen Sue Chen is Senior Lecturer in Writing and Literature at Deakin University. She received her PhD in Literature, Screen and Theatre Studies from the Australian National University. Her research focuses on British and Chinese children’s literature and culture from the mid-nineteenth century to the present. She is the author of Children’s Literature and Transnational Knowledge in Modern China: Education, Religion, and Childhood (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019) and Representations of China in British Children’s Fiction, 1851-1911 (Routledge, 2013).

- TV Drama Discourse on Stay-at-home Fathers in China: Super Dad & Super Kids - January 28, 2022

- Freud and China - January 20, 2022

- “Cultural China 2020″—A Different Take on China - January 7, 2022

[…] our first piece, Shih-Wen Sue Chen discusses the rich texture and scope of British representations of ‘China and the Chinese’ in […]