Written by Tessa Thorniley

The publication of the literary journal, The Penguin New Writing (TPNW), spanned a traumatic period of history including WWII and its aftermath, and in China, the Second Sino-Japanese War. It was a period when representations of China in Britain shifted as sympathy for the plight of the Chinese people increased, particularly after Britain and America declared war against Japan at the end of 1941. This shift was reflected in the literature about the country and its people published in Britain at that time, most noticeably in newspapers, magazines, journals and in the output of publishers with Leftist and/or pro-Communist political sympathies which viewed Japanese occupation as an act of fascist aggression.

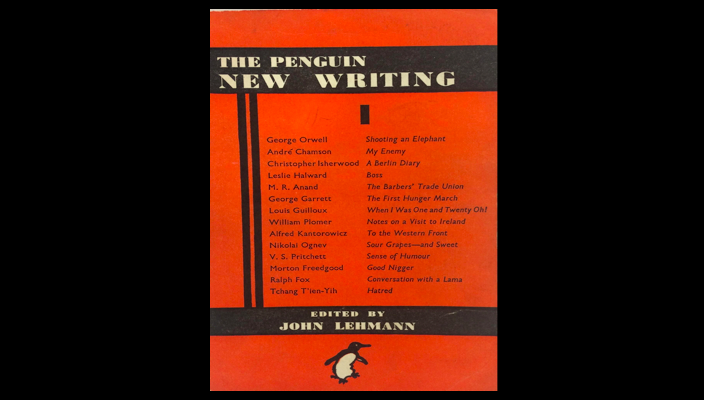

After securing the backing of Penguin Book’s co-founder Allen Lane, TPNW, soon became one of (if not the) most successful literary magazines published in Britain during WWII. Alongside the British and Chinese writers whose short fiction and literary criticism about China is briefly introduced here, the journal published original fiction, reportage, poetry and criticism by: George Orwell, Elizabeth Bowen, Stephen Spender, Christopher Isherwood, V.S Pritchett, W.H Auden and Cecil Day-Lewis among others.

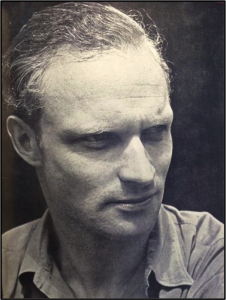

At the helm was the autocratic editor, John Lehmann, who is probably better known for his 1930s New Writing periodical (of which TPNW was a successful offshoot) and as co-owner of Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s Hogarth Press. Lehmann’s contribution to the promotion of international writers has received scant critical attention, even though the magazine’s circulation – which reached 100,000 shortly after the war – points to an extremely wide readership for a literary magazine and around a third of the contributors (to Lehmann’s New Writing venture in its entirety from 1936-1950) were non-British. As well as literature from and about China, TPNW featured paintings by official British war artists who travelled to Hong Kong and Burma, but here I will focus on ten stories.

John Lehmann

Access to modern Chinese literature in the 1930s and early 1940s Britain was limited. While publications such as Life & Letters Today, The New Statesman & Nation, and Left Review published short stories and poetry by Chinese writers, there were few serious literary editors inclined to or capable of seeking it out. And while Lehmann’s pro-Communist affiliations had steered his initial interest in and sympathy towards China, he required a wider network of translators and experts – which came to include the Sinophile Harold Acton and the Chinese writer Xiao Qian (Hsiao Ch’ien) – before he would consider publishing works in Chinese translation.

One of Lehmann’s early collaborators was Ralph Fox, the British Communist whose contribution in the first issue of TPNW (1940) was published posthumously after his death in the Spanish Civil War. Fox’s story, set in Mongolia where he had travelled, is a dialogue between a narrator and a lama or holy man in which they muse, over tea and airik, on Russian and Chinese influence in the region. Fox’s tale is an exploration of the potential for deeper understanding between East and West, and it sets the tone for ideas relating to China (and indeed Russia) in the journal.

In the same issue, Lehmann published a short story by the Chinese writer Zhang Tianyi (Tchang T’ien-Yih) whose longer fiction is still being translated today (Zhang Tianyi (tr. David Hull), “The Pidgin Warrior” (Balestier Press, 2017), a grim and powerful account of the suffering of Chinese civilians and soldiers during the period of early Japanese occupation in the north of China and civil war. In his memoirs, Lehmann wrote of the ‘brotherhood of oppression’ which united contributions to his magazines from around the world, Zhang’s story being a particularly striking example of this spirit of writing.

Lehmann’s most significant and fruitful link with China came through his close friendship with Julian Bell (son of artists Clive and Vanessa Bell and nephew of Virgina Woolf) who briefly taught English at Wuhan University. In correspondence, Bell introduced his best pupil, Chun-chan Yeh (Ye Junjian), to Lehmann and they struck up a friendship that lasted for several decades, long after Bell was killed fighting in Spain. In 1939, Ye sent Lehmann a manuscript of the translations of 20 wartime short stories by Chinese writers which he had worked on while engaged in semi-official propaganda work in Hong Kong.

Ye Junjian (Chun-chan Yeh) with permission from his son.

The manuscript was never published whole but Lehmann selected several stories from it which he felt would resonate with his Anglophone readers. These included short fiction by Yao Xueyin (Yao Hsueh-yin), Bai Pingjie (Pai Ping-chei), S.M (a pseudonym for Ah Long or Chen Shoumei) and a second story by Zhang. All had been written during a period of relative optimism in the war against Japan, when China was unified under the Second United Front.

The underlying narrative theme in these works is the shifting consciousness of the Chinese people, particularly the peasantry who are seen taking up arms against a common enemy in rural areas as guerilla fighters. The stories suggest a populace that is awakening, and seeking to overcome its shortcomings, to play its part in the war. A sharp satire by Zhang (his second short story in TPNW) takes a swipe at the ineptitude and moral corruption of certain types of Nationalist government officials. While there is a strong underlying leftist agenda to the stories, for Lehmann, any propaganda value had to be outweighed by literary qualities.

The need for representations which brought the people of China to life in the West had been highlighted by the American journalist and writer, Emily Hahn, in 1937 when she pleaded for her Anglophone readers to see China as ‘a living sister’ rather than a ‘dead ancestor’. Xiao Qian similarly criticised those who viewed China as a ‘heap of bones and stones’. Using satire, humour and sharp dialogue, the stories in TPNW conveyed the country’s unity and the dynamism of its people and by doing so they also pushed against Western archetypes of Chinese soldiers as inept, badly led and ineffective, of officials as inhumane and of the people as passive or backward.

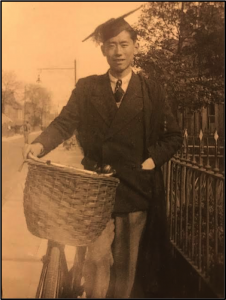

From the end of the war Lehmann published short stories by Chinese writers living in Britain and writing in English, including by that time, Ye, but also Kenneth Lo (best known today as author of 40 Chinese cookery books and the restaurateur behind Memories of China). Lo’s tale in TPNW 24 (July 1945) was a short story based on the extraordinary real life account of the Chinese seaman Poon Lim who had become a global celebrity after he survived for what was then a record 133 days adrift on a raft in the South Atlantic Ocean. In Lo’s story, Lim is described as orderly, physically and psychologically capable, calm and rational and as an individual whose Chinese upbringing had equipped him to endure what few others had ever managed. This representation of Lim ran very much counter to press reports of marauding Chinese seamen, commonly found in newspaper reports around the time. As a Chinese liaison for Chinese seamen based in Liverpool during the war, Lo had been a position to observe and document their lives and was keenly aware of the prejudices and injustices they suffered while serving on British merchant ships.

Kenneth Lo, Cambridge 1936 – 1941 (with permission from his family).

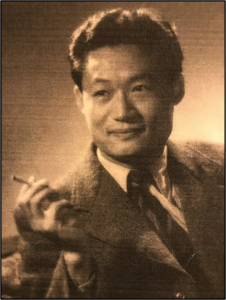

Ye travelled to Britain in 1944 at the behest of the British Ministry of Information to raise morale ahead of the Normandy landings with tales of Chinese resistance. During the time he spent in Britain, until 1949, Lehmann supported and promoted Ye’s writing career and welcomed him into his literary network. When Ye came to publish his own short stories and his first novel in English they received glowing reviews in the literary press. His two short stories published in TPNW after the war reflect on the tension between traditional and modern China and the brutality of the old ways.

By publishing works of modern Chinese literature by unknown Chinese writers alongside established British, European, and Russian writers, Lehmann sought to elevate modern Chinese literature for his Anglophone readers around the world. His archived correspondence from this period in Austin, Texas, is explicit about his intention to elicit sympathy for China’s cause by publishing the work of living Chinese writers. His efforts attracted the attention of George Orwell, then at the BBC’s Eastern Service, who ran a series of broadcasts about China’s modern literature after reading stories in Lehmann’s journals. Acton, was among those in Lehmann’s China network who shared his enthusiasm for China’s contemporary literature and in an article about literary developments in the country for TPNW 15 (1943), Acton highlighted its innovative qualities.

This period was the first time in Britain that a body of Chinese writers represented themselves and their country. The trajectory of Ye’s (and several other Chinese writers’) literary careers, is suggestive of an openness towards and interest in more nuanced representations of China in Britain. Lehmann, TPNW and his Chinese network had a fascinating role to play in these unofficial Sino-British relations where sympathetic representations of China briefly flourished prior to 1949.

Tessa Thorniley recently completed her doctoral thesis at Westminster University about the Chinese writers published in The Penguin New Writing. She has contributed a chapter about the wartime short stories of TPNW for a forthcoming collection for Edinburgh University Press and is contributing to an edited collection about the Chinese writer and illustrator Chiang Yee (who was recently awarded a blue plaque in Oxford, Blue plaque for the Chinese travel writer who won the heart of 1930s Britain). She has taught contemporary Chinese literature and society at Westminster University. Prior to doctoral studies she spent seven years living and working as a freelance journalist in Shanghai and Beijing.

- TV Drama Discourse on Stay-at-home Fathers in China: Super Dad & Super Kids - January 28, 2022

- Freud and China - January 20, 2022

- “Cultural China 2020″—A Different Take on China - January 7, 2022