Written by Adam Liebman

Four garbage bins for four categories of waste: wet, hazardous, recyclable, and dry. In 2019, news stories about Shanghai residents being forced to sort and deposit their household waste according to these categories rippled through the international news media. The rules included limited times for dropping off waste and confusing categorical requirements, leading to complaints of inconveniences, unfair penalties, and state overreach. This effort to improve waste separation in urban China was rolled out in 46 pilot cities in 2020, including Kunming, where I engaged in waste fieldwork on and off throughout the 2010s.

Garbage bins function as a crucial nexus that connects the state with two different social groupings. On one side are relatively well-off urbanites who generate and deposit most post-consumer waste (the main focus of media coverage); while on the other side are large populations of waste workers, both formal and informal, who make a living through handling these wastes (mostly missing from media coverage). As such, looking at changing bin designs, aesthetics, and the politics of their placement provides a lens into shifting urban political ecologies in contemporary China. Below is a brief history of garbage containment efforts in Kunming that includes both social groupings to help contextualize the recent initiative.

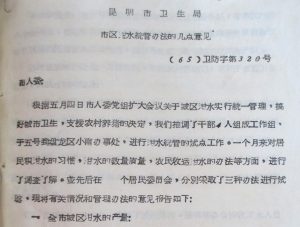

1965. The frenetic scrap collection campaigns of the Great Leap Forward had passed, but an ethos of thrift and material reuse was still widely promoted for its potential to help the nation industrialize. In this context, the Kunming sanitation bureau set out to unify regulation of the city’s system of collecting food waste and distributing it to villages outside of the city for use as pig feed or fertilizer. The bureau drafted a report for the city’s leaders comparing three methods: either setting up a costly system of workers, facilities, and vehicles to collect and transport the waste; allowing peasants to continue entering the city to pick up waste collected by urban workers; or continuing to allow peasants to collect food waste directly from residential areas, cafeterias, and restaurants, while adding some new restrictions.

Fig 1. The beginning of a long report on improving the regulation of food waste collection, copied from the Kunming City archives by the author.

In the last method, the most economical, three ‘drawbacks’ listed are especially revealing:

- Peasants going to people’s courtyards to collect food waste is a fragmented process, which takes more time and wastes labour power

- The times when peasants enter and leave the city cannot be guaranteed, influencing urban aesthetics and appearances

- When peasants themselves go to courtyards to collect, usually they will not seriously clean the buckets and containers, influencing the environment and hygiene.

The cleanliness of ‘buckets and containers’ for collecting food waste (precursors of black-box garbage bins) thus appears to be a larger concern than are peasants who appear reduced to their only use: labour power. Peasants are seen to be as potentially polluting in the city as rotting food waste, and the report makes it clear that the state’s efforts to systematize waste collection are often tied to projects of containing devalued people as well as matter.

1978. Deng Xiaoping had taken over leadership of the communist party in the wake of Mao’s death, markets had emerged for selling surplus agricultural products, and many Kunmingers were enjoying a new abundance of fruits and vegetables. But with this small shift from scarcity to abundance came a proliferation of stinking garbage, straining Mao era systems of collection and reuse. A report from this year hints how this process played out. To improve ‘urban aesthetics and sanitation’, the sanitation bureau constructed 216 new garbage repositories in which waste could be deposited and partially contained before being transferred to larger garbage dumps. However, twelve of these new repositories had been demolished by work units and neighbourhood associations that were seeking to expand their businesses. One repository was replaced with a business selling cold drinks, another with a restaurant selling rice noodles (a Yunnan specialty). Clearly, some work units had been quick to take advantage of new economic opportunities, and they were not allowing the city’s new waste infrastructure to impede them.

Without these repositories some city residents were left without a designated place for disposing garbage and had to merely leave it nearby. This not only influenced the city’s appearance. More seriously, it blocked roadways, prevented garbage trucks from getting through, generated a rotting stench, and ‘raised the ire of the masses’. The sanitation bureau required offending work units to reconstruct the repositories. In this way, the responsibility of the local state can be seen shifting from overseeing the conversion of waste to value while containing the dirt and stenches of devalued things and people, to a fuller battle with merely attaining elusive containment.

1998. The city began to install in public spaces garbage bins containing two separate sides: one for ‘recyclable waste’ and the other for ‘non-recyclable waste’. The new bins were part of the city’s efforts to not only appear more modern and hygienic, but also more ‘green’ and ‘ecological’ as it prepared to host the World Horticulture Exposition the following year. Yet, both sides of the new bins soon came to be used for all waste as urbanites noticed that both sides were dumped back together into the same vehicles, making clear the state’s lack of an actual recycling system. Practices that functioned to ‘recycle’ waste were still widespread, but increasingly occurred through waste workers and garbage pickers pulling out wastes of value to sell to informal scrap traders, as well as through lower income urban inhabitants habitually saving and selling their scrap in ways that avoided the state’s bins altogether.

2011. While beginning fieldwork for this project, I encountered a particularly interesting manifestation of the pairing of ecology and modernity: a hefty, bright green garbage bin, with posters on three sides showing utopian green cityscapes underneath fluffy white clouds, floating bubbles, and a mix of English (‘Environmental protection’), pinyin (Sheng Tai Huan Bao), and Chinese characters (生态昆明,绿色昆明,园林昆明). As I got closer to the can, its plexiglass screens retracted and a mechanized female voice loudly and repeatedly instructed me to ‘protect the environment, take care of hygiene’ (保护环境,爱护卫生 baohu huanjing, aihu weisheng).

Fig 2. Smart garbage cans in Kunming’s Cuihu Park. Source: author.

Later I found a news article that reported on the project: ‘48 Smart Garbage Cans Enter Cuihu [Park]’. Of course, smart-cans! After all, this was an era when teens sold kidneys to acquire iPhones and other coveted digital devices. Smartness was an emergent idiom of the time, indexing modernity, innovation, and global connectedness. Yet, the stated goals of the smart-can pilot project were more modest: handling growing quantities of waste; preventing the wind from blowing garbage out; containing foul odours; providing space for public service advertisements; and providing light at night so the cans and messages can still be seen. Access to the contents of the bins was restricted by locks, making it almost impossible for the large numbers of garbage pickers active in the park to identify and pull out items that could be sold as scrap. Thus, while the cans’ affects were designed to help produce ecologically conscious, modern waste disposers, the project also was enclosing one of the most important material means enabling the urban poor to eke out a living in the city.

2021. When journalists and scholars turn their focus to new approaches to garbage sorting and containment, they would be wise to consider two important questions highlighted in this history. First, how are both the formal and informal infrastructures used to process waste changing in connection with new containment regimes, if at all? And second, how is the approach shifting waste workers’ burdens of handling valueless waste while also shifting others access to wastes of value?

Adam Liebman is an assistant professor of anthropology at DePauw University. He is currently working on a book monograph called Recycling Uncontained which explores waste circulations and containment struggles in and beyond Kunming. His published articles include Waste Politics in Asia and Global Repercussions (2021) and Reconfiguring Chinese Natures: Frugality and Waste Reutilization in Mao Era Urban China (2019). Featured image from CGTN.

- TV Drama Discourse on Stay-at-home Fathers in China: Super Dad & Super Kids - January 28, 2022

- Freud and China - January 20, 2022

- “Cultural China 2020″—A Different Take on China - January 7, 2022

[…] in Asia and Global Repercussions” in the spring issue of the journal Education About Asia and “Garbage bins are for containing people too” on the Contemporary China Centre […]

[…] the third piece, Adam Liebman examines how changing garbage bin designs, aesthetics, and the politics of their placement provide […]

Garbage bins function as a crucial nexus that connects the state with two different social groupings. it is very helpful to clean your living area. i advised everybody to use them. your blog looks impressive keep continue to share more blogs. Thanks for the nice information .