By Dr. Jamie Furlong, Research Fellow, ATA

The ReVeAL project (Regulating Vehicle Access for Improved Liveability) organised its Final Conference on 8-9 November in London. The aim of the project – running since 2019 – has been for multiple cities across Europe to successfully implement ‘smarter Urban Vehicle Access Regulations’, otherwise known as UVARs. UVARs include Low Emission Zones (LEZs), parking regulations, congestion charging schemes, Limited Traffic Zones (LTZs), cycle lanes and pedestrian zones. The project has, according to its own description, sought to “enable cities to optimize urban space and transport network usage through new and integrated packages of urban vehicle access policies and technologies for the benefit of people living in these cities, in order to reduce emissions and noise, and increase accessibility and quality of life”[1].

Cities that participated in the project were diverse: Jerusalem (Israel), City of London (UK), Padova (Italy), Vitoria-Gasteiz (Spain), Helmond (Netherland) and Bielefeld (Germany). The final conference was a space for representatives from each of the participating cities to show what they had implemented, demonstrate the outcomes of the project, and discuss some of the key challenges they faced in implementing UVARs. Some of the key themes that emerged from these discussions are outlined below.

The importance of context

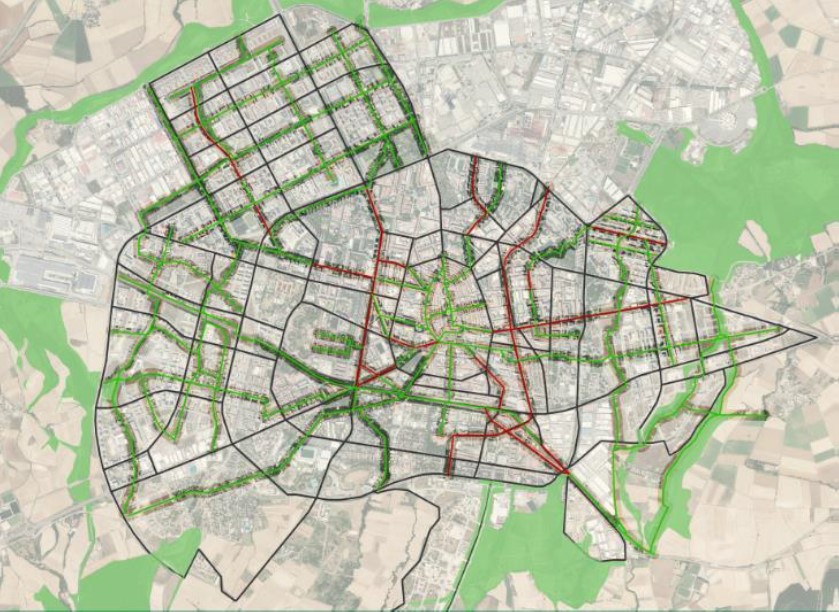

Each city has its own unique context. In the City of London – an area of just 1 square mile, 90% of people who come into the area walk at least some of that journey. Yet the public allocation of space did not reflect this – the project aimed to reallocate space through the creation of wider pavements, bus gates and parklets. In contrast, Padova city centre is a UNESCO World Heritage site with a high concentration of commercial and food/beverage activities. In this more densely populated context, Padova implemented a ‘superblock’ (“SuperGuizza”) – much like those made famous in Barcelona – which has had some success in reducing the volume and speed of motorised through-traffic in the area. The context in Vitoria-Gasteiz is somewhat similar – an ultra-dense conurbation in which 98% of the population live within 3km of the city centre. In Vitoria-Gasteiz, the aim was to create more liveable public space. Through the creation of superblocks with a more tactical urbanist slant, they aimed not to change the type of cars entering spaces of the city through low emission zones, but to put pedestrians first. The long-term aim being that the whole city will be separated into superblocks that restrict through traffic and have more liveable streets. This was a hugely impressive demonstration of the progress made in Vitoria-Gasteiz and is reflective of the changes made in many Spanish cities, from the superblocks in Barcelona to the complete reallocation of space for pedestrians in Pontevedra.

The key here is that we cannot ‘universalise’ approaches from one place to another. Whereas in Vitoria-Gasteiz, the project began with a very clear superblock concept, in Bielefeld, they began with a completely blank slate about what was possible. Even the aims were quite different: in Bielefeld, where 51% of trips are taken by car, a key priority was acquiring strong support from stakeholders and convincing the public of the benefits of creating a more pedestrian-friendly old town that can be scaled-up in the future. Perhaps the biggest contrast comes between the contexts of Helmond in the Netherlands and Jerusalem, Israel. In Helmond, as part of the project they planned and constructed a zero-emissions district – a largely residential area where motorised cars cannot enter, with an aim of 0.2 parking spaces per household. Such a radical approach is perhaps a little more achievable when, rather than transforming existing space, you are creating an entirely new space in a country where prioritising non-motorised transport is well-established in public policy. In Jerusalem, Nimrod Levy explained that they were beginning from a very different context: their extension of the low emissions zone from the pilot city centre area to cover the whole city was only the second major piece of work in Jerusalem aimed at cutting transport emissions.

Public awareness and engagement

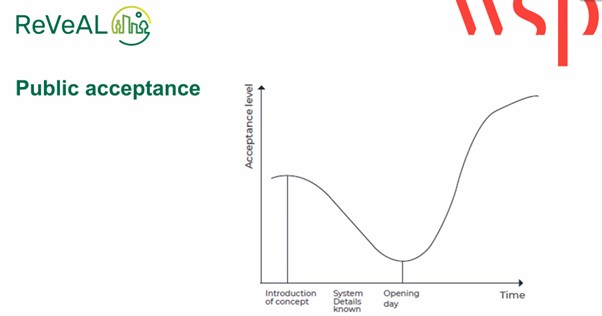

Another key theme that emerged across all the projects was the importance of public awareness and public/stakeholder engagement. Julie Shack, a transport planner from WSP, emphasised that how a UVAR is communicated will significantly affect how it is perceived by the public. Typically, as shown by the graph below, public acceptance of schemes restricting vehicle access go through different phases, from open-mindedness at the start, to a more negative response when the change is implemented and has an impact on motorised mobility, to a longer process of becoming accustomed, perceiving the benefits and wider acceptance.

Some of the key success factors to achieving this wider acceptance are being able to sell the advantages, using the right language, providing the right amount of information at the right time and using the right channels of communication to target specific audiences. She explained that transparency also matters – the aim is not to falsely advertise something. In Vitoria-Gasteiz, part of this transparency included data and evidence-sharing. The location of parking to be removed in the city was informed by a GIS layer that calculated parking supply and demand, showing where in the city there was an over-supply of parking. This evidence was used with key stakeholders and the public to explain and provide justification. In Jerusalem, public awareness was initially focused on ensuring that there was recognition of the problems related to car-dominance and pollution: “you can’t get people to solve a problem if people don’t see it”, Nimrod explained. Their public campaign – including TV advertisements – used positive and optimistic language and imagery and they monitored effectiveness with subsequent surveys. Translation of messages into different languages also made more achievable their priority to communicate effectively with different ethnic groups in the city.

In Padova, public awareness was ensured by a whole combination of approaches, including online meetings, face-to-face events, door-to-door leaflet dissemination. Similarly, in Bielefeld, there was intensive dialogue with citizens and a website was set up. What struck me most, however, was Olaf Lewald’s point that it is important to emphasise that the final decision is made by elected officials, not by the public, even if they are consulted on. This mirrors what I think has been a key lesson from the LTN consultation process in Greater London. Some resentment has been expressed from members of the public that despite respondents in some consultations being disproportionately ‘against’ rather than ‘for’ LTNs, some councils have implemented them anyway. As well as communicating more effectively that respondents often do not constitute a representative sample of the local population, local authorities might repeatedly emphasise that consultation does not equate to a referendum.

A final key aspect of public awareness that universally emerged was signage. Samantha Tharne explained that in the City of London (as in the UK), there is standardisation of signage to ensure consistency. However, she admitted that people still do not understand the signs. Indeed, more anecdotally, I have witnessed the difficulties that my own local authority has had in creating adequate signage, in keeping with standardised forms, that informs drivers of the presence of a modal filter as part of a Low Traffic Neighbourhood. It is not uncommon to see drivers stopped in front of a modal filter trying to understand whether they can continue driving through or not, despite the universal signs being part of the Highway Code. In Helmond, uniformity in signage was critical for their implementation of an Intelligent Speed Assistance scheme (that alerts drivers and restricts speed) as it required the digital reading of signs to accurately determine speed limits.

UVAR tool

How can other cities make use of the experiences and key lessons from these projects? To answer this question, at the end of the conference, a new UVAR tool was revealed. This has been designed to help cities that are considering putting UVAR measures in place. Based on information that the user inputs regarding the scope, characteristics of the area, mobility services already in place and area objectives, it will recommend which UVAR building blocks (e.g. cycle lane, permit to travel, pedestrian priority street) should be prioritised, provide information about them and guidance for how to regulate vehicle access. The tool is available here.

[1] https://trimis.ec.europa.eu/event/reveal-final-conference-2022

- School Streets: ATA podcast 2024:2 - July 1, 2024

- Accessibility and Urban Design: ATA podcast 2024:1 - January 25, 2024

- Queering Cartographic Methods: ATA podcast 2023:4 - July 6, 2023